With Texas' paper-based voter registration system, applications get lost in the shuffle

Gabriel Cárdenas for Votebeat

With Texas’ paper-based voter registration system, applications get lost in the shuffle

Hannah Murry poses for a photo at Texas A&M University.

Last year, Hannah Murry remembers, she filled out every line of her paper voter registration.

She then gave it to a volunteer deputy registrar at a registration drive at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, where she’s a student.

“I thought that was handled, so I just went on with my life,” said Murry.

It wasn’t handled.

Murry, 21, pictured above, found that out when she went to an early voting location in Nueces County last fall to cast her first ballot, in the constitutional amendment election.

She handed her ID to an election worker—who told her she wasn’t on the rolls.

At that point, it was too late to fix it. Poll workers let her update her registration on site for the next election, which she did. She left confused and frustrated.

“I went there ready to vote, ready to be engaged, and then I was not able to,” she said.

The same thing happens to people all over Texas, a Votebeat investigation found: Eligible voters who believe they have done everything necessary to cast a ballot don’t get the chance because their registrations didn’t make it into the system.

There is no simple way to know how many people are disenfranchised because of this, but more than a dozen local election officials and volunteer deputy registrars shared examples, and multiple people told similar stories: They filled out the paper application form, mailed it, gave it to a volunteer deputy registrar, or even went to their county office to drop it off—and still weren’t successfully registered.

Votebeat’s investigation found the problems apparently share a root cause: a registration system that relies on paper forms. Texas is one of only eight states without universally available online voter registration. Most people in the state have to fill out a paper form, whether they are registering through an election office or while getting a new driver’s license or state ID at the Texas Department of Public Safety. Only people who already have a Texas driver’s license and are engaging in an online transaction with DPS, such as renewing their license or updating their address, can use a DPS online portal to register.

The Texas Secretary of State’s office told Votebeat that offering online registration to all voters would require legislative action. State lawmakers have for years resisted efforts to do so.

That means information from hundreds of thousands of applications processed each year has to be entered into county election systems by hand—creating plenty of opportunities for things to go wrong.

Attempts to register via DPS, which handles roughly 2 million voter registrations a year, also didn’t always work. Public records obtained by Votebeat via a records request show election officials from at least 41 different counties contacted the agency during either the November 2022 general election or this year’s primary about more than 100 people who said they registered at DPS, but didn’t make it onto the rolls. Dozens of other inquiries to the agency sought information about voters whose DPS applications were incomplete, records show.

Election officials say the volume increases during presidential election years, making it more likely that some registrations could slip through the cracks.

“You want to be able to tell people, ‘You can do this, you can fill this out, check this box and you’ll be fine’ and that ‘Yes, you can trust in this system,'” said Valerie DeBill, vice president of voter services at the League of Women Voters in Austin, and a volunteer deputy registrar. “And it just doesn’t seem to really work the way that it’s supposed to.”

Volunteer deputy registrars, like the one who collected Murry’s application on campus, are legally required to bring all completed applications to county election officials. But that doesn’t ensure that they get properly recorded.

In Murry’s case, Nueces County received the form, according to Brenda Nuñez, the county’s voter registration supervisor, but it didn’t update her record to replace an earlier registration in Jefferson County.

Murry said she didn’t receive anything in the mail after updating her information at the polls, but ultimately registered successfully through another volunteer deputy registrar she knew personally. She voted in the primary earlier this year in Nueces County.

“We research. We do the best we can to read voters’ handwriting, and to try to reach them to correct an issue [with the application] so they don’t get rejected, but it doesn’t always work,” said Nuñez, adding that voters also make errors. “They can transpose a number or forget to check a box. But we can make errors, too. We try to do our best, but it can happen.”

![]()

