Black people spend longer in the hospital after giving birth. Here's why

Canva

Black people spend longer in the hospital after giving birth. Here’s why

A pregnant person lying in a hospital bed cradling her stomach.

Healthy labor and delivery outcomes focus not only on the baby but on birthing people, and those outcomes start at the hospital during and immediately after childbirth.

Most, more than 80%, of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable, “highlighting the need for quality improvement initiatives in states, hospitals, and communities that ensure all people who are pregnant or postpartum get the right care at the right time,” said Wanda Barfield, M.D., M.P.H., director of CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health at the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, in the report.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to examine data from the Department of Health and Human Services to see which states have the most significant disparities in length of pregnancy-related hospital stays for Black people.

Pregnant Black people are three times more likely than pregnant white people to die from a pregnancy-related complication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s a result of underlying inequities, medical experts say.

“Obviously death is the worst possible outcome, but there are a lot of things that happen along that continuum that can really impact women’s lives and have severe consequences in their health for the long term,” said Dr. S. Michelle Ogunwole, assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, who researches racial disparities in health outcomes among Black Americans who are pregnant or have given birth.

Pregnant Black people experience severe maternal morbidity, or unexpected negative outcomes during labor and delivery resulting in serious short- or long-term health issues, at higher rates than pregnant white, Hispanic, and Asian people.

For instance, Black people are more likely to give birth by cesarean section, which is major abdominal surgery. Between 2019 and 2021, 36.2% of pregnant Black people gave birth by C-section, compared to 30% of pregnant white people and 29% of pregnant people of American Indian and Alaska Native descent, according to National Center for Health Statistics data compiled by the March of Dimes.

After an uncomplicated C-section, patients routinely stay in the hospital three to four days, compared to people who deliver vaginally and routinely stay one to two days in the hospital, said Dr. Dawnette Lewis, director of Northwell’s Center for Maternal Health.

In addition, Lewis said that the patient may have a pre-existing medical condition requiring a more extended stay at the hospital. She also suggested longer stays may occur because some new parents may want to learn how to care for their babies or work with a lactation consultant.

Dr. Amanda P. Williams, who is the clinical innovation advisor for the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, said doctors may keep people in the hospital longer after giving birth if they aren’t able to return to a medical facility for follow-up care due to childcare, transportation, or a lack of available appointments.

“When you have a patient with preeclampsia or a similar complication, you want them to be seen again within the first week of delivery,” Williams explained.

![]()

