The persistence of anti-Black hate crimes is an American tradition: What more than 30 years of federal data tells us

Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The persistence of anti-Black hate crimes is an American tradition: What more than 30 years of federal data tells us

Jacob Patterson, 11, is comforted as his mother speaks during a news conference about the mass shooting in Buffalo New York on. May 19, 2022.

Last September, Angel Pittman bought land in a small town 8 miles outside Salisbury, North Carolina, with plans to build a tiny home to live in and transform buses into mobile salons on her new property. Weeks later, the 21-year-old hairstylist returned to find her buses vandalized with anti-Black racial slurs. Her neighbor, a white man, sat outside his home, his gun on display, his yard brandishing Ku Klux Klan signs, Confederate flags, and swastikas. “Oh, yeah, they do that all the time,” Pittman, speaking to The Guardian, recalled deputies telling her of the scene. A sheriff’s captain in the county told the outlet the incident was not a hate crime.

Fearing for her safety, Pittman moved back to her hometown of Charlotte. Thousands have since rallied to help her recoup her losses, raising over $118,600 in donations.

Hate crimes are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as a “criminal offense which is motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender’s bias(es) against a person based on race, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender, and gender identity.” Rates of violence against marginalized individuals vary in frequency throughout the 30 years of documented reports from the FBI. Still, according to an annual report from the bureau, one thing remains constant: Black Americans are the most targeted demographic.

According to reports and surveys from the FBI and the Department of Justice, hate crimes have largely been connected to race or ethnicity. Within this sect of reported hate crimes, Black Americans carry most of the burden. With this in mind, Stacker analyzed data from the FBI’s annual Hate Crime Statistics report to chronicle how Black Americans are affected by hate crimes.

![]()

