16 women abolitionists you may not know about

Library of Congress // Getty Images; Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

16 women abolitionists you may not know about

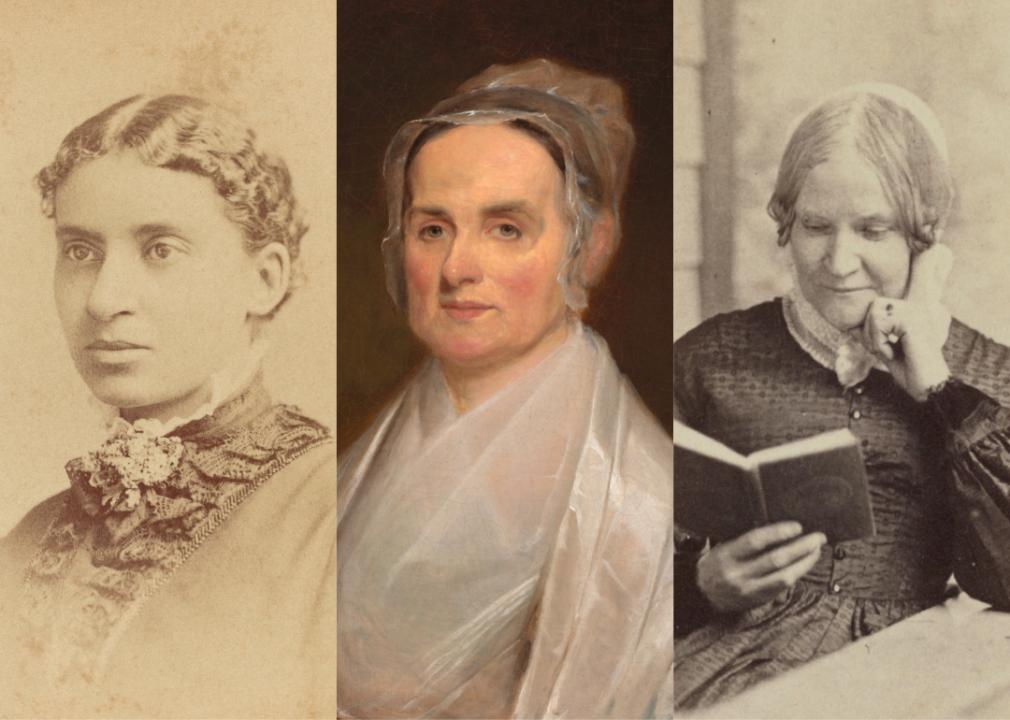

Portraits of Charlotte L. Forten Grimke, Lucretia Mott, and Lydia Maria Child.

It is an egregious fact that forced labor has long been a practice in human history. Evidence of it has been seen in continents and countries since ancient times.

Slavery based on race, however, is a more recently constructed concept that began sometime in the 15th century with the transatlantic slave trade. Backed by European nation-states, it “introduced a system of slavery that was commercialized, racialized, and inherited,” Mary Elliott, curator for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and Jazmine Hughes, writer and editor for The New York Times, wrote for the Times’ 1619 project.

These efforts were deemed abhorrent to some in the British Empire, and sometime in the 18th century, efforts to abolish forced labor and human trafficking began. Those who saw slavery as a shameful practice and sought to upend this system were called abolitionists. These ideas eventually spread to North America as well, where the first stirrings of the abolitionist movement began in states like New York and Massachusetts.

