80% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable—here's a closer look at maternal mortality in the US

wutzkohphoto // Shutterstock

80% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable—here’s a closer look at maternal mortality in the US

Woman lying in hospital bed.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, around 700 women die from pregnancy-related complications each year in the U.S.—this number only continues to rise.

“Pregnancy-related death” encompasses a broad scope compared to “maternal mortality,” which is more narrowly defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days from the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.”

Pregnancy-related deaths include those occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, and up to a full year postpartum. This category also encompasses the causes of maternal mortality, such as hypertension, preeclampsia, and hemorrhage, as well as suicide, homicide, drug overdose, and car accidents occurring within one year of delivery.

Clarifying this distinction is crucial to understanding the disproportionate risk associated with each. While the U.S. has a higher maternal mortality rate than some developed nations, it’s perhaps even more shocking that 4 in 5 pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

To raise awareness about this national crisis, Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to review data from the CDC to explore why there is prevalence of preventable pregnancy-related deaths. The research shows that the most common cause of pregnancy-related death varies depending on when the health problems occur. While heart disease and stroke are the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths overall, severe bleeding or amniotic fluid embolism cause the most deaths during childbirth; high blood pressure, infection, and heavy bleeding cause the most during the week immediately following delivery; and weakened heart muscles cause the most deaths from one week to a full year after delivery.

Read on to find out how the U.S. compares to other developed nations in addressing this care gap in preganancy-related deaths, which demographics are most affected, and what is being done to improve health outcomes.

![]()

Northwell Health

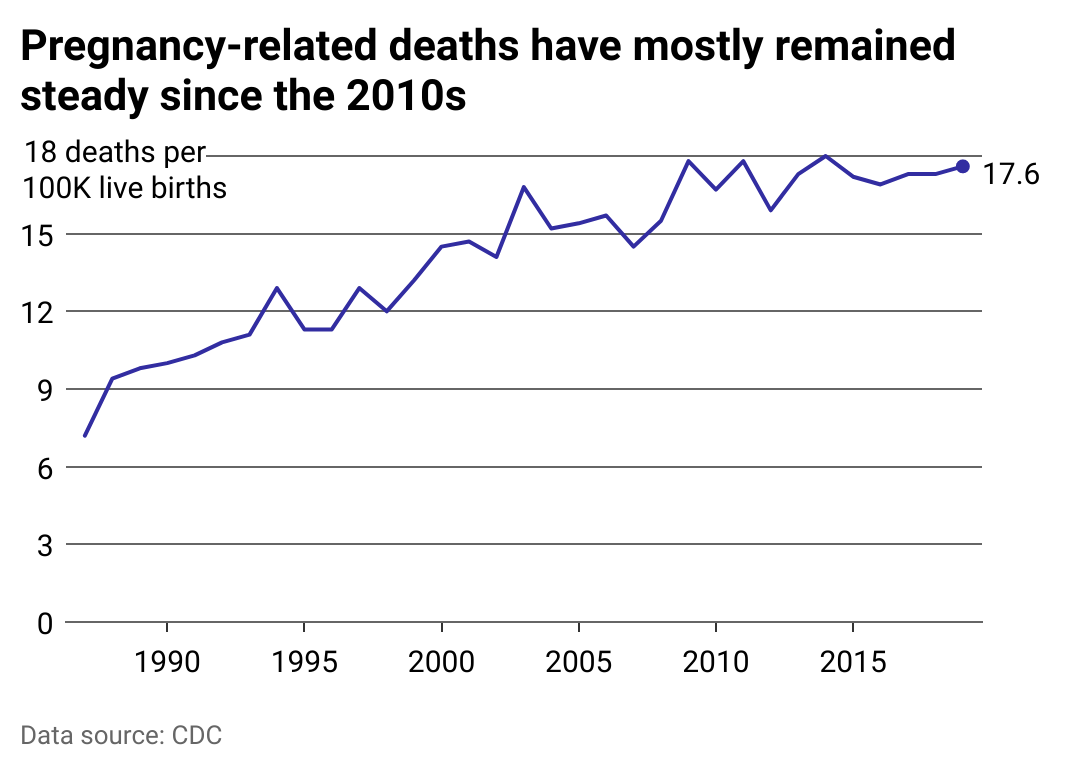

Before the pandemic, the rate of pregnancy-related deaths approached 18 per 100,000 live births

Line chart showing the rate of pregnancy-related deaths over the past 30 years. Since the 2010s, pregnancy-related deaths have mostly remained steady since.

