How the demographics of organ donors differ by state

Canva

How the demographics of organ donors differ by state

A medical technician takes notes in an operating room.

Scientists and physicians have been experimenting with organ transplantation for centuries, with the first successful transplants in the 1950s. But science has come a long way since then.

One of the primary obstacles to a successful organ transplant is ensuring that the recipient’s body doesn’t reject the donor organ. A patient’s immune system may attack a transplanted organ by identifying it a foreign threat, which can lead to damage or destruction of tissue. In the 1970s, a scientist named Jean Borel discovered cyclosporine, a game-changing drug that was later approved for organ transplants to help suppress the recipient’s body’s attack on the donor organ.

Medical science continues to advance, providing new opportunities for organ transplants that save lives. In June 2023, researchers discovered the success rate for heart transplants from donors whose hearts have stopped beating but are not yet brain dead (called circulatory death) is approximately equal to the success rate from donors who have traditionally been allowed to donate: those fully deceased or those who are brain dead. This advancement in heart reanimation could enable more people to donate their organs, potentially saving hundreds of lives.

For people in need of new kidneys, livers, hearts, and more, these technological advances represent not only an improved quality of life, but often a life-saving opportunity. To better understand the advancement of life-sustaining organ transplant surgeries, Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to examine how the demographics of organ donors differ by state using data from the Organ Procurement & Donation Network (OPTN). Read on to discover trends in organ donation and how communities differ across the country.

![]()