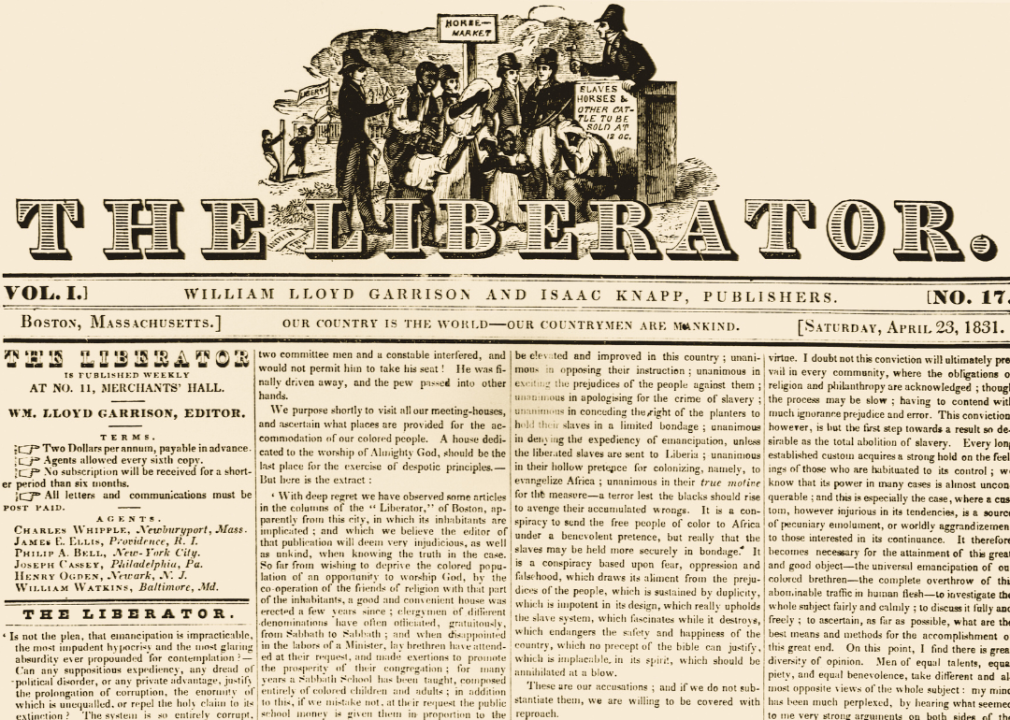

The abolitionist movement began in earnest around the 1820s and by 1833, the American Anti-Slavery Society was formed. While names like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, whose newspaper The Liberator regularly exposed the atrocities of slavery, are names that often come to mind, there were also many women who were instrumental in the fight to end slavery such as Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Sarah Moore Grimké, and Angelina Grimké Weld.

However, the road to freedom was fraught with harsh resistance and opposition—to both the anti-slavery movement itself and the women advocating for it. Many people—even some abolitionists—opposed women’s active involvement in the movement.

Nonetheless, women abolitionists carved their way. They formed their own anti-slavery societies. They organized anti-slavery fairs, signed anti-slavery petitions, and circulated anti-slavery literature. They wrote articles for anti-slavery newspapers, raised funds, and engaged in public speaking against slavery. At a time when women were expected to sit in the background, these heroes shattered those restrictions, bravely and unapologetically standing up for what they believed in.

Along with famous abolitionists, several lesser-known women abolitionists helped in the movement as well, and their impact should not be forgotten. Using multiple sources, such as the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum, the National Women’s History Museum, and the Archives of Women’s Political Communication at Iowa State University, among other sources, Stacker compiled a list of 16 women abolitionists whose names may not be recognized by most.

Keep reading to learn more about how these courageous women activists contributed to the abolition of slavery.

![]()

