Most common settings for foodborne outbreaks in the US

SURKED // Shutterstock

Most common settings for foodborne outbreaks in the US

A waitress working in restaurant.

In 2018, more than 600 people who visited a Chipotle in Powell, Ohio, to grab a bite got an extra surprise with their meal: diarrhea and stomach cramps.

Their symptoms, according to the Food and Drug Administration, were related to the bacteria Clostridium perfringens, which grows rapidly in food not stored at appropriate temperatures. Three years prior, 141 people reported sickness following a “norovirus incident” at a Boston location of the fast-casual Mexican chain, which was likely the “result of an ill employee who was ordered to continue working after vomiting inside the restaurant,” according to a Department of Justice press release. The American-based restaurant chain agreed to pay a $25 million criminal fine and launch a food safety program to resolve the charges it faced.

Those Chipotle customers aren’t alone, as foodborne illnesses are more common than expected. About 1 in 6 Americans get sick from foodborne illness every year, according to the CDC. Of those 48 million people, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die

Local and state health departments play a major role in outbreak prevention in the United States. Numerous municipalities and counties deploy inspectors to retail food establishments to create publicly available reports about the location’s sanitary conditions. The more infractions the inspector finds, the lower the resulting score. Infractions are often weighted on their severity or likelihood of causing foodborne illnesses.

In Los Angeles County, for instance, food kept at the wrong temperature would cost four points; however, a more minor violation (like an employee leaving their coffee cup near a food-preparation area) would only cost one, according to a 2023 Los Angeles Times article. If the infraction is severe enough—like a restaurant operating without running water—an inspector might shut it down on the spot.

How restaurant grading systems effect change

While Los Angeles restaurant managers must post their letter grades on the establishment’s front window, the grading system varies nationwide. Columbus, Ohio, uses a color-coded system (a yellow sign may cause patrons to pause and consider eating elsewhere); King County, which encompasses Seattle, uses emojis in a bid to make it easier for immigrants to understand the restaurant’s rating. Many health departments post their reports on their websites detailing each violation for patrons wanting to know how a restaurant’s score was calculated.

The grading systems and the public pressure they put on restaurant operators seem effective. In the year following the program’s implementation, there was a 13% decrease in hospitalizations due to foodborne disease in Los Angeles County, according to one study published in the Journal of Environmental Health.

While various common types of restaurants and high-traffic catered events collectively lead the way in reported foodborne illness outbreaks, any food preparation settings can act as a conduit for stomach cramps (or worse) too.

To that end, FoodReady used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to explore the most common settings for causing foodborne illnesses in the U.S. from 2009 to 2021. For some of these incidents tracked, multiple settings are listed. The “major setting,” or most common location, is used in those cases. It can be hard to track down the exact origin of foodborne outbreaks; as a result, 11.8% of incidents did not have specific settings listed.

![]()