Northwell Health

How some states are working to close the gap

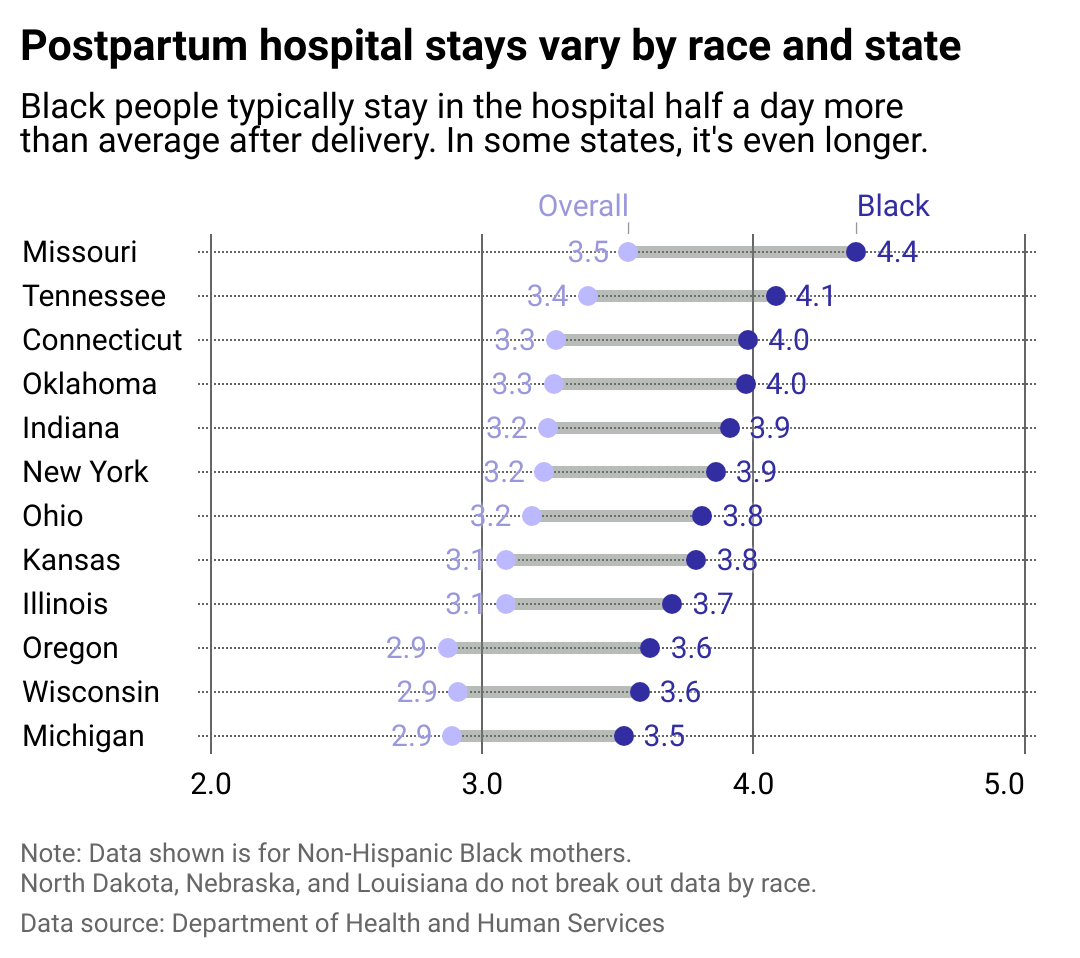

A line chart shows how postpartum hospital stays vary by race and state.

The average length hospital stay for a person who has just given birth is 3.1 days, but for Black people, it’s 3.7 days, or about 14 hours longer. The data represents all delivery outcomes—including vaginal and cesarian births as well as abortions and stillbirths. Missouri has the longest average additional stay, of 20 hours.

The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services studied post-pregnancy health outcomes and found that mirroring national numbers, compared with their white counterparts, Black Missourans who have given birth are three times more likely to die in the following year, according to their 2023 report looking at 2018 to 2020.

As a result of the findings, the state expanded Medicaid coverage for people who have given birth for one year after delivery; funded an effort to improve care for pregnant people, people who have recently given birth, and newborns; and funded an overall expansion of Medicaid eligibility.

Monkey Business Images // Shutterstock

Risk factors for pregnant Black people

New parents smiling, holding their baby in the hospital.

Despite spending the most money per capital for health care in the world, the U.S. has the “highest infant [and] maternal mortality rates,” according to the American Journal of Managed Care.

However, pregnancy care experts warn that news articles and studies can make it appear that the inequity Black people face during pregnancy is because of “individual behaviors or socioeconomic conditions” and erroneously adopt “narratives of personal responsibility and blame,” according to a 2021 paper by founder and president of the National Birth Equity Collaborative, Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, and several colleagues.

Rather, the paper calls for the health care industry and provider community to “define the root causes of health inequities” and “identify the structural determinant of maternal health inequities and recommend policies to address them.”

Black birthing people are more likely to experience postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia, two of the leading causes of pregnancy-related death during and in the week after giving birth, according to the March of Dimes. The paper recommends several concrete steps to improve information tracking and actual care standards for pregnant people, those in active labor, and those who have recently given birth.

Editor’s note: Stacker recognizes the language used to talk about gender has shifted to meet the understanding that gender is a spectrum. In this article, we have used gender-neutral terms when possible, as not all pregnant people identify as “mothers” or “women.” We use gendered language in the case of direct quotations and in the characterization of data to stay true to how sources collected and presented the information.

Story editing by Kelly Glass and Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.