Library of Congress // Getty Images

Lydia Maria Child

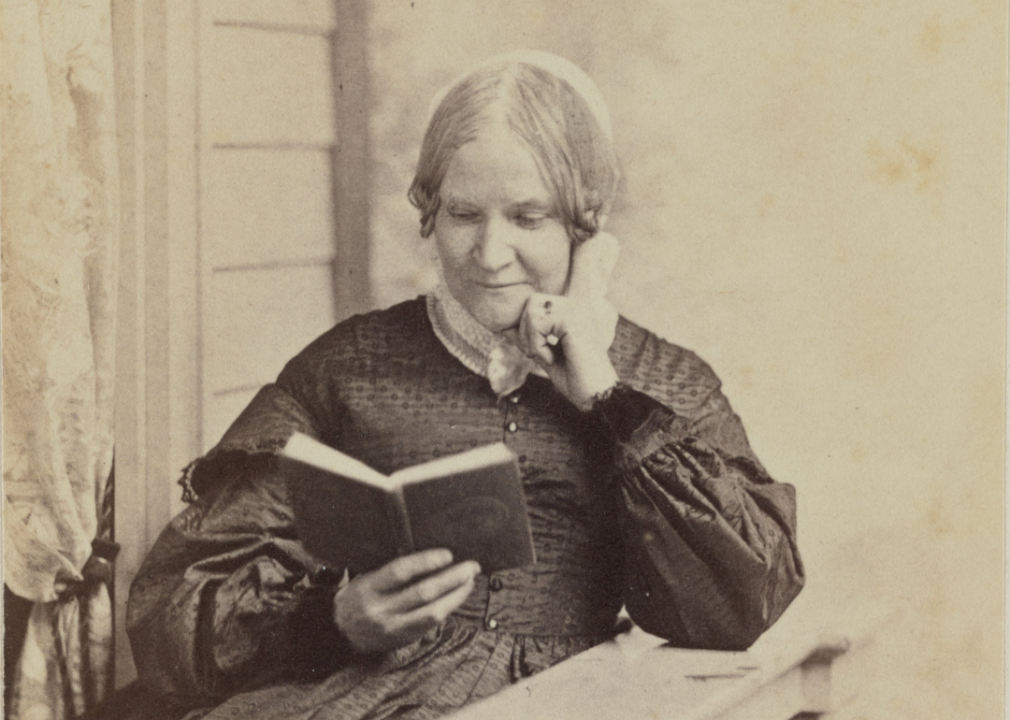

Lydia Maria Child posed reading a book.

One of the 19th century’s most popular writers, Lydia Maria Child paid the price for her convictions. She was the author of a bestselling book on household advice called “The Frugal Housewife” and the founder of America’s first children’s magazine, Juvenile Miscellany.

After meeting William Lloyd Garrison, which spurred her activism, she published her anti-slavery book “An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans” in 1833. The public was so outraged that she lost sales of her books and eventually shut down the magazine.

Despite these hardships, Child continued to advocate for abolition, protesting even through her way of life. In 1838, Child and her husband relocated to a different town to grow sugar beets, an alternative to slave-produced cane sugar, though they left later. The year after, she became part of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s executive committee.

From 1841 to 1843, she edited The National Anti-Slavery Standard newspaper. Even after leaving the Standard, Child continued to write and edit. In 1861, she edited and wrote the introduction for Harriet Jacobs’ book “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” and she published “The Freedmen’s Book” for those emancipated from slavery in 1865.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Lucretia Mott

Portrait of Lucretia Mott by Joseph Kyle.

Lucretia Mott dedicated her life to the twin causes of abolition and women’s rights. A charismatic orator, she often blended these two causes together as a Quaker minister. She also advocated for the boycott of products made through the labor of those who were enslaved.

In 1833, she attended the first meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society and was the only woman to speak. Later, she helped found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial organization run by women.

She was so prominent in the movement that after the dedication of the Pennsylvania Hall, which was built to be used by abolitionists, her home was targeted by a mob carrying torches. Though she waited in her parlor, the mob was eventually diverted by allies.

In 1840, Mott and her husband attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London as delegates, but she was barred from participation because of her sex. Even then, the crowd chanted her name, and she proceeded to give a speech, urging the crowd to purchase goods made without forced labor.

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, Mott’s home became a stop for freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad, and in 1866, she stepped up to become the first president of the American Equal Rights Association. She was also part of the efforts to ensure that Swarthmore College was coeducational. Throughout her life, Mott was dedicated to human liberation in all its forms.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Abby Kelley Foster

Illustration of Abby Kelley Foster from a daguerrotype.

A teacher living in Lynn, Massachusetts, Abby Kelley Foster was influenced by The Liberator and William Lloyd Garrison on the matter of slavery. She used her skills as a lecturer and educator to continually advance the causes of women’s rights and abolition, giving speeches to mixed-gender crowds and even sharing her platform with those formerly enslaved.

Foster joined the town’s Female Anti-Slavery Society, and afterward, was sent by the chapter as a delegate for the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. Foster eventually became the chief fundraiser, general financial agent, and general agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society years later.

Becoming more and more radical as the years progressed, Foster believed in full and legal equality for Black people along with the abolition of slavery. She also encouraged abolitionists to leave churches that did not completely condemn slavery. She left the Quaker church herself in 1841 over a violation of a policy concerning anti-slavery speakers.