Stacker // Jared Beilby

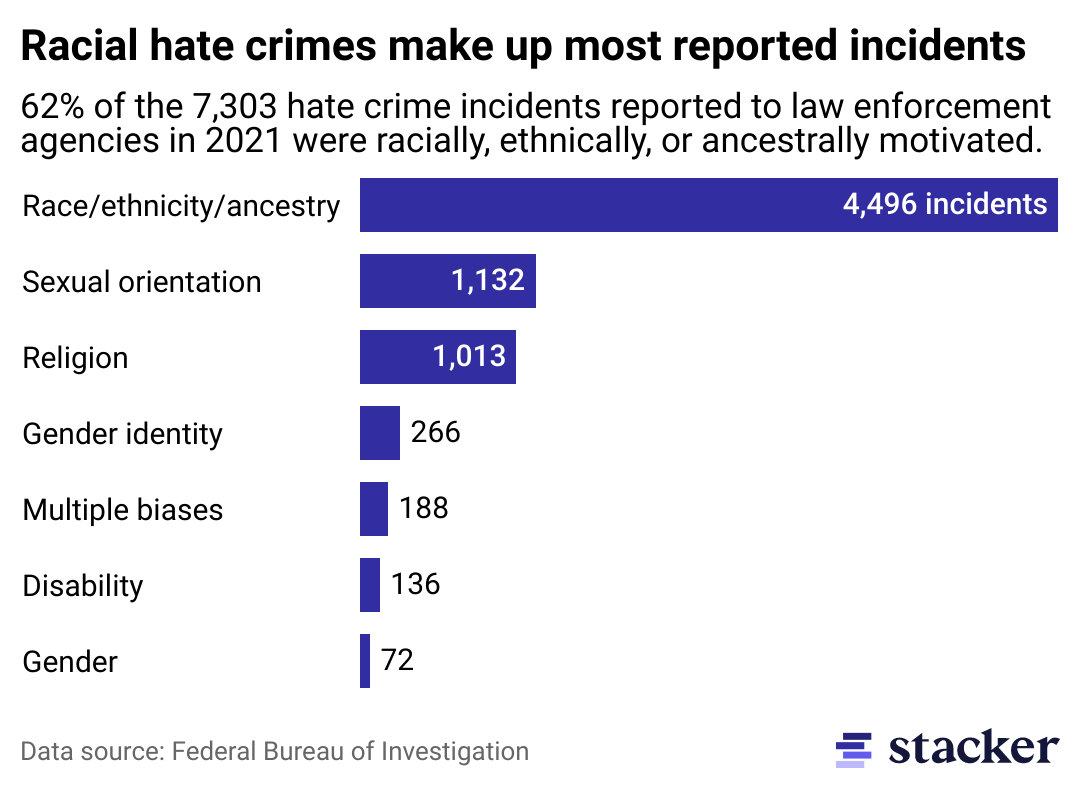

Over 60% of all reported hate crimes are racially motivated

Bar chart showing the number of US-based hate crimes in different bias categories for 2021.

Hate crimes reported in 2021, the latest available data, show motivation was most commonly linked to race or ethnicity, accounting for nearly 4,500 incidents. Sexual orientation and religion—with 1,132 and 1,013 incidents, respectively—were the second and third most common biases.

This graph indicates only a fraction of hate crimes in the United States. Getting a full picture is a complicated affair. As ProPublica explains, the FBI relies on local enforcement agencies to collect and submit hate crime data, but there are no clear regulations and processes in place to do so. The nonprofit’s investigation exposed communication breakdowns between local and federal agencies. Thousands of cases each year are lost in this broken system. These figures should then be at least taken as a means to determine trends and patterns.

One indication of the wide margin between reported and actual incidents lies in the discrepancy between the Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey and the FBI’s data. From 2005 and 2019, there were about 246,900 hate crime incidents self-reported by households annually. The FBI, however, only tallied 7,303 hate crimes in 2021—3% of that yearly average.

