The life and death of Tupac Shakur

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

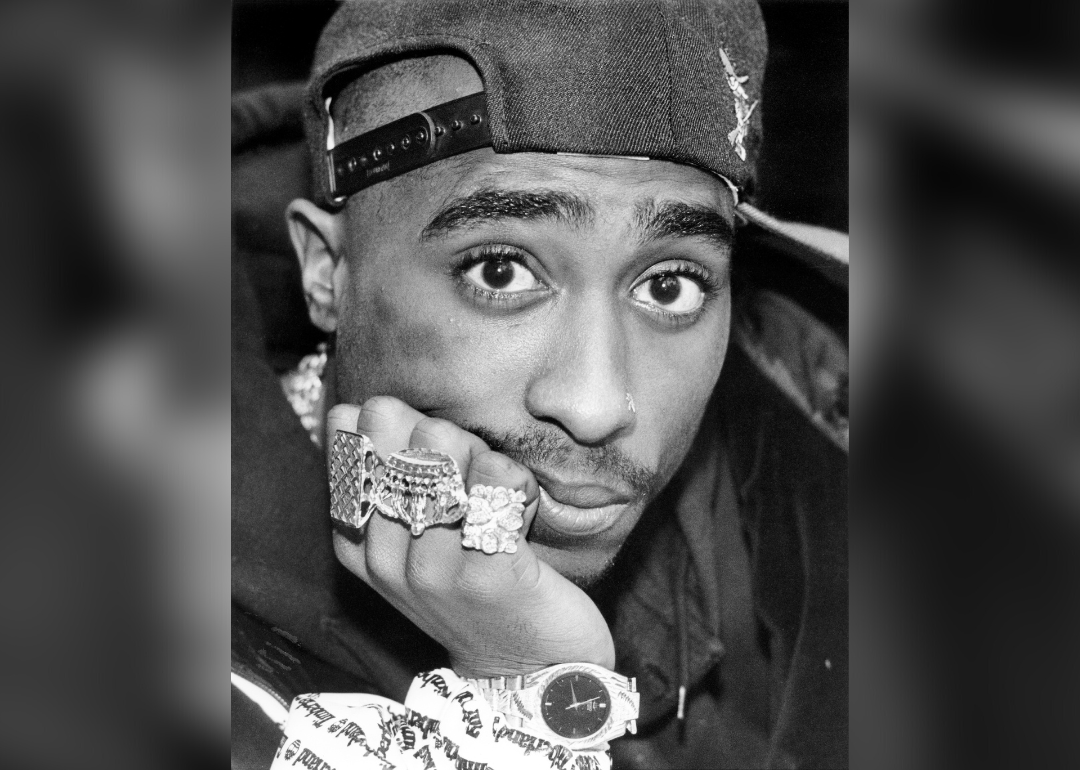

The life and death of Tupac Shakur

Tupac Shakur performs onstage.

While 2023 marks the 27th anniversary of Tupac Shakur’s death, for many, it feels like only yesterday. In a music career that would only last five years and three studio albums before his killing, the man, myth, and antihero left an indelible impression on hip-hop, the music industry, and the world. His words and philosophies are even taught at prestigious universities, including Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley.

The message of his music has managed to sell more than 75 million albums, making him one of the bestselling artists of all time. His likeness is captured on T-shirts, posters, and any manner of merchandise you can think of, further immortalizing him in pop culture iconography. No matter how you feel about rap, Tupac’s legacy goes far beyond music.

Born to a mother who was also a Black Panther and raised amid the wreckage of the revolution, Tupac played many roles throughout his life—son, brother, friend, protector, revolutionary, antagonist, and hero. From becoming the first solo rapper inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to earning a posthumous star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in June 2023, he broke barriers and earned accolades in every realm he entered. On paper, it seemed like he could have had it all.

In honor of Tupac’s enduring impact, Stacker looked at the life and death of the hip-hop legend. Using various sources, including interviews captured in the Hulu biography “Dear Mama,” court documents, first-person accounts, and numerous other sources, we bring you the legacy the rapper-actor left behind.

![]()

Gary Reyes/Bay Area News via Getty Images

Tupac was conceived amid a political revolution

Tupac Shakur poses for a portrait.

On April 2, 1969, police arrested members of the Panther 21—composed of 19 men and two women, including Afeni Shakur—under accusations of conspiracy to commit violence against various locations in New York City after an undercover police officer infiltrated the Panthers through Cointelpro. If found guilty, Afeni would face 350 years in prison.

While pregnant, Afeni was placed on bond, rearrested, rereleased on bond, and infamously defended herself against the state. She was eventually released and acquitted on all charges; a month later, she gave birth to a son.

David Fenton // Getty Images

The birth of a legend

Afeni Shakur holds a camera as she attends a session of the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention.

Tupac was born Lesane Parish Crooks on June 16, 1971, in East Harlem, New York, to Afeni, an influential leader in the Black Panther Party. He was born one month after his mother, who was accused of participating in bombing attacks on two New York City police stations, was acquitted and released after serving as her own defense attorney.