Foster married Stephen Symonds Foster and used their property, Liberty Farm, as a stop on the Underground Railroad for freedom seekers. Their home was designated a National Historical Landmark in 1974.

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Engraved portrait of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a household name in her day. One of the first Black women to publish a novel and the first to publish a short story, Harper was also an influential abolitionist who helped found the National Association of Colored Women.

Born a free Black woman, Frances Ellen Watkins worked as a teacher and lived in an Underground Railroad station, where she witnessed firsthand the work of abolition. But it was when Maryland passed a law stating free Black people who entered the state could be sold into slavery that marked the start of her activism.

She gave anti-slavery lectures for several years in the U.S. and Canada, which helped sales of books. Harper diverted a large share of those proceeds from book sales to benefit the Underground Railroad.

In 1866, Harper delivered a memorable speech at the National Women’s Rights Convention, calling for participants to include Black women in the suffrage movement. Apart from helping found the organization, she would serve as vice president of the National Association of Colored Women in 1897.

Throughout her life, Harper continued to publish books that exposed the racism of 19th-century society and showed the struggles of Black people in the United States. In one moving poem, “Bury Me in a Free Land,” she writes, “I ask no monument, proud and high, / To arrest the gaze of the passersby; / All that my yearning spirit craves, / Is bury me not in a land of slaves.”

Fotosearch // Getty Images

Laura Smith Haviland

Portrait of Laura Smith Haviland holding slave irons.

Laura Smith Haviland’s life does not lack in high-stakes milestones. She helped form the first anti-slavery society in Michigan, established one of the first Underground Railroad stations in Michigan, and co-founded the nondiscriminatory Raisin Institute with her husband.

Born in Ontario, Canada, Haviland devoted herself more fully to anti-slavery work after several of her family members died from an epidemic in 1845. Haviland made many trips through Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana enacting elaborate plans to help fugitives escape slavery by making the journey to Canada. Haviland found such great success that Southern owners of enslaved people set a $3,000 reward for Haviland’s capture.

During the Civil War, Haviland helped with relief efforts, and afterward, she continued assisting formerly enslaved people by working with the Freedman’s Relief Association and the American Missionary Association. She also founded an orphanage for Black children. Haviland meticulously wrote down her many experiences in a religious autobiography, “A Woman’s Life Work: Labors and Experiences of Laura S. Haviland.”

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Myrtilla Miner

Students at their desks in a classroom.

Myrtilla Miner first witnessed the horrific reality of slavery while teaching at Newton Female Institute in Mississippi and requested to teach African American girls but was denied. Because of her beliefs, she was forced to leave the state.

She moved to Friendship, New York, where she developed a project that would help uplift Black communities by training African American girls to be teachers—an effort Frederick Douglass considered to be ambitious and dangerous.

Despite this, in 1851, Miner opened a school in Washington D.C. teaching six students, and after three moves, found a permanent location named the Normal School for Colored Girls. The school faced harassment and enraged mobs who tried to burn it down. The mayor publicly condemned Miner’s school in the newspaper, but she persevered and eventually found allies like Johns Hopkins and Henry Ward Beecher, who would serve on the school board.

Though the school had to close in 1860, it opened again as the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth in 1865 and was subsequently assimilated into other institutions that would later form the University of the District of Columbia.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Harriet Forten Purvis

Enslaved people arriving in Philadelphia along the banks of the Schuylkill River from William Still’s history Underground Railroad.

One of the famed “Forten Sisters,” Harriet Forten Purvis was the daughter of influential abolitionists Charlotte Vandine Forten and James Forten. Of biracial background, Purvis worked alongside her mother and three sisters to help found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. Purvis was a co-chair for their anti-slavery fairs, and she also attended the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838 and 1839.

Purvis participated in the society’s sewing committee, which opened a sewing school in a poverty-stricken region. She also helped launch a boycott of slave labor products, such as vegetables, fruit, and cotton.

She married Robert Purvis, who also came from a prominent abolitionist family, in 1832. Purvis and her husband’s Byberry, Pennsylvania, home became a major station on the Underground Railroad for freedom seekers.

During the Civil War, Purvis protested the segregated trolley laws in Philadelphia by sitting in the section reserved for whites. Long before Rosa Parks, Purvis would help overturn inequality in trolleys in the 1860s along with Octavius Catto. Throughout her life, Purvis continued to work on civil rights and segregation issues.

