OSU veterinary lab partners with ODFW to boost testing for chronic wasting disease in deer

CORVALLIS, Ore. (KTVZ) — Faster and more widespread testing for chronic wasting disease in deer is now possible, due to a new partnership between the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University’s Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Chronic wasting disease is spread through animals’ waste and saliva, and infected animals can be contagious for months or years before showing symptoms. It is incurable and affects members of the cervidae family: deer, elk and moose.

The disease has not been detected in Oregon yet, but it has been found in deer just a few miles east of the border in Idaho, so Oregon wildlife officials say it’s only a matter of time and they want hunters to be aware.

To prepare for the disease’s arrival, the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory received a one-year grant to enable testing for chronic wasting disease in Oregon, rather than sending samples out of state to other national animal laboratories, which officials say can lead to long wait times.

Currently, the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory does not have the capacity to test for prions, the infectious proteins that cause the disease by altering the way proteins are folded in cells within the animal’s central nervous system.

“We’re going to have to acquire the equipment and the expertise to test for these prions. It’s going to be a challenge for us, but that’s what we’re here for,” said Kurt Williams, director of the laboratory at OSU. “I think it’s super important for the state of Oregon and all of us interested in the outdoors. For both hunters and non-hunters — this is something we ought to be doing here in Oregon.”

There is no evidence that the disease affects humans or spreads to livestock, Williams said, so at this point, the concern is for the health of the deer, elk and moose populations in the state. Chronic wasting disease is a “spongiform encephalopathic” disease, akin to mad cow in cattle and Creutzfeldt-Jakob in humans, named for the holes it causes within an animal’s brain. It is uniformly fatal and there is no vaccine. Infected animals lose their ability to eat and find proper nutrition, so they gradually waste away.

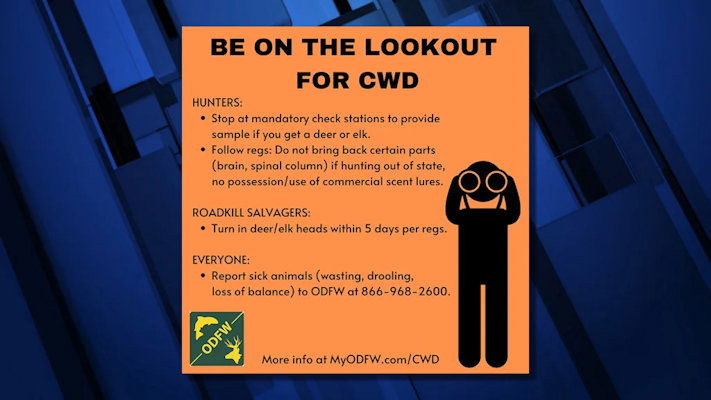

Most of the grant is focused on fieldwork, which includes testing more deceased animals, as well as outreach and education among hunters in the state, said Colin Gillin, state wildlife veterinarian with the Department of Fish and Wildlife. Trained biologists will collect samples of lymph nodes and brain stem, where prions are located in infected animals.

As soon as the first case is detected in Oregon, Gillin said the state will likely hold an emergency hunting season within a defined area around where the infected animal was found to reduce the number of infected animals and limit the spread of the disease.

“We’ll remove a statistically significant number of animals that are susceptible so we can get a high enough sample size to figure out the real percentage of animals that have the disease,” Gillin said. “The goal is to reduce the density such that the nose-to-nose contact of deer in that area will be a lot less.”

The department will also work to identify the area where infected animals are located and mitigate disease spread through management methods like carcass disposal and carcass movement restrictions.

The grant also funds a new online reporting system, where hunters who have killed deer or elk and had the carcass sampled by the Department of Fish and Wildlife can track their results online via QR codes. While there isn’t evidence the disease affects humans, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention do not recommend eating the meat of infected animals. The department will collect and safely dispose of carcasses that tested positive.

Previous research and modeling based on highly infected herds in Wyoming has shown that when infection prevalence gets to 19-20%, the disease may start to affect the animal populations long-term, Gillin said.

“Increased capacity and surveillance, decreased turnaround time reporting test results to hunters using OSU testing, and increasing education and outreach will help us catch the disease early so we can implement management actions to the benefit of Oregon’s wildlife and public,” he said.