David Fenton // Getty Images

The backstory of his name change as a baby

Dhoruba Bin Wahad, Afeni Shakur, and Jamal Joseph at rally in support of the Panther 21.

Afeni changed her baby’s name from Lesane Parish Crooks about one year after his birth to Tupac Amaru Shakur. The name Tupac Amaru is layered with meaning, both in the etymology of the world and the story of the men who held the name before him.

Tupac Amaru, meaning “shining serpent” in Quechua, was a name ascribed to the last Indigenous Inca chief to fight back against the Spanish colonization of modern-day Peru. According to many sources, Afeni reportedly chose the name for her son because she wanted him to share the name of the “revolutionary, Indigenous people of the world.”

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

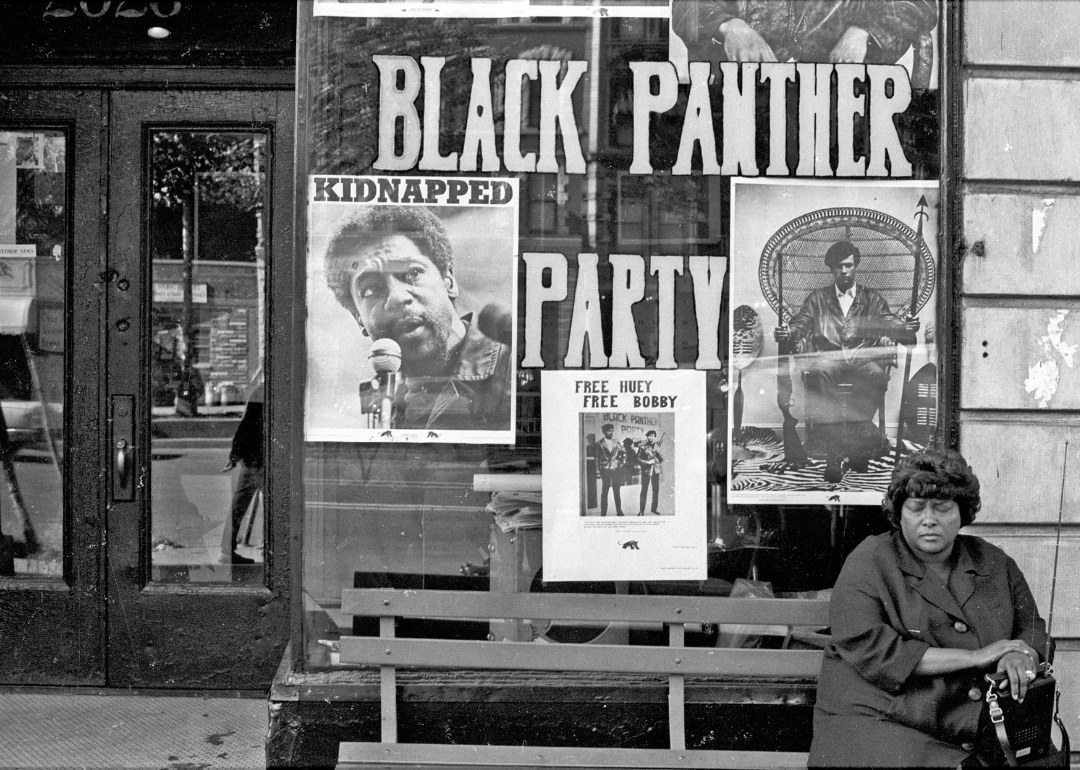

Tupac spent most of his early life in New York

A woman sits on a bench outside the Black Panther office in Harlem.

Despite Tupac heavily representing California and all things West Coast, he was born and spent the first 13 years of his life in different boroughs of New York City, primarily Harlem and the Bronx. He often remarked later in life that his family left New York and ended up in Baltimore in his teen years because of his mother’s choices related to her drug use. “My mom was a crack addict,” Tupac says in the trailer for Hulu’s “Dear Mama.” “I ended up in Baltimore with no lights on welfare.”