Graphic House/Archive Photos // Getty Images

Elizabeth Gloucester

The girls’ playground of an orphanage for Black children in Manhattan.

Upon her death, Elizabeth Gloucester was thought to be the richest Black woman in the country. Gloucester ran multiple businesses, including an upscale boarding house, and her fortune was worth about $300,000 (or about $7 million today). But it was what she chose to do with this wealth that is as remarkable.

Born free, Elizabeth Parkhill eventually married James Gloucester, who later founded Siloam Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn. The couple’s church supported the cause by donations and support for anti-slavery causes. The church also assured safe passage for runaways and gave a platform to noted figures such as Frederick Douglass and John Brown, a militant abolitionist. Gloucester also raised funds for the Colored Orphan Asylum, which aimed its services toward Black children who were excluded from the efforts of other orphanages at the time.

Canva

Harriet Jacobs

An open journal with handwriting.

Born into slavery in North Carolina, Harriet Jacobs is best remembered for her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” which details the abuses she faced in the household of Dr. James Norcom.

Edited by fellow abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, the book was unheard of at the time. It brought to light the difficult circumstances of a woman who was enslaved, fighting unceasing sexual advances. It also framed the woman as an intelligent hero.

After running away from Norcom, Jacobs lived in a 9-by-7-foot crawlspace for seven years to be close to her children, which she had with a white lawyer. A fugitive and enslaved person, she was constantly on the run, and she eventually moved north to Rochester, New York, and worked with abolitionists. It was Amy Post who urged her to write her autobiography, which has now been translated into multiple languages, including Spanish, French, and Japanese.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Sarah Parker Remond

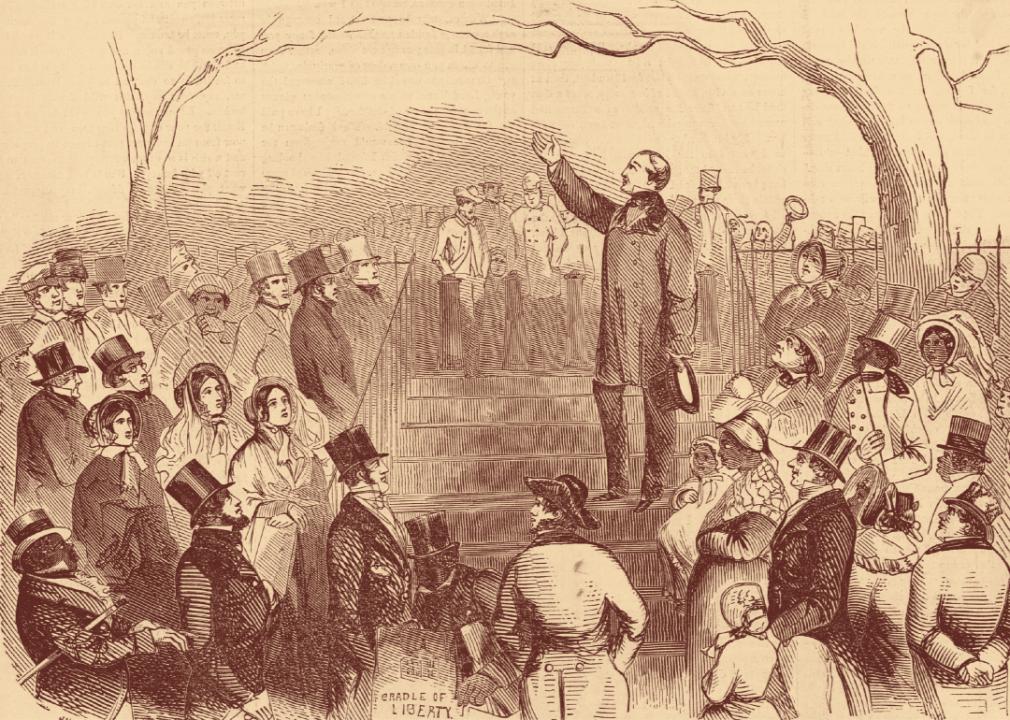

Wendell Phillips delivers anti-slavery speech to a crowd gathered on the common in Boston.