Northwell Health

Donor gender

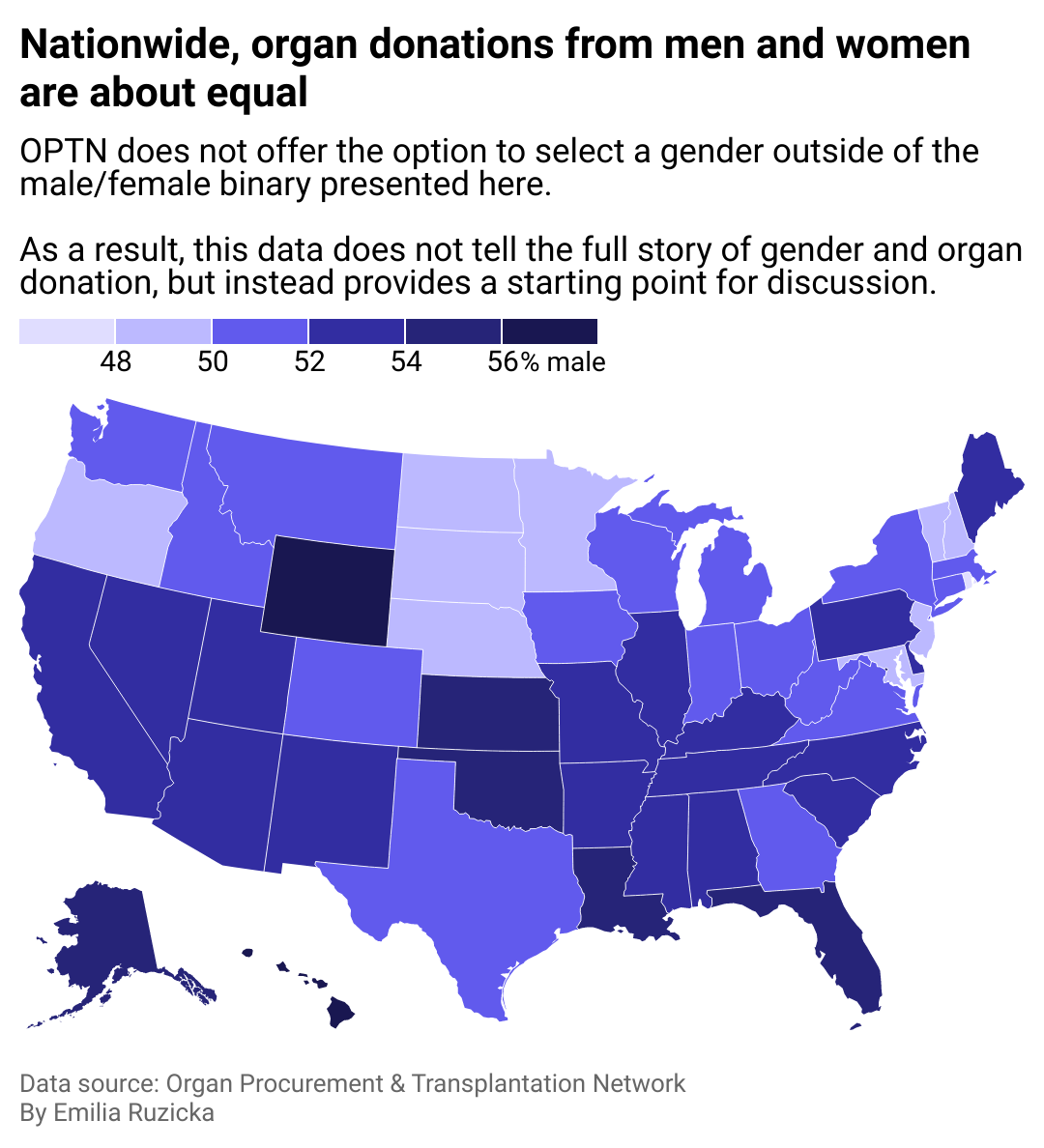

A map of the U.S. showing that nationwide, organ donations are about equal between men and women.

For donors, no restrictions exist based on sex, gender, or sexual orientation. However, one question that physicians and scientists have long studied is whether the sex of the donor and recipient need to match to improve successful outcomes. A 2016 study of organ donation in Italy could not conclusively answer this question.

Another study by Brigham and Women’s Hospital noted that donor sex should not be a concern for recipients undergoing a transplant, but did find that kidney and cardiac transplants were associated with a slightly increased rate of rejection from female donors in male recipients. Among patients aged 45 and older, a female donating to a female patient had a positive effect on acceptance rate. The study also noted that further study is required to understand to what extent transplant outcomes are influenced by molecular sex differences, which include genetics and hormones.

When it comes to participation in organ donations, researchers noted that women are more often donors than recipients, while the opposite is true for men. This finding may indicate a sex difference in the incidence of medical conditions that require transplantation.