The CDC implemented its Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System in 1987. Since that time, pregnancy-related mortality has trended steadily upward.

While the CDC cannot fully pinpoint why this is the case, it surmises that it could be partly due to the commensurate improvement of data systems, such as the PMSS, in documenting these deaths, leading to an increase in reported deaths overall. Moreover, the nationwide adoption of pregnancy checkboxes on death certificates in 2018 undoubtedly helped identify overlooked deaths, despite their relative ineffectiveness as qualifying pregnancy-related deaths from causes such as accidents or substance abuse.

The CDC reports that the underlying causes of pregnancy-related death from 2011 to 2015, were split nearly evenly among deaths during pregnancy; during delivery or the following week; or within one year of delivery—roughly one-third of all deaths equally. Within those time frames, heart disease and stroke were the leading causes of death, accounting for 34% of fatalities, while infections and severe bleeding were also influential causes.

Later data covering 2017 to 2019 showed that heart-related issues, along with infection and hemorrhage, remained the leading cause of death. Unfortunately, this CDC data does not qualify in further detail deaths attributed to “other cardiovascular conditions” and “other noncardiovascular medical conditions,” which leaves a measure of uncertainty regarding minor and potential trends in the cause of death.

Thankfully, many of these all-too-preventable conditions that lead to fatalities are gaining some increased attention. The CDC’s Eliminate Maternal Mortality Program recently granted $2.8 million for nine new Maternal Mortality Review Committees, which review pregnancy-related deaths on a state or local level to establish recommendations for preventing future deaths. MMRCs are currently operating in 39 states and one U.S. territory. Their research is helping to expand insurance coverage and improve long-term post-childbirth care.