Sarah Parker Remond was transatlantic abolitionist. Born free in Salem, Massachusetts, Remond was part of a family of successful businesspeople. She began to lecture in opposition to slavery at 16.

In 1853, Remond refused to sit in segregated seats at a theater and was shoved down a flight of stairs and forced to leave, but she sued the theater and won, and the theater was ordered to integrate seating.

From 1856 to 1858, Remond gave anti-slavery lectures in the United States for the American Anti-Slavery Society, and later, she gave anti-slavery speeches in Scotland, England, and Ireland.

She was the first woman to speak against slavery in public in the United Kingdom. During the Civil War, Remond advocated for people in Britain to support the Union, and afterward, she gave lectures to raise funds for those emancipated from slavery. She returned to the United States briefly, joining the American Equal Rights Association, but moved to Italy where she married and practiced medicine for more than 20 years.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Maria Stewart

The front page of the April 23, 1831 issue of ‘The Liberator’.

Maria Stewart was one of the first American women of any race to speak in public. Born free, Stewart also published “Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality” in 1831, and in doing so, became the first Black woman to write and publish a political manifesto. Her manifesto inspired four abolitionist lectures in Boston from 1831 to 1833.

Stewart’s speeches used biblical language and even advocated the use of force, if necessary. She encouraged Black audiences to pursue education and fight for political rights. “Sue for your rights and privileges,” Stewart wrote.

In 1834, she moved to New York where she joined a Black and female literary society and also taught. She moved to Baltimore and later relocated to Washington D.C., where she became a nurse at the Freedmen’s Hospital, now known as Howard University Hospital.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Charlotte Forten Grimké

Studio portrait of Charlotte L. Forten Grimke.

Born free in Philadelphia to a prominent family of abolitionists, Charlotte Forten moved to Salem, Massachusetts, where her interest in abolition was kindled. In Salem, Grimké attended anti-slavery lectures, wrote poems opposing slavery, and joined the Female Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1862, Forten went to St. Helena Island, South Carolina, to teach formerly enslaved people who were left behind by plantation owners fleeing the Union forces. This was called a “rehearsal for Reconstruction.”

Forten kept detailed journals when she taught in South Carolina. Her writings were then published in Atlantic Monthly as a two-part essay entitled “Life on the Sea Islands” in 1864. That same year, she married Francis James Grimké, who was the nephew of Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld. Later, in 1896, she helped found the National Association of Colored Women, working to advance civil rights throughout her life.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

Reproduction of ‘The Underground Railroad’ painting by Charles T. Webber.

When Frederick Douglass’ North Star newspaper asked readers what could be done to improve Black lives, Mary Ann Shadd Cary wrote, “We should do more and talk less.”

Shadd Cary was born free and lived in an abolitionist home that frequently saw enslaved people who were on the run. After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which compelled Americans to help capture those who ran from enslavement, Shadd Cary and some of her family moved to Canada.

In Canada, Shadd Cary published writing that advocated for Blacks to immigrate there, and she also founded the anti-slavery paper The Provincial Freeman, which made her the first Black woman newspaper editor in North America.

When the Civil War began, Shadd Cary came back to the United States to help recruit Black soldiers for the Union Army. She also moved to Washington and founded a school for the children of the formerly enslaved after the war. Later in life, Shadd Cary earned a law degree, becoming one of the first black women lawyers in the U.S.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Prudence Crandall

Engraving of Prudence Crandall.

Prudence Crandall bravely kept to her beliefs and fought against systems of racial discrimination by opening one of the first schools for African American women in Connecticut in 1833.

In 1831, Crandall opened a girls’ academy that soon became one of the best in the state. The next year, Crandall admitted a controversial student: a young black woman named Sarah Harris. Harris’ admission was met with intense hostility and opposition from the townspeople, but Crandall stayed firm in her decision.

She continued to attract African American students aided by support from Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator. In response, the town continued its vehement opposition, taunting African American students with stones, eggs, or manure. When 1833’s Black Law made it illegal to teach African American students from states other than Connecticut, Crandall was arrested. Though her arrest was overturned in higher courts, Crandall finally closed the school to protect her students’ safety.