Stacker // Jared Beilby

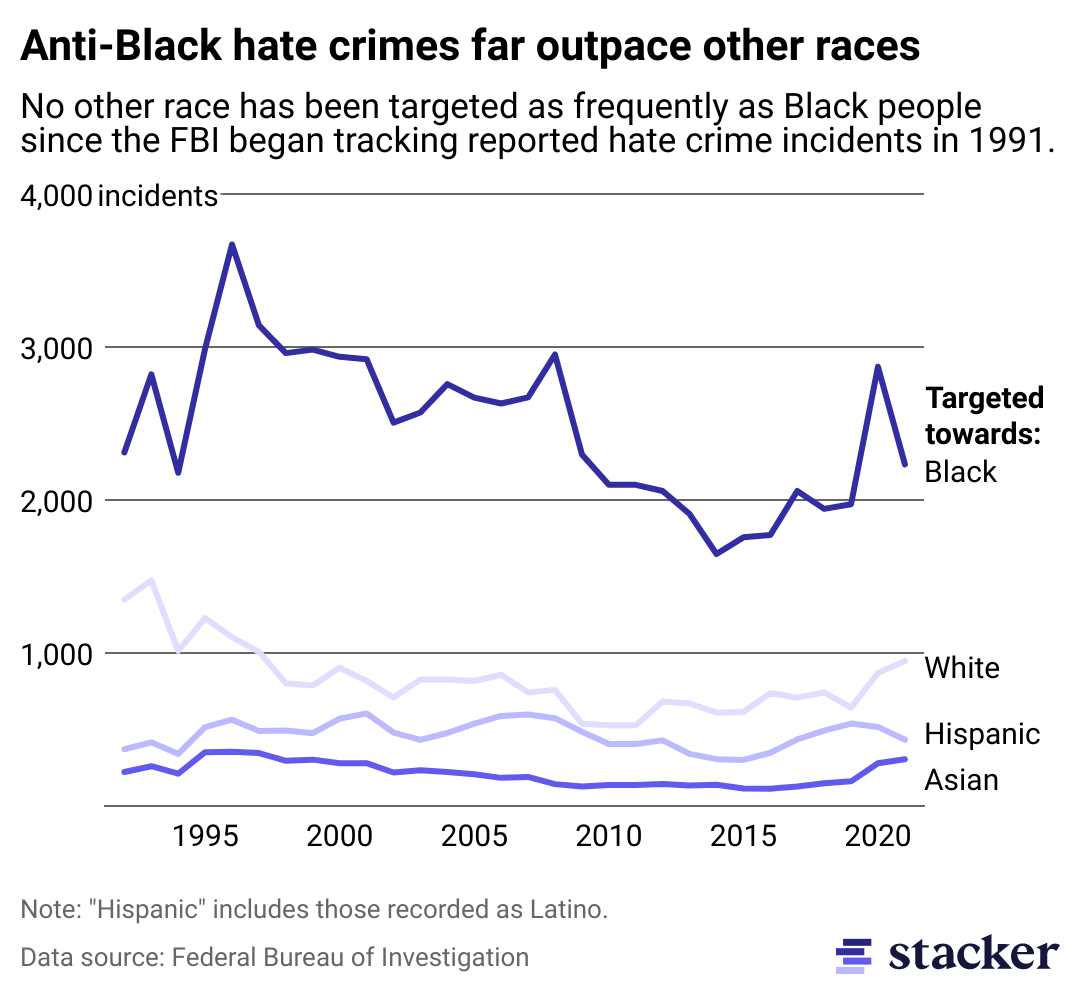

At least 1,500 anti-Black hate crimes have been reported every year since 1991

Line chart showing the number of hate crimes targeted toward different races over the past 30 years.

The FBI began tracking hate crimes in 1991. More than 4,500 race-based hate crimes are reported annually—and that number has only increased.

The numbers have varied over time. There were sharp upticks for hate crimes toward Black Americans shown in 1996, the year former President Bill Clinton signed a welfare reform bill into law, sparking discussions about its supposed beneficiaries; 2008, the year after the Southern Poverty Law Center noted a staggering growth of hate groups such as neo-Nazis, skinheads, KKK, and Black separatists (which the SPLC has since collapsed to avoid drawing a false equivalency to white supremacist extremism); and 2020, when the country grappled with social upheavals amid the COVID-19 pandemic. That year, Black Americans accounted for 31% of racially motivated hate crimes reported in 2021, per FBI data.

Libby March for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Complete data based on official hate crime reporting is limited

Two mourners visit a memorial in remembrance of the Buffalo mass shooting.

Reliable hate crime data is limited, in part due to local agencies’ reporting protocols and specific reporting criteria and definitions. Disparities in reporting are shown between local and federal agencies, with some even claiming to have no hate crimes in 2016.

Additionally, according to the FBI, the report collected in 2021 is the first to be compiled with data completely from the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which aims to improve the “overall quality of crime data collected by law enforcement” by capturing comprehensive information on each single crime incident as well as separate offenses within the same incident. During this transition to this system, some individual agencies and states failed to switch over to the new system in time, resulting in a lack of data for 2021. Because of this, there is a noticeable decline in reports between 2020 and 2021.