Mitchell Gerber/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

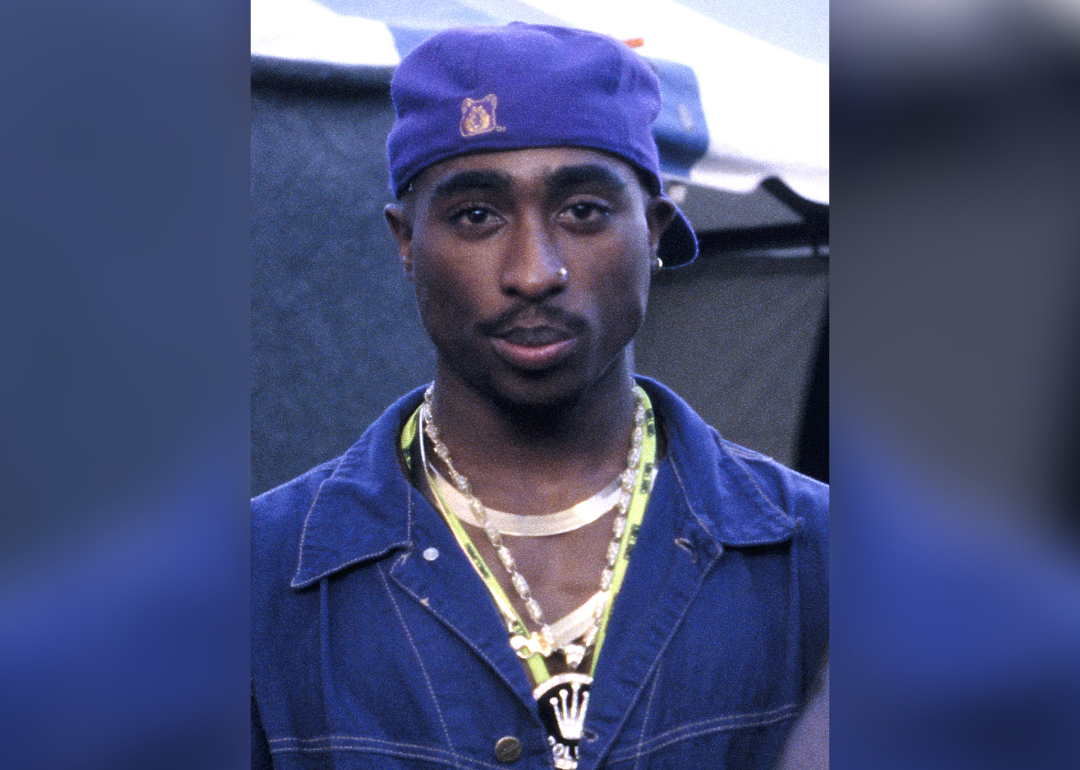

Tupac’s strained relationship with his mother

Tupac Shakur poses for a portrait.

Both Tupac and Afeni were very open about their strained relationship, especially during his teen years in Baltimore. After her time in the Black Panthers, the trauma of confinement, police oppression, and violence she suffered, Afeni turned to drugs as a method of coping.

As they both grew and Afeni got clean, they appeared to restore their relationship before his death. His song “Dear Mama” became one of his most celebrated: It went triple platinum and was inducted into the Library of Congress Recording Registry in 2010.

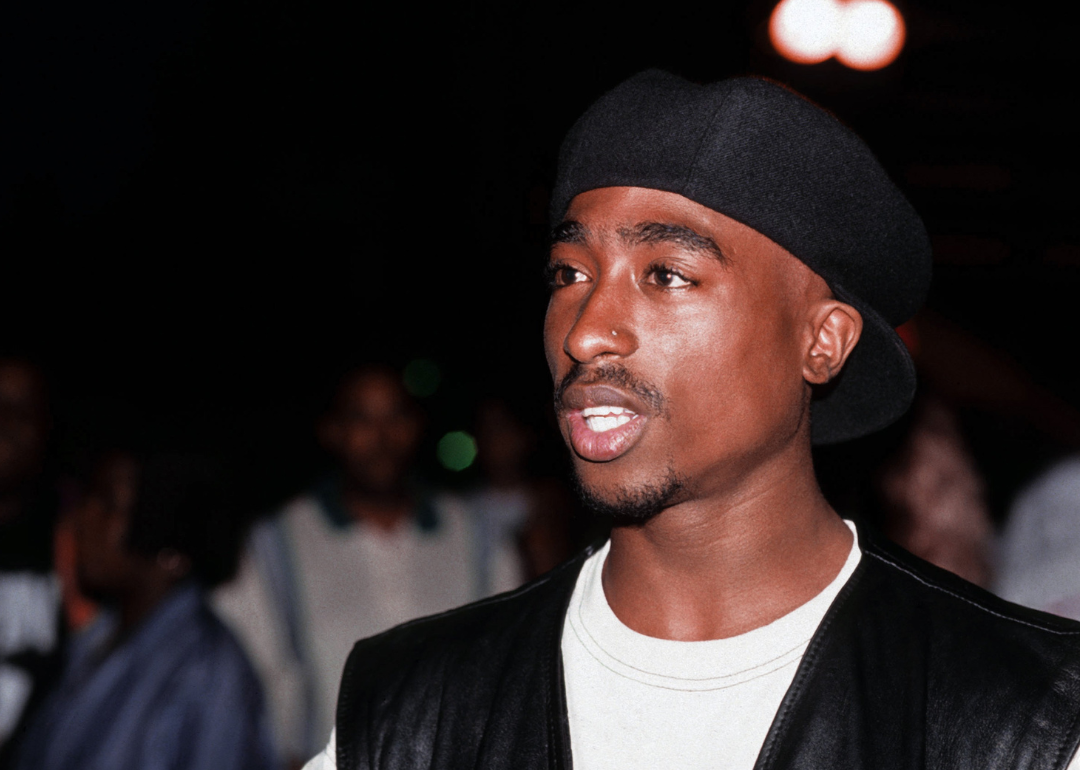

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

Tupac’s stepfather, former political prisoner Dr. Mutulu Shakur

Tupac Shakur performs onstage.

