Stories behind the Trail of Tears for every state it passed through

Ed Lallo // Getty Images

Stories behind the Trail of Tears for every state it passed through

Young man nuzzling up to his horse in open field while reenacting the Trail of Tears journey in 1988.

Markers and remnants of the Trail of Tears stretch as a series of scars across the American landscape. The trail’s facilitators stand as a representation of America at its worst; its captives a mark of stunning resiliency in the face of indescribable cruelty and terror.

Despite massive encroachment by white settlers on North American lands throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the sovereign Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations in the early 1800s accounted for significant swaths of land stretching from northwest Georgia into Alabama, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

The Cherokee were particularly adept at pursuing signed documentation protecting their native lands; a dozen treaties were signed between the United States federal government and the Cherokee between 1785 and 1819.

As white settlers continued advancing on Native American lands, tribes sought mitigation in Washington courts to little or no avail. Gradually, other major tribes throughout the young United States acquiesced with treaties that forced their migration west to the other side of the Mississippi River.

Gold was discovered in Georgia in 1828; by 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. The law granted the president the authority to offer Indigenous groups, numbering around 125,000 people at the time, 16,000 acres west of the Mississippi River in Oklahoma Territory in exchange for tribal lands within state boundaries. The removal of these Indigenous groups would free up millions of acres across the American Southeast for mineral extraction, cotton farming, and the growing white population.

The Indian Removal Act had an immediate effect: Many groups moved west beginning in the early 1830s, following roads and rivers out to “Indian Territory” in present-day Oklahoma. The Trail of Tears is the shorthand used for the series of forced displacements of more than 60,000 Indigenous people of the five tribes between 1830 and 1850 and extending up through the 1870s.

The Choctaw Nation’s forced removal began in 1831; Seminoles in 1832; Creek in 1834; Chickasaw in 1837; and the Cherokee in 1838—the largest forced removal of all. Illini Confederation, Osage, and Quapaw tribes were also displaced.

Stacker compiled a list of stories behind the Trail of Tears for each of the nine states it passed through, based on archived personal accounts and historical records and largely focusing on the most significant removal—that of the Cherokee—in 1838 and 1839. Much of the history has been lost due to the destruction of Indigenous lands and settlements following the forced removal of these people from their homes and, later, structured education systems that did not acknowledge these individuals, their languages, or their histories.

During the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, tribal communities numbering in excess of 17,000 (16,000 of whom were Cherokee) were met by more than 7,000 troops deployed by President Martin Van Buren. Homes were looted, people were rounded up in camps, others were killed, and thousands at a time were marched west, often at gunpoint. Routes—not one but a tangle of trails—forced people from North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, Alabama, Arkansas, and Illinois to Oklahoma by foot, train, and boat.

The main route stretched from nearby present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, through Nashville and Clarksville then through Hopkinsville, Kentucky, into Illinois via an Ohio River crossing, then on to “Indian Territory” in present-day Oklahoma. Along the way, a lack of food, horses, supplies, and other provisions—including shoes for many travelers—made the trek challenging for all and impossible for thousands. Deaths accumulated quickly due to severe exposure, famine, and contagious diseases such as cholera, influenza, malaria, measles, dysentery, syphilis, tuberculosis, typhus, whooping cough, and yellow fever.

Those who survived the march were met in Indian Territory with insufficient supplies necessary for survival and a harsh landscape inhospitable to hunting, farming, or gathering. In total, between 1830 and 1850, roughly 100,000 Indigenous people east of the Mississippi River were relocated against their will to Indian Territory.

More than 4,000 people died along the way, representing as many as 1 in 4 Cherokee. Survivors remade the Cherokee Nation, which exists today as a still-sovereign nation based out of Oklahoma with more than 450,000 citizens across the world.

The Trail of Tears was designated by Congress in 1987 as a national historic trail. Keep reading to discover numerous stories and significant markers along the trail.

![]()

starryvoyage // Shutterstock

North Carolina

A wooden Nation Park Service sign for the Qualla Indian Reservation.

Western North Carolina’s mountains stood as the centerpiece of Cherokee civilization long before the arrival of Europeans. Valleys within the Hiwassee, Little Tennessee, Tuckasegee, and other rivers served as ideal farming communities for the Cherokee.

