This year, investment in rural votes isn't just at the top of the ticket

Moab Republic // Shutterstock

This year, investment in rural votes isn’t just at the top of the ticket

An election polling station with a “Vote Here”/”Vote Aqui” sign.

With the 2024 presidential election just days away, Democrats and Republicans in rural areas are directing their focus beyond the top of the ticket and toward state and local-level offices. So-called “down-ballot” races feature candidates for state legislature, city council, local school boards, and even judges and police commissioners. These elected officials decide on issues in their community, such as education, housing services, public transportation, and health care.

Thus far in 2024, 75% of these down-ballot elections were uncontested nationwide, meaning a candidate ran for office without opposition. This trend is common in rural America’s red districts, according to Contest Every Race, a group that tracks races where Democrats do not put up a nominee. The group said one reason Republicans run unopposed in red districts is because Democrats have historically felt their odds are so slim it’s simply not worth it to campaign.

However, this year’s presidential election has directed fresh attention to districts where down-ballot candidates have historically run unopposed, The Daily Yonder reports.

Lauren Gepford, vice president and executive director of Contest Every Race, said down-ballot races are important for Democrats this year, given how disengaged many voters are with politics.

“Politics isn’t just about whatever’s on CNN or Fox News or MSNBC, but it really is about the policies that affect your local life,” Gepford said. Contest Every Race told the Daily Yonder they are funding grassroots organizing partners in 292 rural counties this year as part of their rural grants program for Democrats to contest races in rural communities where Republicans would otherwise run unopposed.

Bill Greener is a Republican strategist based in North Carolina. In an interview with the Daily Yonder, he said this is an election where every vote—from rural to urban—matters.

“This is an election of ‘leave no vote behind,'” Greener said.

Looking at the top of the ticket, two vice presidential candidates claiming rural roots means both Democrats and Republicans are overtly vying for rural voters’ support in November. But for both parties, the strategy goes beyond campaigning for the White House.

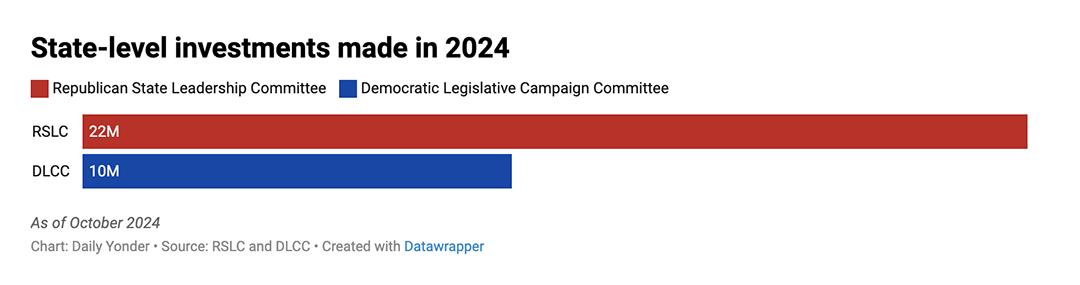

At the state level, the Republican State Leadership Committee, or RSLC, has invested over $22 million across 21 states as of September 2024. Total investments from the RSLC top $34 million for the election cycle, and include distributions in swing states like Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

The Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, or DLCC, the RSLC’s counterpart, told the Daily Yonder it has made $10 million in state-level investments this year. The investments have gone to the DLCC’s target states, which include (but aren’t exclusive to) swing states like Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. This comes after Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign announced it would transfer an additional $2.5 million to the DLCC as part of its strategy to support down-ballot candidates.

For Republicans, Greener said these investments are aimed at earning more votes in rural areas.

“Our money goes there—to rural areas—to drive up the margin,” Greener said.

The story in rural areas is more complicated for Democrats. Rural organizers in places like Missouri, said that funding for down-ballot races historically has not come from the national Democratic party.

Jessica Piper ran for state representative as a Democrat in Nottoway County, Missouri, in 2022. She lost after receiving 25% of the vote. Then she joined Blue Missouri, an organization that provides crowdfunding for under-funded Democratic nominees in some of the reddest and most rural districts in the state. These districts, according to Piper, have often been neglected by investment from the national Democratic party. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, she said.

“Don’t give us any money, don’t invest in us, and look what happens,” Piper said.

![]()

The Daily Yonder

Democrats Build a Bench in Rural Areas

Chart showing state-level investments made in 2024.

The strategy in Missouri is changing this year, Piper said. Money—to the tune of $100,000—has come in from the Democratic National Committee.

“It’s going to take a while before we see the fruits of our labor,” Piper said. “We know it’s a long game, but we know it’s worth playing.”

Other Democratic rural organizers hold a similar sentiment to Piper’s, regardless of whether they have also received national party funding this year.

In upstate New York, Paolo Cremidis runs the Outrun Coalition, a grassroots group of 523 local Democratic elected officials from across rural America. Cremidis, the coalition’s executive director, said each official also brings a diverse identity not often represented in politics, including women, immigrants, young people, Latinos, Indigenous people, people of color, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

“We need to delve into this diversity, because if we don’t, we are not going to have a candidate base or bench going into the future,” Cremidis said. Much like building a team of players, Cremidis and other rural organizers are looking to field a group of candidates they can train and then tap to run in future races.

Building a bench of Democratic candidates in rural areas is part of what Piper called a “long game” for Democrats. Gepford said Contest Every Race has similar goals with its recruitment efforts, which focus on races at the local and state level.

Republicans Look Beyond Rural

As Republicans outspend Democrats on down-ballot races by more than two to one, they are looking beyond rural America to pick up voters.

This is part of the national strategy, said Nicholas Jacobs, a professor of political science at Colby College and author of The Rural Voter: The Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America.

Jacobs said former President Donald Trump needs to win in more districts than he did in 2020 in order to win the presidency. For the Republican candidate, Jacobs said there are more votes to be won in the suburbs.

“Even if you start to lose a little bit in rural areas, if you can pick up in suburban areas, then you do just that,” Jacobs said.

Greener said turnout can actually be a challenge for Republicans in rural areas.

“There are a whole lot of people that don’t turn out and vote in rural America,” Greener said. For elected offices down the ballot, community turnout decides the fate of local candidates.

Additionally, Jacobs said local candidates are not immune to the hyper-polarization and partisanship happening on the national scale this election cycle

“It is becoming harder and harder for candidates running down-ballot to escape the nationalized images of the party,” Jacobs said.

Some Democrats, though, have maintained a degree of separation. Gepford said this is the “reverse coattails” effect.

“Our [Democratic] candidates down-ballot will outperform the presidential [race], because they’re more likable in the area than the presidential candidate is,” Gepford said. Contest Every Race is focused on identifying reverse coattails in rural counties, particularly in swing states, this year.

That is, if rural Americans vote. Even as vice presidential candidates JD Vance and Tim Walz bring up their connections to small-town America while on the campaign trail—the word “rural” was used multiple times during the vice presidential debate, after no mention at all during the presidential debate—rural strategists and organizers from both parties said it remains to be seen how community members will cast their support this year, if at all.

In some rural areas, Jacobs said local candidates could push people to cast ballots more than anything else.

“Sometimes local candidates’ ground games, especially for state legislative office, do actually have an important bearing on who turns out, so it’ll be interesting to see,” Jacobs said.

This story was produced by The Daily Yonder and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.