Northwell Health

Living and deceased donors

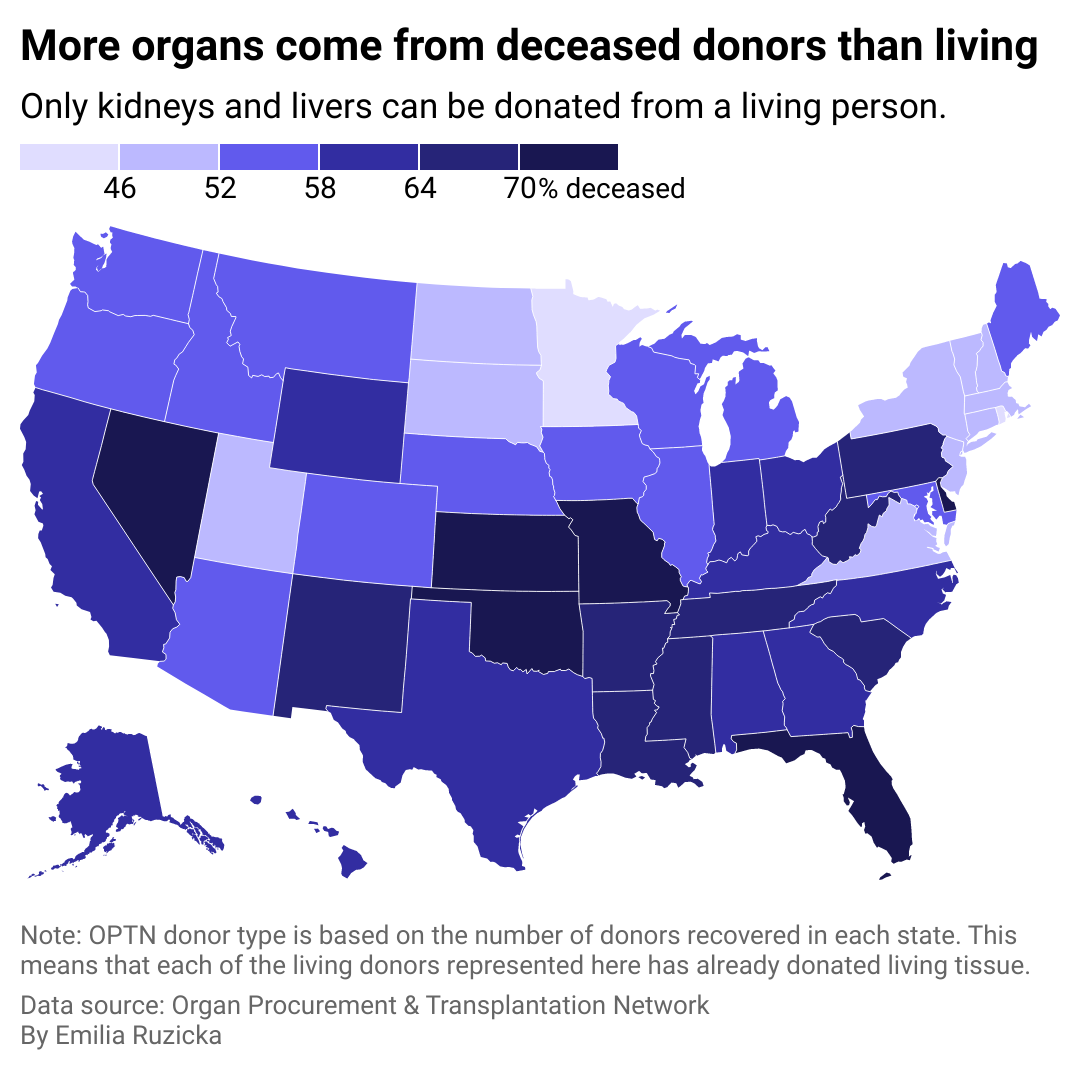

A map of the U.S. showing that more organs come from deceased donors than living donors.

Minnesota and Rhode Island are outliers in the U.S., with just 41% of donors deceased and about 59% living. Due to the nature of organ donation, far more organs are eligible to be donated from a deceased donor, while living donors can only give their kidney or parts of their lung, liver, and pancreas.

The first living donor kidney transplant was attempted in 1953 when a 16-year-old boy received a kidney transplant from his mother; however, the boy died weeks later. The first long-term success came in 1954 when a man received a kidney from his twin and went on to live for eight years. Living donor liver transplants were first successful in 1989, a decade after the first successful deceased donor liver transplant, while the first successful living donor lung transplant occurred in 1990.

Since then, the number of living organ donor transplants have steadily increased as scientific and technological advancements have continually improved surgical techniques, recovery for both patient and donor, and organ matching. By 2001, the total number of living organ donors outpaced that of deceased donors for the first time. The pandemic caused a significant plummet in living donor procedures but by 2021, surgeries grew 14% compared to 2020, with more than 6,500 living donor surgeries performed.