When Tupac was 4, his mother married Dr. Mutulu Shakur, a former Black Liberation Army member and the stepbrother to her first husband, Lumumba Shakur. Mutulu was later convicted of assisting in the prison escape of Assata Shakur from a New Jersey penitentiary in 1979, as well as of an attempted robbery of a Brink’s armored truck in which two police officers were killed. Mutulu was also the father to Tupac’s half-sister, Sekyiwa. After spending 35 years imprisoned, Mutulu was released on parole in January 2023.

Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

Discovered his love of performing in Baltimore

Tupac Shakur poses for a portrait.

Not long after moving from New York to Baltimore at age 13, Tupac turned to performing. Though he originally went to Dunbar High School, he transferred to the Baltimore School of the Arts soon after; there, Tupac majored in theater while also studying ballet and jazz. While it seemed Tupac enjoyed his time at BSA, Afeni’s difficulties in maintaining consistent income—coupled with her fears that her children would fall into the violence of the city—caused them to uproot to California when he was 17.

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

Claimed the Bay Area as his first California love

Tupac Shakur performs onstage.

With few options available to her, Afeni sent Tupac and Sekyiwa to Marin City, California, to live with Assata, a friend from the Black Panthers. A suburb of Oakland and neighboring San Francisco, Marin City is an unincorporated community attached to Marin County. While Marin County was and still is one of the most affluent, predominantly white communities in the United States, Marin City—where Tupac and his family found residence—was the polar opposite.

During the years Tupac lived there, the unemployment rate in Marin City was nearly 10 times what it was in Marin County, with much of the population living below the poverty line. After saving money for a ticket to move herself, Afeni would later join her children in Marin City.

Tim Mosenfelder/ImageDirect // Getty Images

First interview at 17

Tupac Shakur backstage.

Tupac’s time in Marin City was difficult. Assata lived in a low-income community known for its high rate of violent crimes. In an attempt to give him as diverse an education as possible, she enrolled Tupac in Tamalpais High School—still widely considered one of the best schools in the area—which offered him a completely different environment than he would find at home. At Tamalpais, Tupac gave one of his first on-record interviews at age 17.

Clarence Gatson/Gado // Getty Images

Discovers his musical talents in Oakland

Flavor Flav and Tupac Shakur backstage at 1989 American Music Awards.

Not long after graduating high school, Tupac and his family found themselves in Oakland, California, moving into a tiny apartment in a small housing community that has since gained landmark status in the minds of many as a site any music fan should visit if they are in the area.

While living in Oakland, the rapper took a writing workshop from Leila Steinberg. Though less than a decade his senior, Steinberg would become an important mentor in his life and later serve as his first manager. Steinberg introduced Tupac to Atron Gregory, who facilitated another famous introduction that opened the door for Tupac’s big break.

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

The Bay Area embraced Tupac by way of Shock G

Tupac performing with Digital Underground.

Atron Gregory was already making a name for himself in the hip-hop world as the manager of the hip-hop crew Digital Underground, who had already gained heavy play on the airwaves thanks to their single “The Humpty Dance.” Impressed by his first meeting with Tupac, Gregory introduced him to Gregory Jacobs (aka Shock G), the leader of Digital Underground.

Shock took an immediate liking to Tupac and, realizing he was hungry for work, agreed to take Tupac on tour with them as a roadie. It wasn’t long before Tupac proved his worth, and Shock gave him his debut with a verse on the single “Same Song.” Shock continued to be a friend and mentor to Tupac through most of his career before the aspiring rapper’s Death Row Records days.

Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

Tupac almost gave up music for politics

Tupac Shakur poses for a portrait.

Though Tupac loved all manner of performing from an early age, he was still heavily political throughout his life. His mother instilled in him at an early age a sense of responsibility and duty to protect and care for his people. During his time with Digital Underground, Tupac considered stepping away from music entirely.

Tupac considered becoming the national chairman for the New Afrikan Panther Party, an offshoot of the original Black Panther Party composed of many panther cubs who had been led and taught by the generation before them. In Hulu’s “Dear Mama,” his former manager, Atron Gregory, recalled Tupac would remain with the NAPP unless “he got a record deal quick.”

By August 1991, that declaration became a reality as Tupac became “2Pac” and signed with Interscope Records.

Gary Reyes/Bay Area News via Getty Images

Tupac experienced police brutality months after inking record deal

Tupac Shakur poses for a portrait.

While Tupac found quick success in the music industry, his manager, Atron Gregory, did his best to ensure the rapper was taking precautions with his money. In the Hulu documentary “Dear Mama,” Gregory recalled the jaywalking incident that led to Tupac’s violent beating at the hands of two white Oakland police officers.