Stacker // Jared Beilby

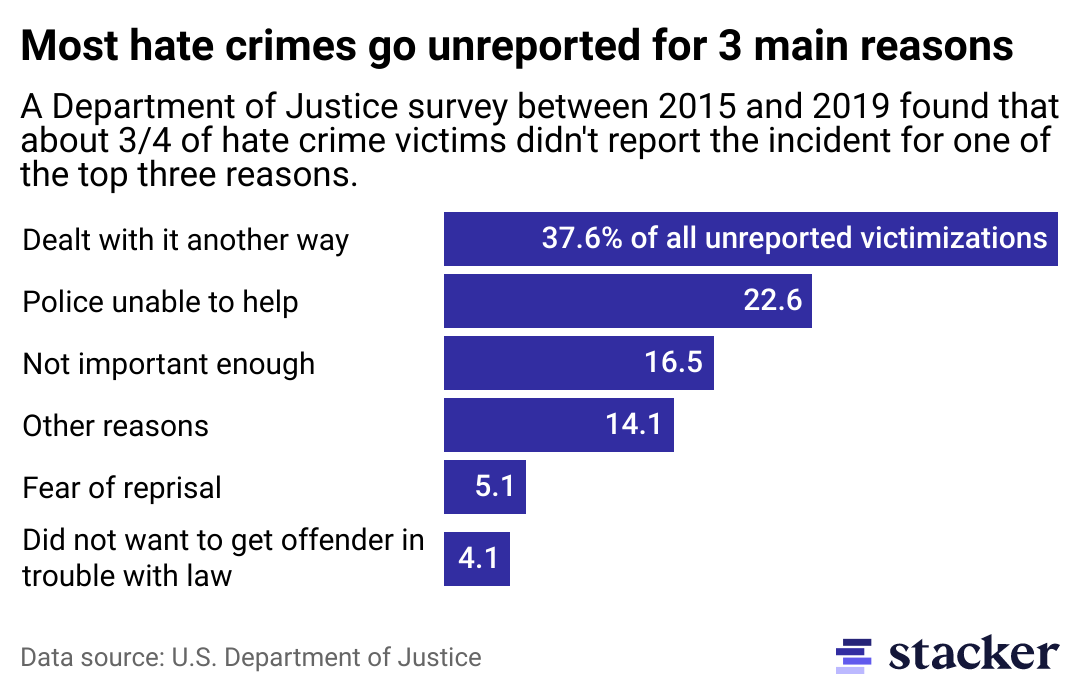

There are 3 main reasons why hate crimes go unreported

Bar chart showing the reasons why hate crimes go unreported.

On June 17, 2015, a group of Black churchgoers were attending Bible study at a historic Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, when white supremacist Dylann Roof—who had even sat in on the session—drew out a handgun and shot and killed nine of them. He was later convicted of 33 hate crimes and murder charges.

Roof’s outspokenness about his anti-Black views—through his public website and writings from jail—and the aftermath of the massacre stirred conversations among federal lawmakers about the proposal of an anti-Black-specific hate crime bill shortly after. However, it has yet to move forward.

In 2021, Congress passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act to specifically address anti-Asian hate crimes—and rightfully so—after the increase in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. In 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act sought to prosecute hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender. No such bill exists regarding anti-Black hate crimes. In fact, the U.S. had no anti-lynching legislation until 2022, more than 100 years after the country’s only Black member of Congress attempted to pass one in 1900.

Almost seven years after the Charleston shooting, on May 14, 2022, a white 18-year-old man named Payton Gendron traveled 3.5 hours from his hometown to Buffalo, New York, walked into a supermarket in a predominantly Black neighborhood armed with an AR-15-style rifle, and opened fire on 13 innocent shoppers, killing 10—all of whom were Black. Gendron received back-to-back life sentences without the possibility of parole for his racially motivated hate crimes.

The Buffalo tragedy hearkened back to the Charleston church massacre, reigniting demands for protections for Black Americans against such hate crimes—yet still to no avail.

Circumstances like these factor into the hesitation from victims regarding making official reports, ultimately contributing to the limitations of hate crime data.

In more than a third of cases (38%), victims surveyed said they dealt with the crime in another way rather than reporting it to the police. Almost a quarter (23%) of DOJ’s survey participants who did not report hate crimes also stated they believed police would not or could not do anything to help. Other reasons for not reporting fell under the category of “not important enough,” which includes victims who said it was a minor or unsuccessful crime, situations where the offender(s) was a child, or that insurance would not cover their losses.

Fear of retaliation from the offender was the third most common reason victims chose not to report.

Eugenio Marongiu // Shutterstock

Opportunity for nuanced conversation and data

Black lives matter movement protest sign.

With the FBI’s data set, a category of “multiple biases” exists, leaving room for additional data to show hate crimes involving Black Americans that also occupy other marginalized identities. This highlights the opportunity for explicit discussion around hate crimes that cross intersections of identity, such as misogynoir (hatred directed toward Black women) or other biases that disproportionately lead to violence against Black individuals, such as transphobia (2 in 3 victims of fatal violence against transgender and gender-nonconforming people are Black transgender women).

Even without these more nuanced approaches to the data, it is clear that despite changing economies, political landscapes, and media coverage, Black Americans’ level of risk for hate crimes has prevailed. Black communities only account for 13.6% of the total U.S. population, but each year, about a third of hate crimes specifically target Black Americans. It’s a devastating legacy in the U.S. that’s persisted with little to no federal policy to reverse the course.

You may also like: Notable companies founded by Black entrepreneurs