Northwell Health

Donor age

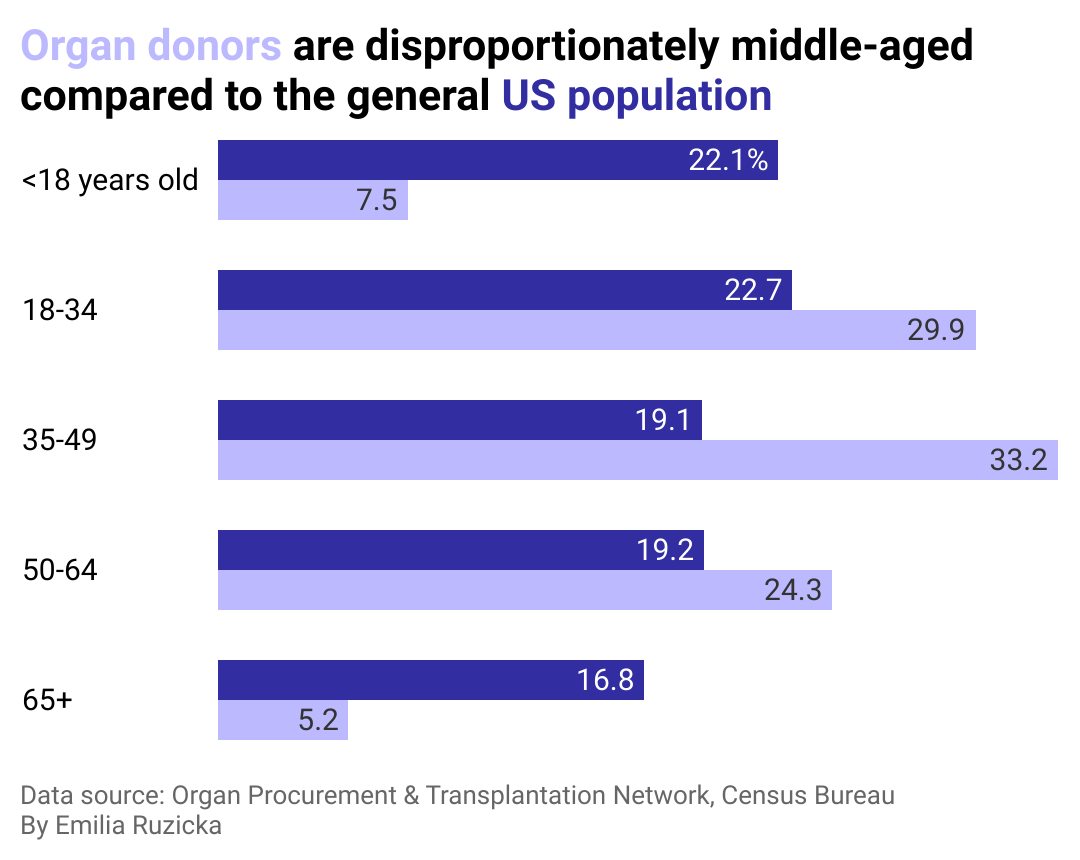

A grouped bar chart showing that the vast majority of organ donors in the U.S. are between the ages of 18 and 64 with a third being 35-49.

There is no age limit for organ donation, though older living donors should take extra precautions when considering the risks of surgery combined with any additional health concerns.

Donors under 18 must receive consent from a parent or guardian in most states, even if the child has indicated they want to be an organ donor on their driver’s license. Though very young children can be organ donors, most children who donate organs are between 11 and 17 years old.