Around 3,500 Cherokee were living in North Carolina at the time of the Trail of Tears. As government officials estimated headcounts and assessed roadways for the forced removal of Indigenous communities, the Unicoi Turnpike (now a historic trail) was selected as the main route, as it ran through northern Georgia into western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

The Old Army Road between Andrews and Robbinsville was expanded in just 10 days in the spring of 1838 to accommodate wagons and the thousands of travelers who would be coming by foot.

As the vast majority of Cherokee were rounded up, held in internment camps, and then marched from their homes across multiple states, a small group stayed hidden in the Appalachian Mountains in North Carolina. These Cherokee eventually earned the right to stay and their rights were recognized. Today, that group is known as the Oconaluftee Cherokee.

RodClementPhotography // Shutterstock

Georgia

Sunset on Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site, an open field with a mound and a wooden staircase/ramp leading up to it.

As cultures blended in the early 19th century, a number of Cherokee assimilated into the white settler culture: putting up English-style housing, adopting white settler farming techniques, and in some cases establishing plantations.

Georgia, in 1802, became the last colony to cede its western land to the United States government. The Cherokee maintained the occupation of their lands that were promised by treaty—but white residents in the state were increasingly unhappy that Cherokee communities could continue to govern themselves and maintain rights to land that settlers sought to occupy.

The state passed legislation in 1828 nullifying all Cherokee Nation laws; and in 1829, when gold was found on Cherokee land in Georgia, pressure mounted on the government to remove the Indigenous communities entirely. This pressure came at the same time President Andrew Jackson was actively destroying land titles and treaties with the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

When the Trail of Tears commenced, all properties owned by Cherokee were forfeited. Today, numerous Georgia historic sites—from the Cedartown Cherokee Removal Camp and New Echota State Historic Site to the Funk Heritage Center and Etowah Indian Mounds State Historic Site (pictured)—commemorate this period in American and Indigenous history.

Nicholas Lamontanaro // Shutterstock

Tennessee

A downward view of the water steps.

Roughly 2,800 people spread across three detachments traveled by a mix of steamboats, keelboats, and towing flatboats, down the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, White, and Arkansas rivers from present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Fort Coffee, Oklahoma. The first detachment, which included as many as 800 people, departed on June 6, 1838.

The river routes along the Trail of Tears were not much safer than land trails, as the rations and supplies were equally as scarce and the elements just as brutal. The first detachment made it from Chattanooga to Fort Coffee within two weeks. Another detachment traversed the Arkansas River during an extreme drought that made boat passage impossible and forced the travelers to finish the journey by foot in extreme heat.

More than 70 people died during the nearly two-month trek. Later passages were even more dangerous with some death tolls estimated as high as 2,000.

[Pictured: A view of The Passage (aka The Water Steps) at Ross’s Landing Riverfront Park in Chattanooga.]

