OSU report finds public funding helped boost available child care slots in Oregon since 2020

CORVALLIS, Ore. (KTVZ) — Available child care slots for young children in Oregon grew by almost 5% from March 2020 to December 2022, thanks in part to increased public funding for child care, a new report from Oregon State University found.

In total, OSU researchers tallied 71,153 child care slots for ages 0-5 in 2022, up from 67,981 in 2020. But there is still work to pursue to increase child care throughout the state, state officials say.

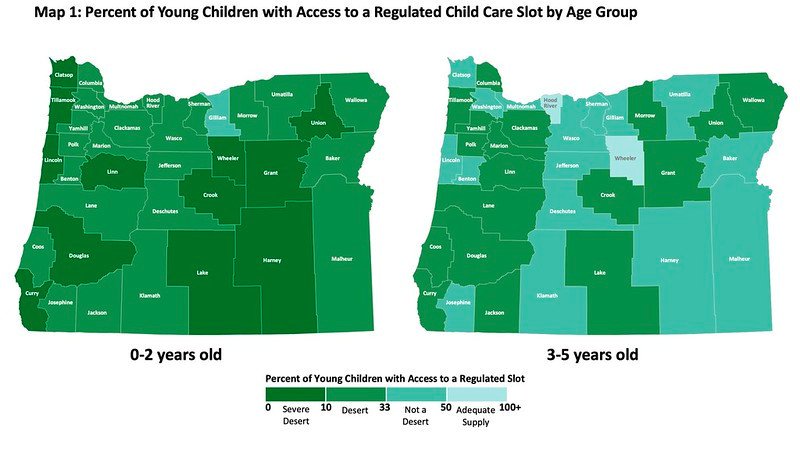

The increase lifted several counties out of “child care desert” status. A child care desert is an area where at least three children exist for every child care slot available. Severe deserts are defined as having at most one slot for every 10 children. For this report, researchers focused on regulated child care for infants and toddlers (ages 0-2) and preschool-aged children (ages 3-5).

Since March 2020, eight of Oregon’s 36 counties have moved out of desert status for preschool-aged kids, and another eight became less severe deserts for infants and toddlers. Though all Oregon counties except Gilliam County remain child care deserts for infants and toddlers, the number of publicly funded slots for this age group increased by 49%.

“We’re seeing a lot of those counties coming out of desert status because of the additional supply being developed from public funding,” said Michaella Sektnan, co-author on the report and senior faculty research assistant in OSU’s College of Public Health and Human Sciences. “Without that public funding, all except three counties would be child care deserts.”

Most of the public funding for child care in Oregon comes from the Early Learning Account created by the Student Success Act of 2019. One-time child care stabilization grants disbursed as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 helped private child care programs during the pandemic.

Between 2020 and 2022, available child care in Oregon increased by 1,789 infant-toddler child care slots and 1,383 preschool slots. In the same time frame, the number of publicly funded slots throughout the state increased by 4,214, split between 831 infant-toddler slots and 3,383 preschool slots. The public funds came primarily through Oregon Prenatal to Kindergarten, Preschool Promise and Baby Promise, which are state-administered programs that receive both state and federal dollars.

“The increased availability of child care slots since 2020 demonstrates the effectiveness of public investments and federal relief. It’s a good sign, but we can’t lose momentum,” said Alyssa Chatterjee, Early Learning System director at the state Early Learning Division. “We need to continue these investments in early learning and child care and communities agree.”

A recent survey conducted by the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center, a nonpartisan opinion research group, and the Children’s Institute, a family policy advocacy organization, found that 80% of Oregonians support increasing state funding to support child care needs, regardless of whether the respondents had children themselves.

Results also showed that 60% of Oregonians with young children spend 20% of their monthly income on child care, and 54% of Oregon employers say child care access is a challenge in hiring and retention.

“We see this as our call to action for the state to continue investing in early learning and child care programs,” Chatterjee said. “The long-term benefits of these investments are clear: stronger families, more equitable outcomes for Oregon children and a more robust economy.”

Public funding is currently making a bigger difference in rural counties than in more metropolitan counties, the report found. Overall, 52% of slots for children ages 0-5 in non-metropolitan counties are publicly funded, compared with 20% of slots in metropolitan counties. Only Deschutes, Multnomah and Washington counties would continue to not be deserts without publicly funded slots.

Researchers were pleasantly surprised to find that Oregon’s child care availability is actually in a better place now than pre-pandemic, Sektnan said.

“We know Oregon’s child care supply was not adequate before 2020, and the pandemic really highlighted that,” she said. “The current numbers speak to the efforts to restabilize and rebuild child care, but there is still important work to do.”

The report did not look at the specific factors affecting access to child care beyond general availability. Cost, schedules, transportation distances, culture and disability accommodations all affect whether families can actually benefit from the child care available in their area, Sektnan said.

The Early Learning Division, which will soon become the Department of Early Learning and Care, is currently working to increase availability and improve access by reducing licensing barriers, aligning program administration and reporting requirements, coordinating enrollment and making sure families are aware of the services available to them, Chatterjee said.

The report drew its data from multiple programs administered by the state’s Early Learning Division, including Oregon Prenatal to Kindergarten, Preschool Promise and Baby Promise. Researchers also included numbers from federal Head Start/Early Head Start, tribal Head Start, and Migrant and Seasonal Head Start programs. On the private side, data came from Find Child Care Oregon, which is administered by Child Care Resource and Referral agencies.