Northwell Health

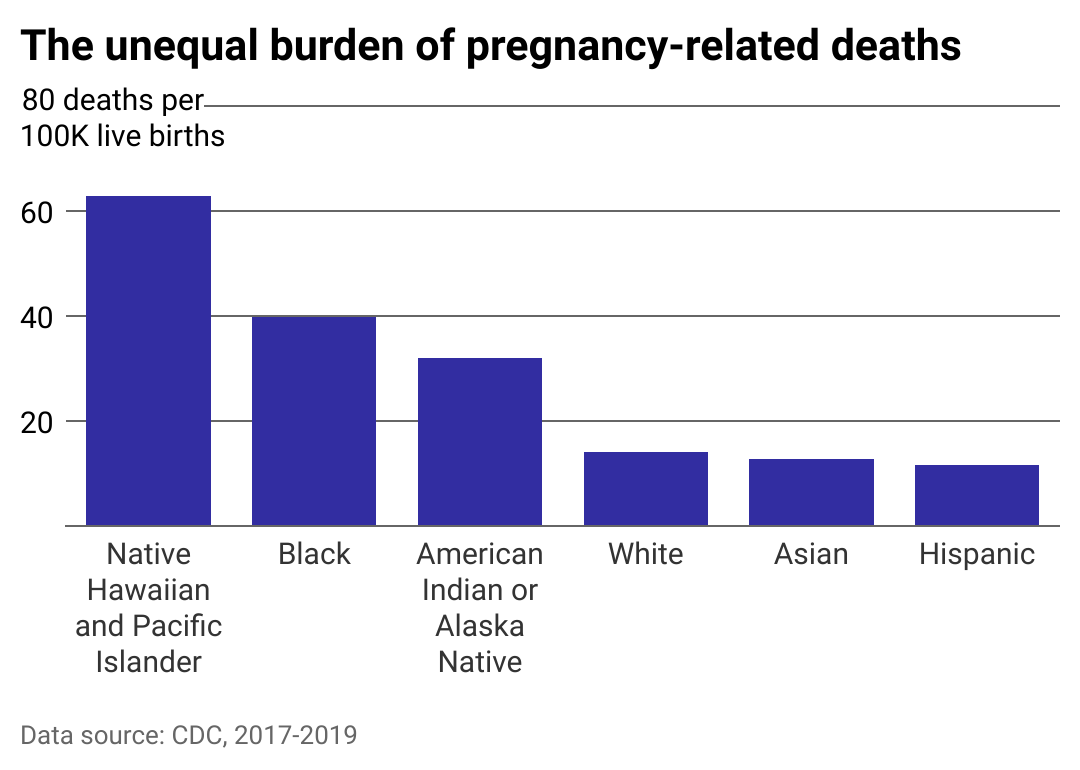

The overall national rate obscures significant racial disparities

Column chart showing that between 2017 and 2019, Native American and Black people face the highest rates of pregnancy-related deaths.

Maeve Wallace, associate director of the Mary Amelia Center for Women’s Health Equity Research at Tulane University, participating in a webinar on pregnancy-related death in the U.S., unequivocally stated that pregnancy-related mortality is a “racialized issue.”

As shown here, the most recent findings by the CDC indicate that Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Black, and Native American/Alaskan women experience death rates at least twice and up to four times higher than white women.

A study from the Kaiser Family Foundation suggests this inequity becomes exacerbated once education level is taken into account. The risk of pregnancy-related death for Black women with a college degree or higher is more than five times that of white women with the same educational level and nearly twice that of white women with less than a high school diploma.

To that end, many medical professionals have called attention to the institutionalized marginalization of specific racial groups in health care. Moreover, one of the primary hurdles to adequate care both during and after childbirth concerns medical insurance. Not only are people of color less likely to be insured, but they are also more likely to face additional hurdles to accessing culturally and linguistically appropriate care—hurdles white people generally do not face.

Such systemic discrimination has been proven to drive unequal access to public health care and result in uneven health outcomes across populations. Within maternal care specifically, the 2019 “Giving Voice to Mothers study” found that women of color are much more likely to experience mistreatment, such as being shouted at, stonewalled, ignored, or otherwise mistreated during childbirth.

Many proposed solutions are taking into account the inequities inherent in pregnancy-related deaths, which disproportionately affect Black, Pacific Islander, and Native American women, by, for example, addressing transportation obstacles to health care deserts in rural areas or supporting community-based doulas who can understand their patient’s background and better advocate for them.

In 2021, the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act was introduced in Congress, which comprises 13 individual bills that would invest in critical areas including more community-based support organizations for Black women, veterans, and incarcerated mothers; better data collection and quality measures to identify and flag poor care in more communities; and improved payment models that incentivize health care providers to offer better quality maternity and postpartum care.