“I made him open a bank account. The police saw him walking across the street to go get some money out of the bank,” Gregory explained in the documentary. The officers then accosted him for jaywalking, a crime that—up until Jan. 1, 2023—was still illegal in the state of California.

Tupac alleged the officers harassed him because of his name, and when he talked back, he was thrown to the ground, placed in a sleeper hold, and beaten unconscious. Following the incident, Tupac sued the Oakland Police Department for $10 million.

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

1991, the year of the ‘2Pacalypse’

Tupac Shakur at event.

Less than three months after the ink dried on the recording contract between Tupac, TNT Records, and Interscope Records, the lyricist released his debut album, “2Pacalypse Now.” The album came on the heels of the lead single, “Trapped,” a raw and reflective song that laid bare the wounds of police brutality, racism, and oppression against the Black community.

Already a powerful introduction to the world, the assertive messaging of the follow-up single to “Trapped” would solidify Tupac in the lexicon of music legends.

Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

‘Brenda’s Got a Baby’

Tupac Shakur performs onstage.

When “Brenda’s Got a Baby” was released in 1991, the song’s message was shocking, intense, and profoundly sad—made even more so because of its real-life story.

The song told a sordid tale of a 12-year-old girl named Brenda, who comes from a broken home with an absentee mother and father struggling with drug addiction. After an adult cousin molests and impregnates her, Brenda hides the pregnancy from her family. In the song, she ends up having her baby in a public bathroom before abandoning the child in a dumpster. While the fictionalized track culminates in a violent end to Brenda’s life, the real-life version is just as painful.

Through the song, Tupac addressed many issues—teen pregnancy, the unspoken realities of incest in Black and brown communities, and the lack of resources available to impoverished people in Brenda’s situation.

Paramount // Getty Images

The rapper’s first film role

Khalil Kain, Omar Epps, Tupac Shakur, and Jermaine Hopkins in a scene from the film Juice.

Though Tupac had a passion and talent for making music, his first love of acting never left him, and by 1991, he landed his first major role in the classic film “Juice.” Tupac morphed into his character, Bishop, a rebellious teen seduced by the streets of Harlem. His breakthrough acting performance was largely lauded as a success, and Tupac went on to play iconic film roles, including Lucky in “Poetic Justice” and Spoon in “Gridlock’d.”

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

Legal troubles

Tupac Shakur poses for a photo backstage.

Not long after the release of his first album and feature film debut, Tupac fell under heavy scrutiny by both the media and the justice system—especially after the incident involving Ronald Ray Howard. Howard was riding in a stolen car in his neighborhood when Texas State Trooper Bill Davidson pulled him over. Howard pulled a weapon on Davidson, shooting him in the neck before fleeing. Davidson died in the hospital shortly after Howard confessed.

When Ronald was pulled over, he was playing a dubbed copy of “2Pacalypse Now,” featuring the song “Soulja’s Story.” Prosecutors claimed the song’s narrative of two brothers who die in a shootout with police inspired the teen to shoot Davidson that day. The incident prompted then-Vice President Dan Quayle to attempt to remove Tupac’s albums from stores, though he was unsuccessful.