Northwell Health

Donor race

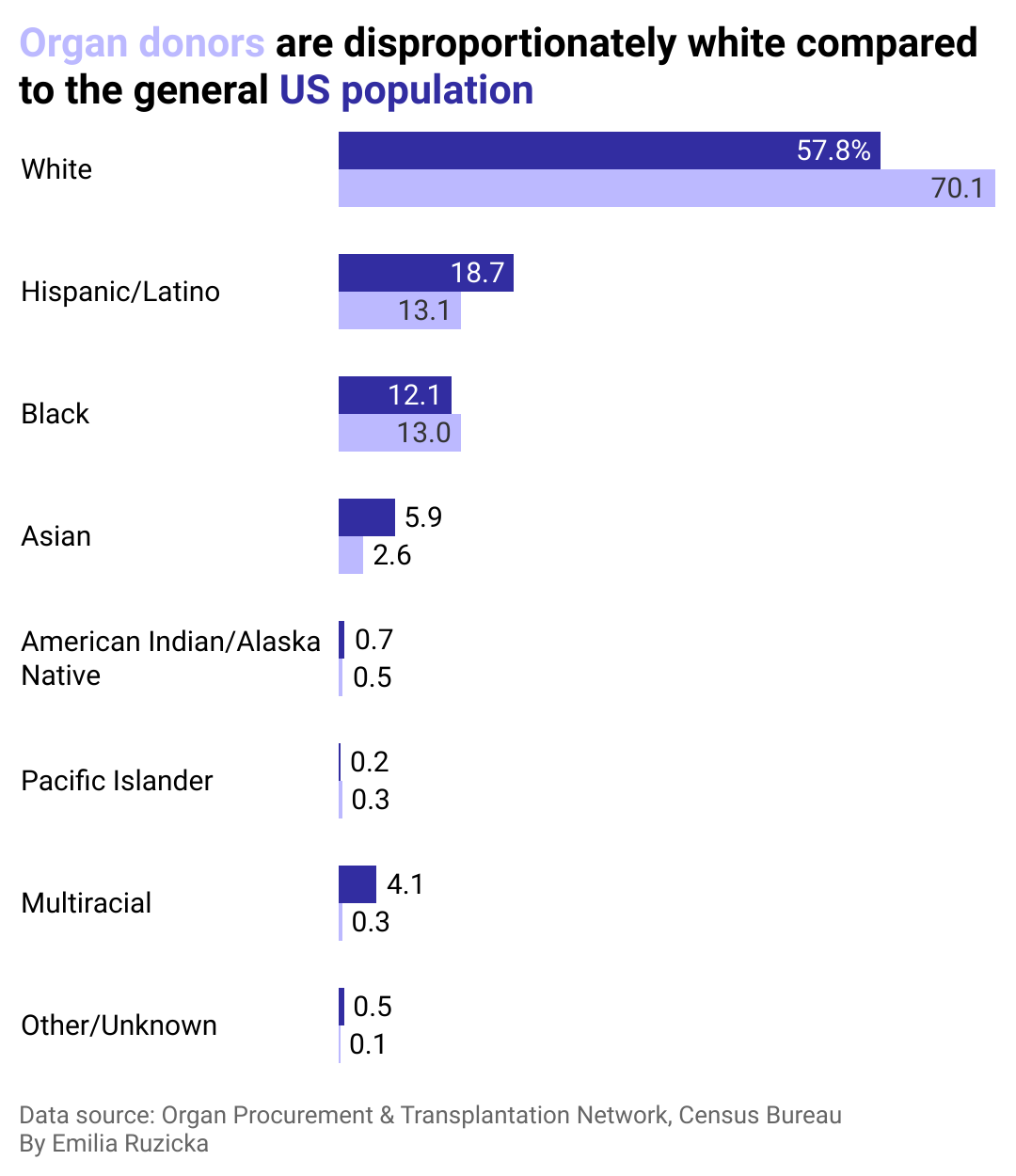

A grouped bar chart showing that organ donors are disproportionately white compared to the U.S. population. About 58% of people in the U.S. are white while about 70% of organ donors are white.

A 2006 study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that when randomly surveying participants in Ohio, Black people expressed a much greater sense of mistrust in the health care system and medical community, with some believing that being an organ donor would make doctors less motivated to save their lives in the event of a medical emergency. This mistrust comes from centuries of racial bias and wrongdoing against communities of color in the medical field.

While organ donors are more likely to be white, 60% of people on a transplant waitlist are people of color. This fact may be partly due to a higher instance of conditions leading to organ failure, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes in communities of color.

Factors such as religious beliefs, cultural traditions, and language barriers are also obstacles that continue to impact when, how, and from whom people of various races seek health care.

Many organizations who hope to promote organ donor awareness have recognized the gaps that exist in these communities and have suggested steps for health care providers to better understand and address mistrust. Using techniques that have led to successful public awareness campaigns, organizations recommend health care providers to study and better understanding the roots of mistrust within a community and take steps to repair them by being “culturally humble,” as well as reflecting on their own implicit biases.

National observances are another way to rally attention, and efforts to focus on more inclusion include National Minority Donor Awareness Month in August and National Donor Sabbath in November.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.