She would eventually leave Connecticut and move to Illinois where she would continue in education. Crandall is now named Connectictut’s state heroine.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Lilly Ann Granderson

Young girl reading at desk.

Education is truly a prize, especially for those who were enslaved. In the South, anti-literacy laws kept much of the enslaved population from working to better their lives. Through her midnight efforts, Lilly Ann Granderson helped uplift her community.

Born into slavery in Virginia, Lilly Ann Granderson was later sent to Kentucky, where the children of her enslaver taught her to read and write. Granderson was eager to learn and to share her newfound knowledge. She would teach others on Sundays, hiding in the woods and drawing letters on the ground.

After the death of that first enslaver, she was sent to Mississippi where she initially worked in the cotton fields, but was transferred to Natchez after suffering from the heat and labor. In the Natchez house, Granderson managed a clandestine school that ran from 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. each day, teaching 12 students at a time. In a time span of seven years, hundreds of enslaved people attended Granderson’s school and learned to read and write.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Sarah Mapps Douglass

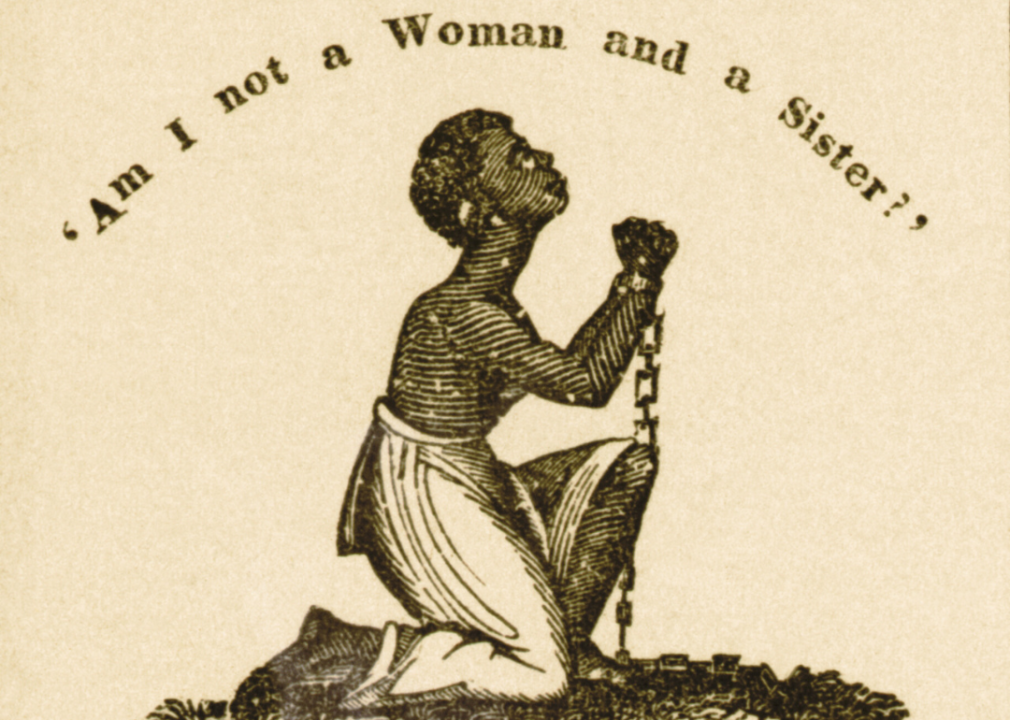

“Am I not a woman and a sister” illustration – a symbol of the women’s abolitionist movement.

Granddaughter to Cyrus Bustill, a founder of the Free African Society, Douglass was an educator, artist, and abolitionist. Her works are one of the earliest examples of art signed by an African American woman.

In 1831, Sarah Mapps helped found the Female Literary Association for Black women, which encouraged self-improvement. Societies like these often catalyzed activism in their members.

In 1833, she helped found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society led by Lucretia Mott. She would be involved in work for this organization for most of her life, organizing programs that would encourage an end to slavery, including procuring signatures for petitions and boycotts.

Though she originally thought of becoming a doctor, she eventually chose to become a teacher and worked at the Institute for Colored Youth, where she worked for the cause of the formerly enslaved.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.