Northwell Health

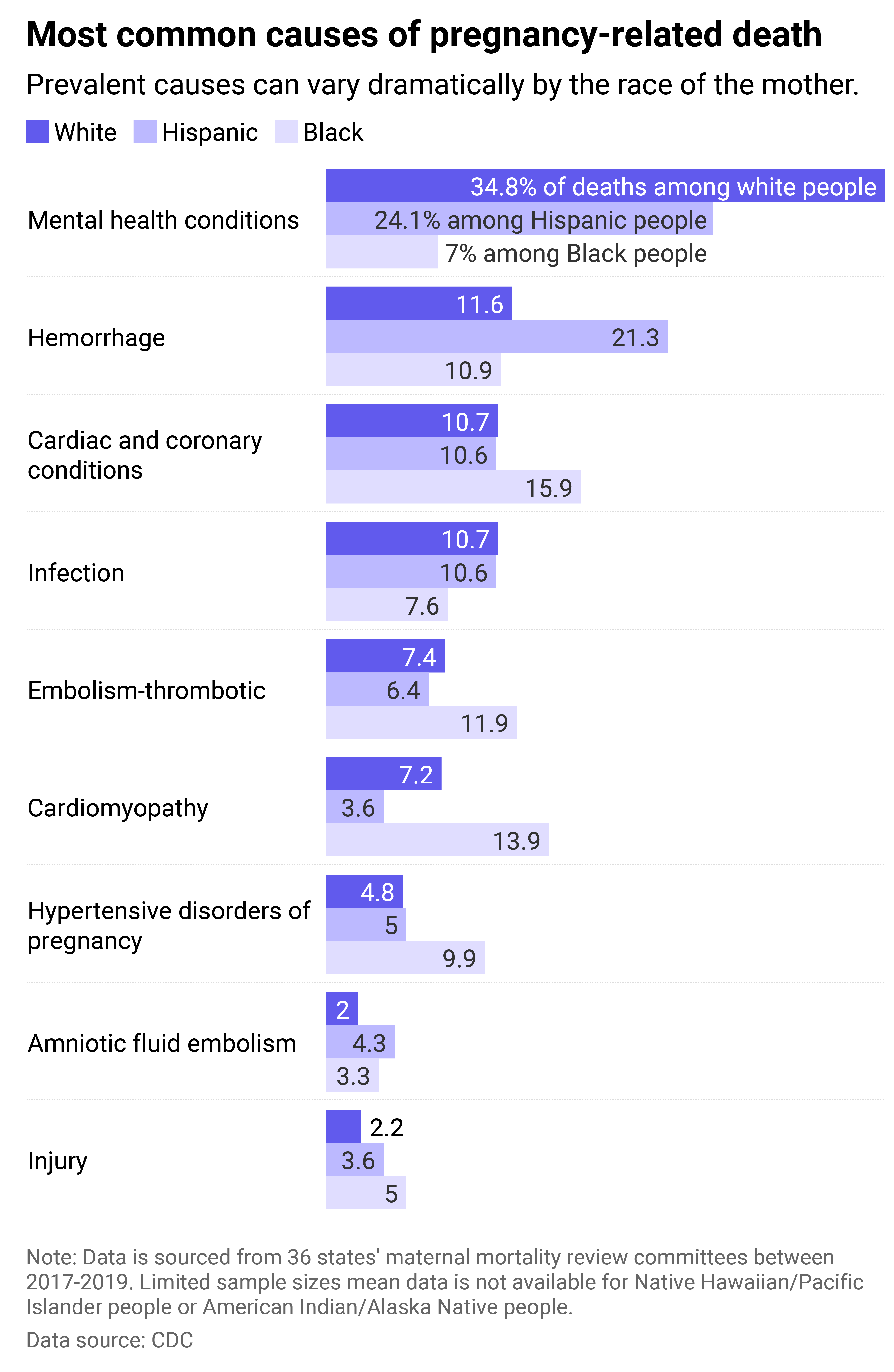

Causes of death demonstrate additional disparities

Column chart showing mental health issues including substance abuse and suicide are the most prominent causes of pregnancy-related deaths, but are less common for Black mothers.

Some conditions increase any woman’s risk of dying during pregnancy or postpartum, regardless of race or income level. More and more pregnant persons across the U.S. are reported as having hypertension, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease, all of which increase their risk of death during pregnancy or the year after. Nonetheless, some conditions disproportionately affect women of color, even without pre-existing conditions.

Mental health issues, including suicide and substance abuse, are now better understood as contributing to deaths during the postpartum period and are more present in certain racial groups than in white women. Compounding this problem is an inequity in screening and diagnosis.

One 2020 study cited in Scientific American found that Black women were 36% less likely to receive postpartum depression screening than white women—and Native American, Native Alaskan, Hawaiian, and multiracial women were 56% less likely.

Additionally, many women of color experience particularly intense social stress, economic pressure, and other vulnerability in the year after giving birth, exacerbating their heightened susceptibility to pregnancy-related mortality during that time.

Fortunately, a growing awareness of the scope of pregnancy-related deaths is shining more light on the importance of the postpartum stage for physical and mental health. There is an increased understanding that a woman’s maternal health journey is only beginning, not ending, once they leave the hospital after giving birth.

Many women find themselves experiencing increased stress and feelings of vulnerability following this time, and often are unaware of maternal health warning signs. Initiatives to better serve women postpartum include the CDC’s Hear Her campaign, which includes multilingual resources detailing symptoms such as dizziness, chronic headaches or swelling, which may seem harmless, but can signal more serious issues in the year post-birth. The program also offers conversation guides for documenting symptoms and talking to health care providers to encourage women to speak up about things that don’t feel right.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.