Gabriel Cárdenas for Votebeat

Errors and hurdles can slow registration

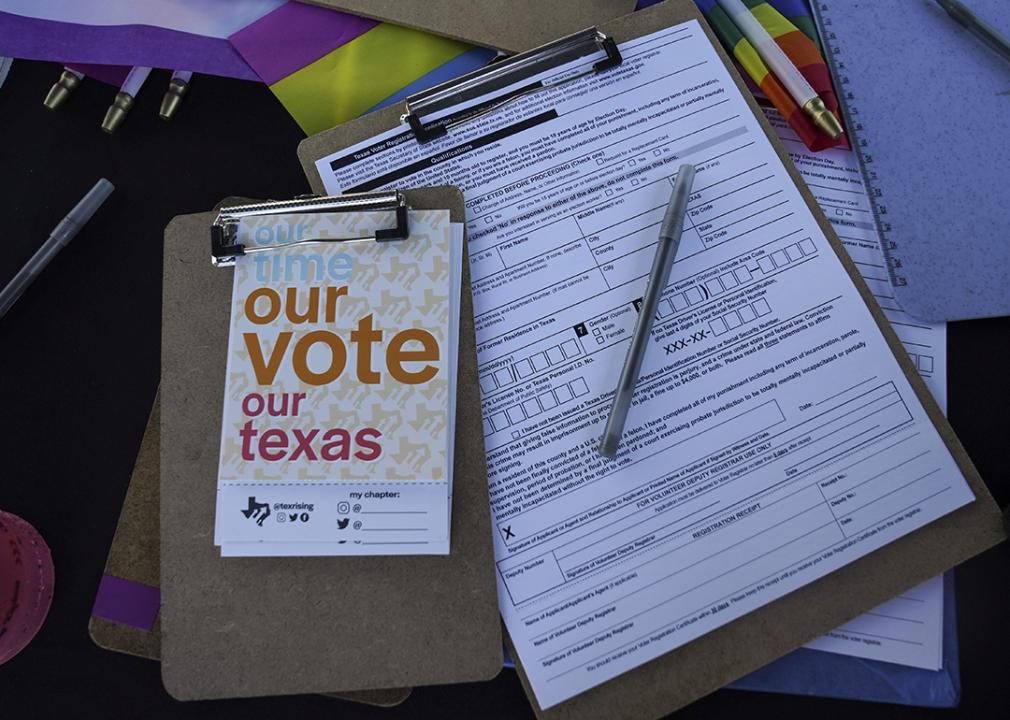

Applications to register to vote are seen at the Texas Rising tent during a Pride celebration in Corpus Christi, Texas on Oct. 5, 2024.

Texans must be registered to vote at least 30 days before the date of an election. Blank applications that voters can print out and complete are available online, as well as in any U.S. post office, at offices of the Health and Human Services Commission, the Texas Workforce Commission, and DPS, and at public libraries. Or voters can get them at registration drives at community events or college campuses.

County officials in charge of voter registration have workers assigned to process the forms as they come in. That includes manually entering the information on them into the county’s database. The applications are then scanned as images, and the physical forms are shredded once the registration is approved and the voter registration certificate is mailed. Large counties such as Travis and Collin hire several temporary workers to help staffers process registrations.

In Nueces County, which has more than 200,000 registered voters, Nuñez has two other full-time staff members and brings in four temporary workers to help them process the hundreds of forms that arrive daily during an election season. Retired city employees alphabetize the applications, check them line by line, and enter the information into the system.

As early voting for the November election got underway, Nuñez and her staff were flooded with phone calls from voters. Some said they tried to vote and couldn’t because they weren’t on the rolls. Others called because they were registered in another county and didn’t update their information on time.

Errors on applications slow things down, and workers can’t always reach the applicant to fix them in time for the next election.

At a September voter registration drive in Corpus Christi, a voter filled out his application and left. While reviewing it, volunteer deputy registrar Alex Flucke realized the voter had made a mistake on the street address. But the voter did not leave a phone number. In a case like this, election workers may try to look up the correct address, using maps and other resources. They’ll also likely mail the prospective voter a notice—though the inaccurate address could keep it from being delivered.

Flucke, 29, who is the vice president of voter services with the League of Women Voters in Corpus Christi, said applicants make errors all the time. “People don’t put their address, people don’t know their address, people don’t have their driver’s license, especially at high schools, and a lot of times they don’t know the last four [digits] of their Social Security number,” Flucke said.

She’s seen voters who forget to check the boxes at the top of the application asking whether they are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen.

“Every issue that you can experience with people filling out those forms, I’ve seen,” Flucke said.

Volunteer deputy registrars play an important role in the process, especially in larger counties, where they help generate a large volume of registrations through community outreach. But there are many steps they must follow. Texas has strict laws requiring anyone registering voters for a county to be certified as a volunteer deputy registrar in that county. Some counties offer online training, while other counties’ require training in person.