FoodReady

Restaurants lead the way

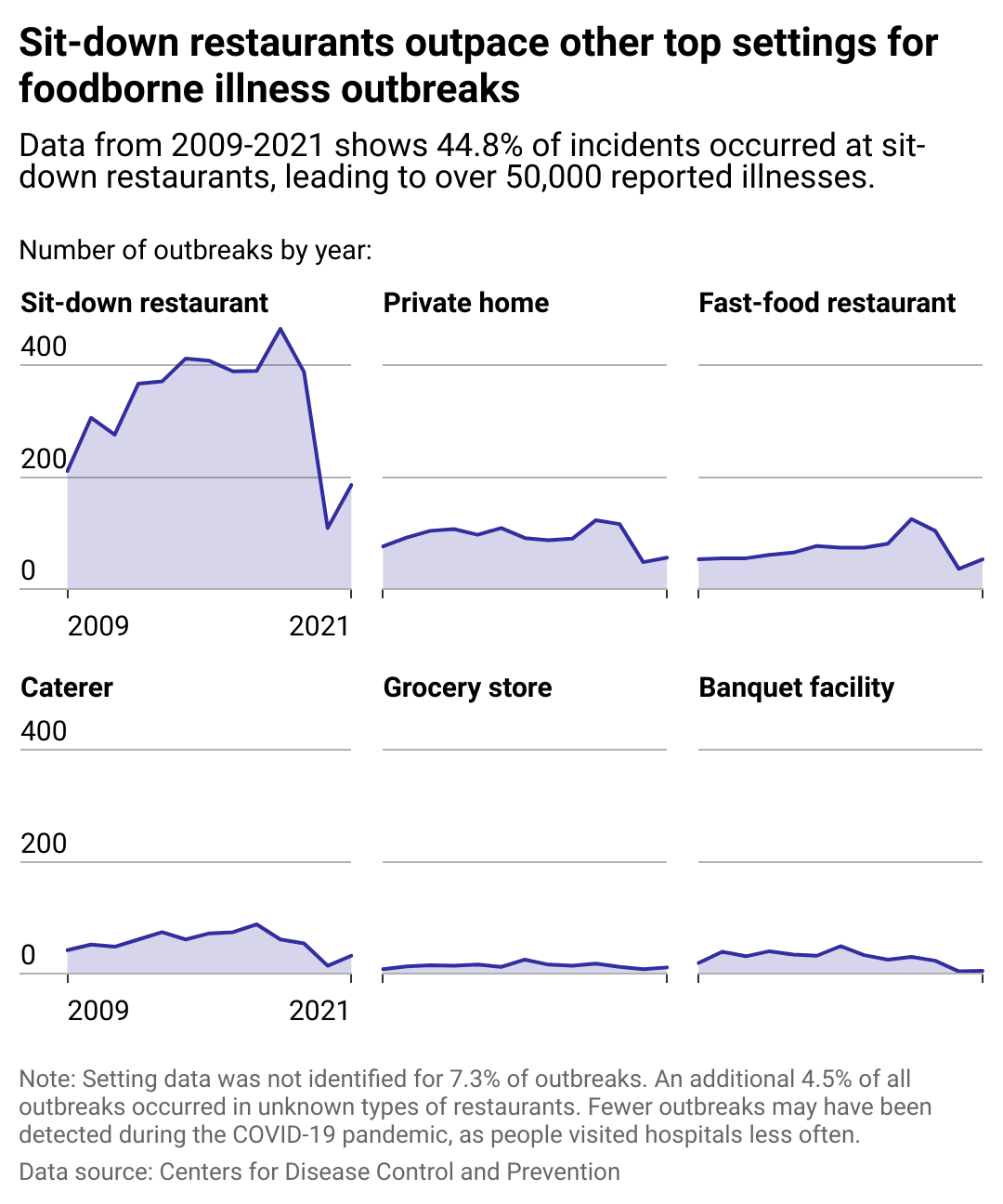

Multiple line charts showing sit-down restaurants outpace other top settings for foodborne illness outbreaks. Data from 2009-2021 shows 44.8% of incidents occurred in sit-down restaurants, leading to over 50,000 reported illnesses.

In retail food settings (restaurants and caterers), the CDC found that about 2 in 5 foodborne illness outbreaks could be traced back to sick or infectious workers contaminating the food.

The CDC highlighted common-sense measures to help mitigate potential outbreaks, like creating policies that workers must report cold, flu, and other related contagious disease symptoms (such as vomiting, diarrhea, fever, etc.) to their manager. Companies should subsequently provide paid sick leave to keep sick workers out of the kitchen, and workers must consistently wash their hands and wear gloves while handling food. The CDC also found that restaurants with Certified Kitchen Managers were less tied to foodborne outbreaks.

However, the exact details of outbreaks can be difficult for officials to track down. When an E. Coli outbreak was connected to several Wendy’s locations in August 2022, public health officials interviewed 67 of the 97 customers reportedly affected, asking for a “detailed food history.” They found that 4 in 5 of those interviewed had eaten at a Wendy’s in the week before reporting symptoms. However, according to a CNN report, they struggled to pinpoint which ingredient caused the outbreak.

“Many of them ate burgers and sandwiches with romaine lettuce, but the specific ingredient that caused the outbreak could not be confirmed,” a CDC investigation notice said.

In instances where a specific ingredient can be traced, government agencies or manufacturers may institute a recall. To see recent recalls and learn about safe food preparation, visit FoodSafety.gov.

dotshock // Shutterstock

#10. Buffet restaurants

People dishing from buffet.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 107 (1.1% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 1,084 (0.7%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 49 (0.5%)

Monkey Business Images // Shutterstock

#9. Schools or colleges

Primary school kids eat lunch in school cafeteria.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 108 (1.1% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 4,764 (2.9%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 95 (0.9%)

sukiyaki // Shutterstock

#8. Long-term care facilities

Senior woman in wheelchair and her caregiver.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 109 (1.1% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 2,572 (1.6%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 143 (1.3%)

Frame Stock Footage // Shutterstock

#7. Prisons or jails

Prison tray of food passed through metal bars.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 124 (1.3% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 8,231 (5.0%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 93 (0.9%)

New Africa // Shutterstock

#6. Grocery stores

Woman taking packed pork meat from shelf in supermarket.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 182 (1.9% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 2,651 (1.6%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 259 (2.4%)

MNStudio // Shutterstock

#5. Banquet facilities

Banquet waiter carrying tray with food.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 364 (3.8% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 10,694 (6.5%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 111 (1.0%)

LElik83 // Shutterstock

#4. Caterers

Catering spread across table.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 733 (7.7% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 19,981 (12.2%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 378 (3.5%)

Kondor83 // Shutterstock

#3. Fast-food restaurants

Kitchen of a fast food restaurant.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 913 (9.6% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 14,867 (9.1%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 1,431 (13.3%)

Ingrid Balabanova // Shutterstock

#2. Private homes

Pile of dirty dishes in a kitchen.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 1,196 (12.5% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 18,761 (11.4%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 2,655 (24.6%)

Serghei Starus // Shutterstock

#1. Sit-down restaurants

A dirty restaurant industrial kitchen.

– Outbreaks reported, 2009-2021: 4,278 (44.8% of all incidents)

– Illnesses reported: 50,737 (30.9%)

– Hospitalizations reported: 2,184 (20.2%)

Story editing by Elsie Drexler. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Clarese Moller.

This story originally appeared on FoodReady and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.