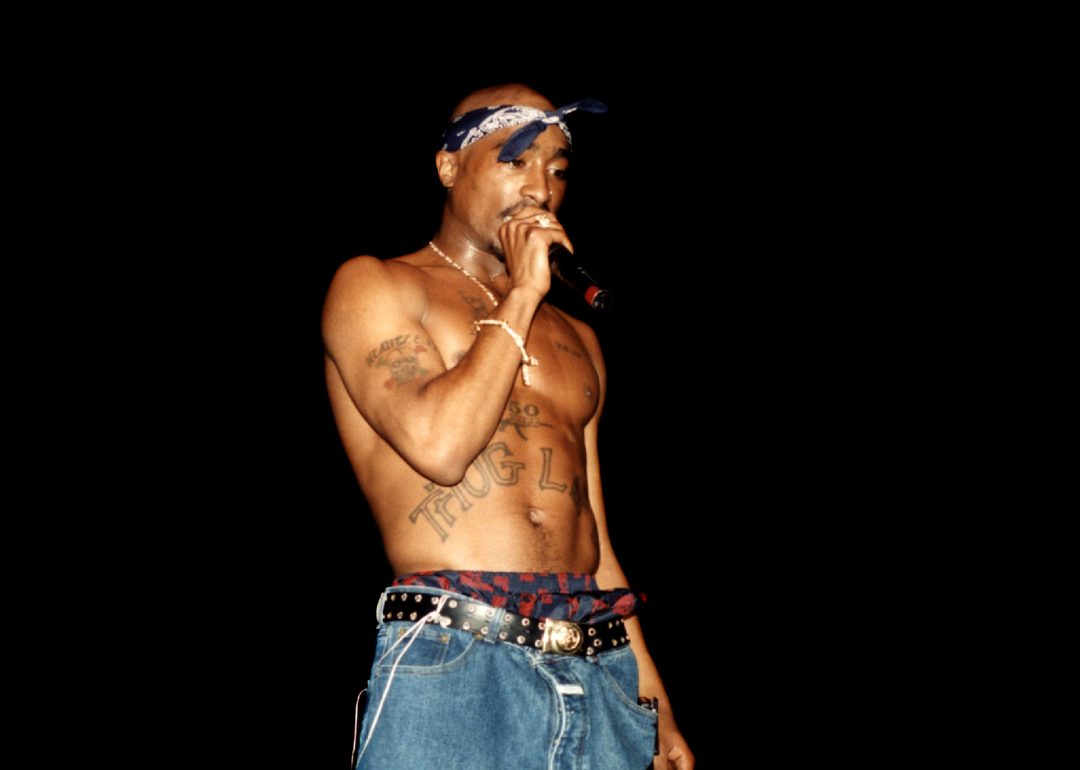

Raymond Boyd // Getty Images

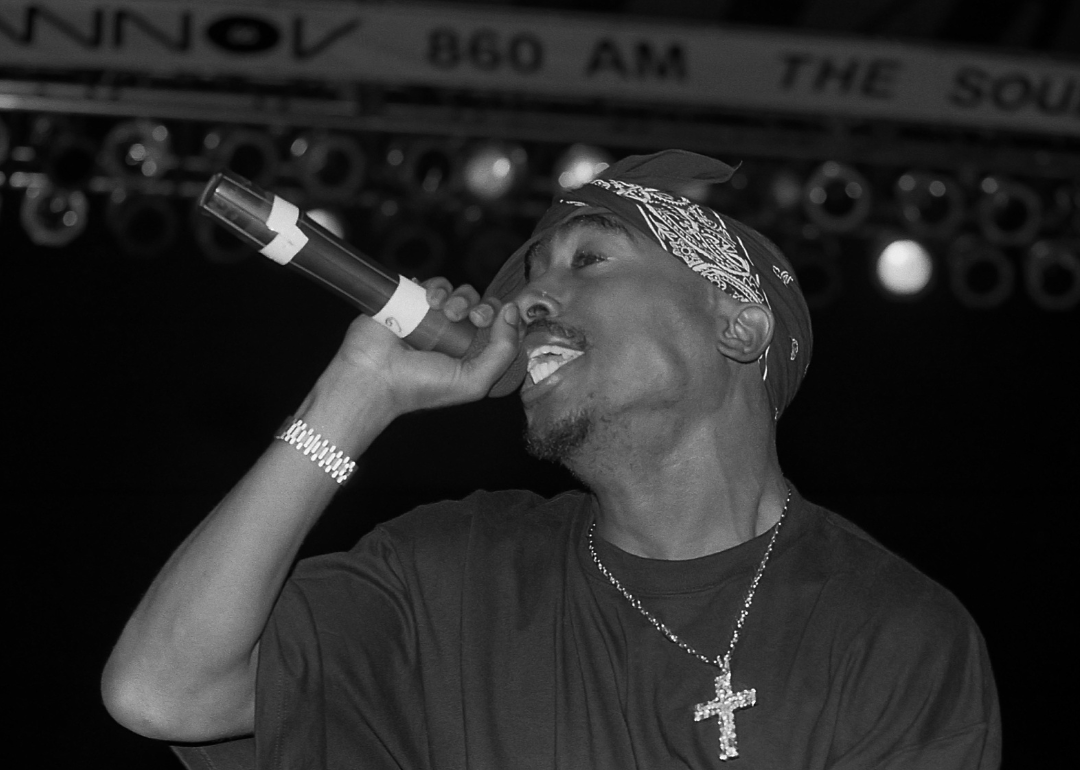

THUG LIFE

Tupac Shakur performs at the Regal Theater.

Tupac adopted a mantra in life he continued to scream until his dying day: “THUG LIFE.” The rapper even went as far as tattooing the phrase across his torso.

While many associated the concept with the literal, violent meaning of the word “thug,” the phrase was an acronym for “The Hate U Give Little Infants F—- Everybody.” Tupac contended that no matter what you did as a Black person in the United States, systemic oppression says Black people will always be viewed as thugs. In his own way, it seemed the phrase was his reclamation of the meaning.