There’s no way to become certified statewide, which means volunteer deputy registrars often can’t accept applications from people who live in neighboring counties. They can offer a form from the Secretary of State’s office, but the voter must mail it back to that office, which forwards it to the voter’s county. Two weeks after the voter registration deadline, some counties were still receiving applications in the mail from the Secretary of State’s office.

Volunteer deputy registrars turn in all the forms they collect to county election officials, like Shannon Lackey, the elections administrator in Randall County.

“So many times those applications come in to us and they are nearly illegible, and so we are having to guess what their name is,” Lackey said. Often voters don’t realize that they have to put their legal name or exactly as it appears on their Social Security card, state ID or driver’s license, she added.

Voter registration applications go astray

Since 2021, more than 2 million Texans have annually registered to vote through DPS, either through the paper forms or the web portal available to people who renew or update their state IDs or licenses. In just the first eight months of this year, that figure surpassed 3 million people.

But DPS employees can’t directly add someone to the voter rolls. The information they collect has to be conveyed first to local election officials through the state’s voter registration system, TEAM.

Sometimes, the information goes astray. In other cases, election officials told Votebeat, those applications are transmitted without the voter’s address, or with incorrect street names—information that election officials must have to assign voters to the correct precinct.

Enough registrations go astray that TEAM has a designated portal for election officials to submit inquiries to DPS about missing registrations. It’s also used to double-check a voter’s address or driver’s license number when that information is missing or unclear. There’s also a designated email address for such requests. Records obtained by Votebeat show a steady stream of inquiries.

“The following voters stated that they registered through DPS in order to change their address prior to Oct. 11, 2022,” Cynthia Lum, the election official from Houston County (population around 22,000), wrote in an email, listing 11 voters and asking the agency to check its records.

In an interview, Lum said that 2022 was the first time the county had such a high number of missing applications tied to DPS, and that the agency has improved.

As for the 11 voters she asked about in 2022, she could not say what the response was from DPS in each case. But she said such voters can cast a provisional ballot that gets counted once DPS is able to find and forward their completed registrations. Those who didn’t check “yes” on the small box asking if they wanted to update their voter registration remain ineligible, and their provisional ballots aren’t counted.

In November 2022, election officials in East Texas’ Nacogdoches County asked DPS about more than a dozen voters’ applications. Anderson County officials sought applications for 21 voters who said they’d registered at DPS but were not on the rolls and had to cast provisional ballots.

In North Texas, Kaufman County election officials sent DPS a list of 59 voters, records show, and an email from Tandi Smith, the Kaufman County elections administrator, said all “have sworn provisional affidavits attesting that they registered with DPS since moving to Kaufman County.”

Smith then underlined and bolded one sentence: “Your response is critical in determining if their ballot is counted.”

In an email, Smith said she didn’t have time to respond to specific questions from Votebeat about her inquiry.

Doreen Geiger of Tarrant County, who has been a volunteer deputy registrar for two decades, told Votebeat she often advises new voters against registering to vote through DPS. “It’s just not very reliable,” Geiger said. “Give it directly to the elections office.”

Some voters who registered at DPS said they got to vote only because they stayed vigilant.

Sophie Sutherland, an Austin resident and native of England, obtained her American citizenship last year after living in the U.S. since 2005. But shortly before her naturalization ceremony, her purse was stolen. She decided to wait until after the ceremony to replace her license, so she could register to vote at the same time.

At DPS, she filled everything out and asked the clerk if she needed to do anything else. “No, that’s it. We’ve got it from here,” Sutherland recalls the clerk telling her.

But when she went to check on her registration online on Feb. 5, the deadline to register for the March primary, it wasn’t there. She quickly called a friend who’d been a volunteer deputy registrar who told her to immediately mail a new application and ensure it was postmarked that day.

That worked. But “most people are not going to be able to find the time or go to the bother,” she said. “Some people simply can’t.”

DPS officials didn’t respond to specific questions about why some applications fail to make it to county election officials. But in an email, the agency said the remedy is for election officials to contact DPS so the agency can check whether the person indeed selected “yes” on the voter registration application question.

To help prevent errors, DPS customers are asked to verify their selections before transactions are finalized, said Sheridan Nolen, the DPS press secretary. That happens via a printout in person and through a confirmation page online, Nolen said.

A voter whose registration doesn’t come up on the voter rolls at the polls can cast a provisional ballot. More than half the nearly 39,000 provisional ballots cast in the state in the 2022 general election were due to the voter not being on an eligible voter list, according to data tracked by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, though it’s unclear how many of those voters said they had tried unsuccessfully to register.