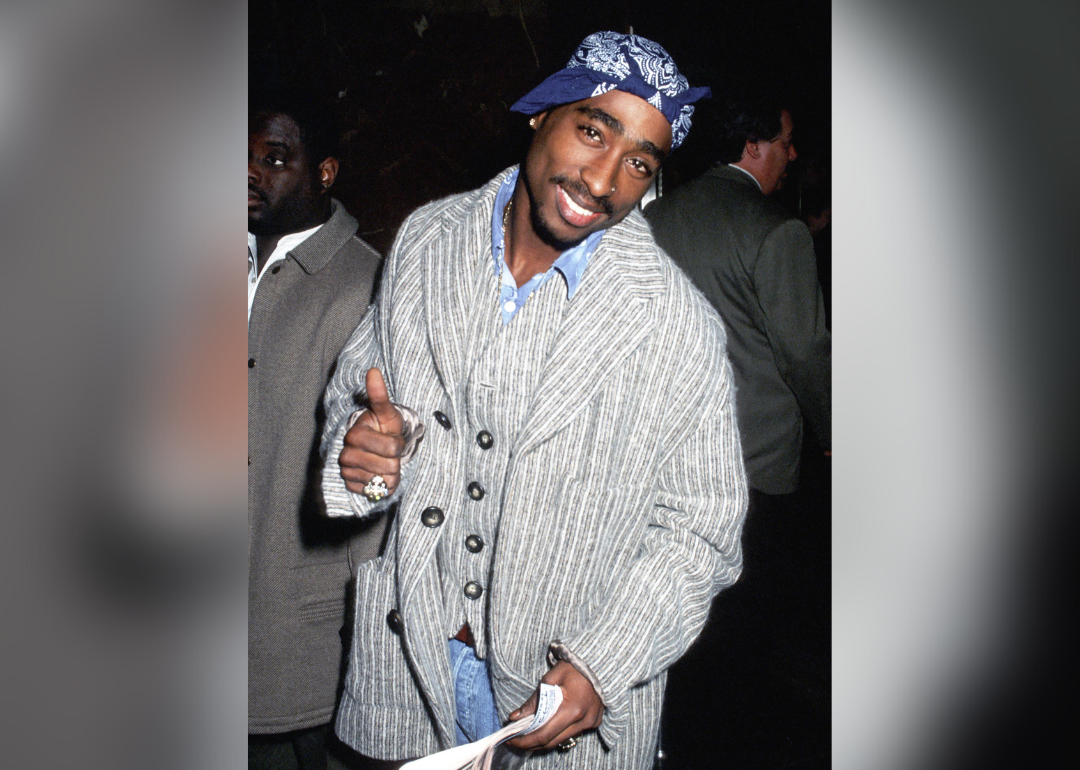

Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

Riding the controversial wave, Tupac’s second album

Tupac Shakur at event.

For better or worse, the world was talking about Tupac, and Interscope Records rode the wave by releasing his second studio album, which also contained a cleverly coded acronym. While his first album certainly made the artist a household name, his second became instantly successful, debuting at #24 on the Billboard Hot 200 chart and featuring such hits as “I Get Around,” “Holler If Ya Hear Me,” and “Keep Ya Head Up.”

While many songs resonated with hip-hop fans, “Keep Ya Head Up” found its way into the hearts of listeners with its message of empowerment toward women—Black women, especially. “Keep Ya Head Up” was also the song whose lyrics would come back to haunt Tupac months later.

mark peterson/Corbis via Getty Images

The Atlanta incident

Tupac Shakur on the set of Above the Rim in Harlem.

Tupac was in Atlanta for a performance at Clark Atlanta University in October 1993 when a situation occurred that forced the rapper to shoot at two undercover police officers in self-defense. According to his testimony, considered the most credible version of the events, Tupac was leaving the school and returning to his hotel when he and his friends witnessed an altercation between two intoxicated white men harassing a Black motorist.

Witnesses said Tupac exited a car to intervene when the men, who turned out to be undercover police officers, brandished a weapon. Seeing this, the rapper retrieved his own weapon and fired. The judge ruled Tupac had acted in self-defense.

James Leynse/Corbis via Getty Images

Arrested on sexual assault charges

Tupac Shakur leaves a New York City courtroom.

On Nov. 18, 1993, a mere 17 days after the shooting incident in Atlanta, Tupac was arrested on various sexual assault charges, including first-degree sexual assault and sodomy, along with illegal possession of firearms.

The victim, Ayanna Jackson, said she’d gone to visit the rapper at his hotel while he was on location filming “Above the Rim,” a film loosely based on the life of real-life gangster Jacques “Haitian Jack” Agnant, who was at the hotel with Tupac. Although she had gone to see Tupac that night, Jackson claimed things turned ugly when the artist allegedly offered her to his friends.

He went on trial for the incident in 1994.

James Leynse/Corbis via Getty Images

Tupac shot 5 times at Quad Recording Studios in New York

Tupac Shakur leaves a New York City courtroom.

By this time, according to Afeni and those close to Tupac, the musician became hyperaware of his surroundings. He struggled to believe the string of recent incidents weren’t somehow related.

On Nov. 30, 1994, while awaiting the verdict on his sexual assault case, Tupac was at Quad Recording Studios, a well-known spot in New York for the top rappers and producers to visit while in the city.

The Washington Post reported it was there that multiple gunmen ambushed Tupac in the lobby in an attempt to rob him. He was shot five times—twice in the head, once in the groin, once in the left arm, and once in the thigh—after refusing to submit to the gunmen’s demands, according to witnesses. The next day, he was convicted of first-degree sexual assault.

While Tupac maintained his innocence up to his death, he was convicted of first-degree sexual abuse and received a sentence of 1.5 to 4.5 years in prison, specifically at Rikers Island.