If the voter tells election officials that they registered at DPS, election officials are legally required to investigate. Sometimes, voters are wrong—they think they registered when they actually didn’t. But if election officials are able to find the completed application, the voter’s provisional ballot can then be counted. Days after Election Day, voters are notified by mail whether or not their provisional ballot was counted.

The push for online registration stalls

Voters and some election officials say there ought to be a better way to make sure registrations stick.

Charles Williams, 69, a retired railroad conductor, mailed his voter registration application in June to the Travis County voter registration office. Two months later, Williams hadn’t received a confirmation.

His wife, who has been an election worker in Travis County, encouraged him to check on it, and after he did, it took Williams months of waiting, multiple calls, and repeat applications before he was able to confirm that he was registered. “I want to make sure I am able to vote in November,” he said.

His wife, Carla Jackson-Williams was outraged by the obstacles.

“I think they should allow you to go ahead and submit that application online, and then follow up with a written one,” she said. “At least then there is a record of someone who has applied, right? There’s a record and they can’t say it disappeared or that they don’t have it,” she said.

Bruce Elfant, the Travis County tax assessor-collector and voter registrar, said Williams’ experience is why he has, for years, advocated for online voter registration.

“I don’t know why the state is not willing to bring voter registration into the 21st century,” said Elfant, whose term ends in December. “I don’t know what business would operate like this, but we’re operating this aspect of the state government like this, and it’s shameful.”

The only form of online voter registration in Texas is through DPS, and the only people who can access it are those who already have a state ID or driver’s license and are updating their information through the agency’s online portal.

That option became available only three years ago, after voting rights advocates sued the secretary of state and DPS, alleging they were violating federal law by not providing Texans the option to register to vote online while updating and renewing their identification. To settle the case, the state agreed to allow those voters to use the online portal in those circumstances.

But Beth Stevens, a voting rights lawyer who represented the plaintiffs, said she knows it doesn’t always work.

Last year, State Rep. John Bucy of Austin, a Democrat, proposed bills that would direct the Texas Secretary of State’s office to create an online voter registration system.

The bills never got a hearing. He told Votebeat he hasn’t gotten a clear answer as to why. He plans to propose it again next year.

“This should have happened a long time ago,” Bucy said. “The problem is, we’ve got political leaders that care about their power over voter access, and so they’ve stopped it. But we know this works.”

Texas Governor Greg Abbott has yet to publicly take a stance on online voter registration. His office did not respond to requests for comment.

The last time lawmakers held a hearing on the issue was in 2015. At the time, Republicans raised concerns about whether it would enable voter fraud and identity theft. Supporters argued that the same risk existed with the paper forms, which ask voters for sensitive identifying information. Those forms are then handled by multiple people.

The lack of a voter’s signature on an electronic form was another concern. Supporters told legislators at the time that other states have addressed that by requiring voters to have a state ID or driver’s license in order to register electronically.

That’s now the case in Alabama, which implemented online voter registration in 2016. Residents there can register online, once they have a state ID or driver’s license on file, said former Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill, a Republican.

“We’ve never had a breach where any of our data had been corrupted, no improprieties, no concerns, no vulnerabilities have ever been exposed,” Merrill said. “You have to remember all of that has to be added to the voter roll by the local registrar, who still has to verify identity and verify the voter is qualified. No one is automatically added to the rolls. There’s still a process that has to be followed.”

Before Kentucky implemented online voter registration in 2016, the state relied on volunteers to return forms to the county, as Texas does. Sometimes those forms would not get turned in, said former Kentucky Secretary of State Trey Grayson, a Republican. Election workers dealt with backlogs of applications, errors in the forms, and typos.

But now, once a Kentucky voter fills out the form electronically, they receive an email confirmation, Grayson said.

“The confirmation is essentially like your receipt. It shows that a transaction happened, and that’s comforting for the voter,” he said. “It’s also a positive to the election administrator, because the worst thing that happens is when that voter comes out on election day and they’re not on the list.”

Online voter registration saved the state millions of dollars, led to more accurate voter rolls, and reduced backlogs and long lines during elections, Grayson said.

“There’s 43 states that have it,” Grayson said. “Nobody’s repealed it. It’s not controversial in these states. It’s just the way it’s done.”

This story was produced by Votebeat and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.