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic // Getty Images

The Death (Row) sentence and Suge Knight

Tupac Shakur and Marion Suge Knight.

Despite the sexual assault conviction, Tupac was still considered a commodity in the music industry. Though his resources and funds had dwindled during the trial, there were still plenty of eyes on the prolific rapper with a troubled image. During his incarceration, Death Row Records CEO Suge Knight inked a three-album, $1.4 million contract with the rapper—exactly the amount of money Tupac needed to post bail and be released from Rikers.

It’s a move many have looked back on as the beginning of the end for the rapper.

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

Stirs East Coast-West Coast rivalry

Tupac Shakur New York State Department of Corrections mug shot.

Having already been paranoid following the events between 1993 and his release from Rikers, Tupac seemed fueled by the idea that there was now a rivalry between him, Notorious B.I.G, and Sean “Puffy Daddy” Combs.

The flames were further fueled by Knight, who had established himself as the protector of Tupac, whom he considered his “little brother.” Quincy Jones’ now-defunct Vibe magazine had also been accused of creating the rivalry to sell magazines. While no rivalry has ever been confirmed, it still seemed to play a role in Tupac’s violent end.

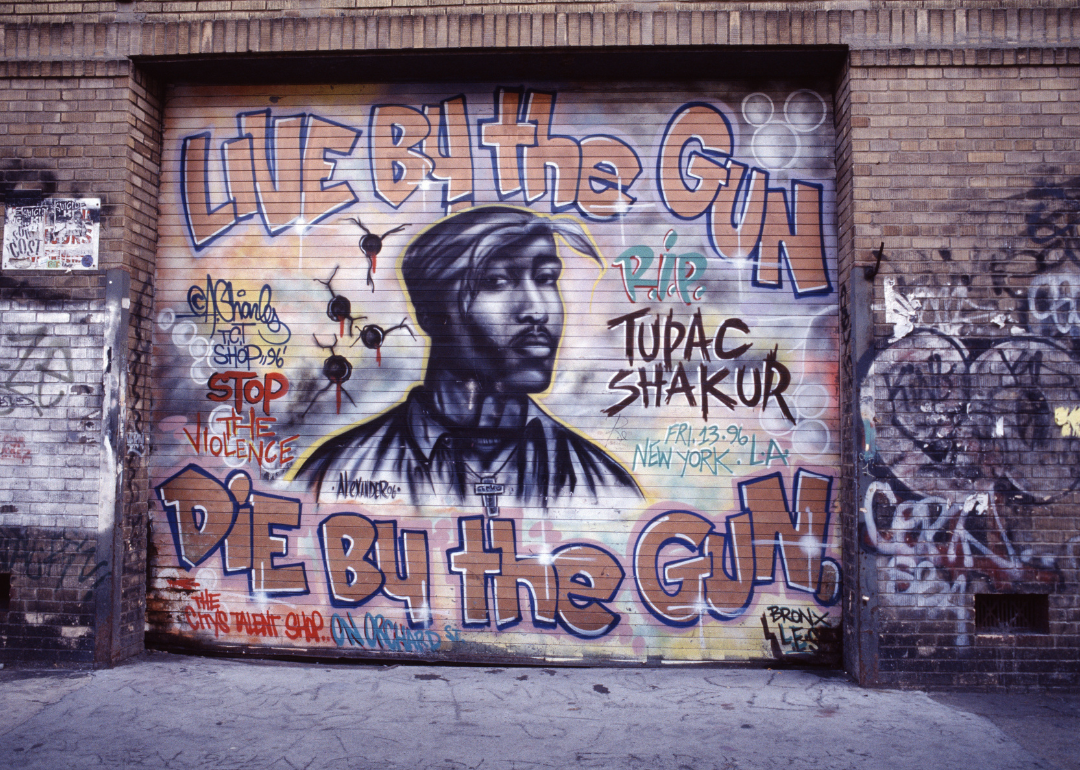

Rita Barros // Getty Images

Tupac killed at 25

Street mural ‘Live By the Gun, Die By the Gun’ by Andre Charles.

Tupac, Suge Knight, and their crew attended the Mike Tyson-Bruce Seldon fight at the MGM Grand on Sept. 7, 1996. After Tyson knocked out Seldon and the fight was called at 8:39 p.m., the group left and headed toward the lobby.

Security camera footage would later show the group getting into a violent altercation with Orlando Anderson, a well-known gang member who allegedly had placed a hit on someone within Knight’s crew. Spotting Anderson, Tupac allegedly initiated an altercation before dispersing as security arrived.

Less than three hours later, while driving down the Las Vegas Strip in a black BMW with Knight in the driver’s seat, the car was gunned down, leaving Tupac struck four times. Tupac was taken to the hospital and placed in a medically induced coma.

After several days in the hospital, on Sept. 13, 1996, the 25-year-old rapper succumbed to his gunshot wounds.

Story editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Paris Close.