Katssoup // Shutterstock

Alabama

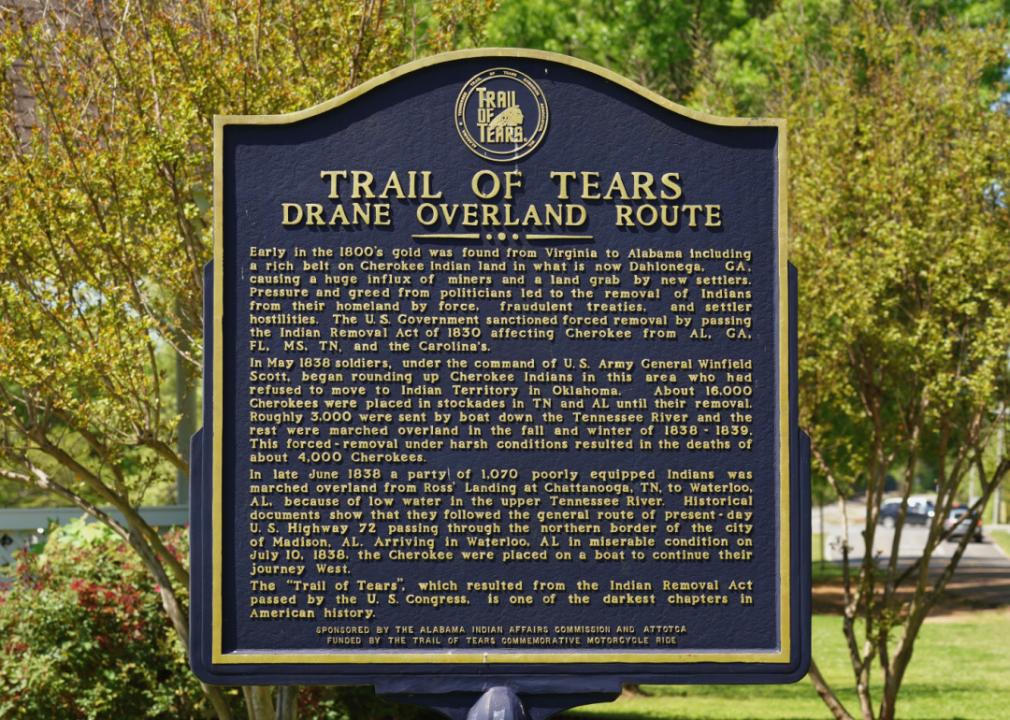

A placard of the Trail of Tears Drane Overland Route.

About a quarter of the Cherokee Nation in the 1820s lived in present-day Cherokee, Etowah, and DeKalb counties in Alabama. Cherokee living in northern Alabama at the time were part of the sovereign Cherokee Nation headquartered in New Echota.

When the May 1838 deadline arrived for Native communities to leave on their own accord, eight companies of the U.S. Army marched into northeast Alabama along with militia from Alabama and Tennessee to remove Cherokee and Creek communities by force. Posts and stockades in forts Payne, Lovell, Likens, and Turkeytown were built to house the troops, store supplies, and imprison Indigenous communities—including roughly 16,000 Cherokee—before the trek began toward Indian Territory in October 1838.

Major Trail of Tears locations in Alabama include Waterloo Landing, Tuscumbia Landing, and Little River Canyon Center.

Waterloo Landing, where a historical marker stands citing its significance, was the last point of departure for Indigenous people from the South and earned the location its nickname as the “End of the Trail.” An annual event at the site memorializes the Trail of Tears and the perseverance of the Indigenous community.

Numerous Indigenous individuals and families were transported to Tuscumbia Landing by train for transport to Oklahoma. People in the Little River region were rounded up and marched along the Trail of Tears’ Benge Route, so-named for John Benge, who led the detachment of soldiers leading the march.

At Lake Guntersville State Park, the Trail of Tears is remembered annually with storytelling, a variety of ritual dances, memorial walks, and displays. Blevins Gap Preserve is home to the Smokerise Trail, where visitors can retrace more than a mile of the Trail of Tears.

[Pictured: A Trail of Tears historical marker in Madison, Alabama.]

Canva

Arkansas

A leaf-covered trail runs through a thick autumnal forest.

Hundreds of miles of the Trail of Tears winds through Arkansas. The state is distinct in that each of the land and river routes passed through it, bearing witness to all five of the southeastern tribes that were forcibly removed.

Today, five Arkansas State Parks sit along these routes: Lake Dardanelle, Mount Nebo, Petit Jean, Pinnacle Mountain, and Village Creek. The largest unbroken section of the trail can be found in Village Creek State Park in Wynne; from Mount Nebo, visitors can see sections of the Arkansas River all five tribes were transported across.

Ivan Dmitri/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Kentucky

A view of the Ohio River from afar.

The Cherokee crossed into southern Illinois from Kentucky via the Ohio River in present-day Smithland.

More than 1,700 Cherokee from the Peter Hildebrand Detachment were forced to spend two weeks camped out in the Mantle Rock area in Kentucky in the middle of winter while waiting for the Ohio River to thaw for water passage to Illinois.

When passage became possible, the travelers were required to pay $1 each for a ferry ride that typically charged 12.5 cents for the passage of a wagon. That winter, Berry’s Ferry made more than $10,000 on the backs of the Indigenous people who were forced to surrender their homes.

eurobanks // Shutterstock

Missouri

A sign for the Trail of Tears State Park.

The water route of the Trail of Tears passes through southeastern Missouri along the Mississippi River; the state is also home to three removal land routes, the Benge, Hildebrand, and Northern.

The routes passed through parts of present-day Missouri counties Barry, Bollinger, Butler, Cape Girardeau, Christian, Crawford, Dent, Green, Iron, Laclede, Madison, Ozark, Phelps, Pulaski, Reynolds, Ripley, Saint Francois, Scott, Stone, Texas, Wayne, Webster, Wright, and Washington. All the land routes go through present-day Mark Twain National Forest.

Numerous historic sites in Missouri commemorate this voyage, including the Trail of Tears State Park in Jackson, the Snelson-Brinker House in Steelville, and the Star City Ranch trail segment in Barry County.

Canva

Illinois

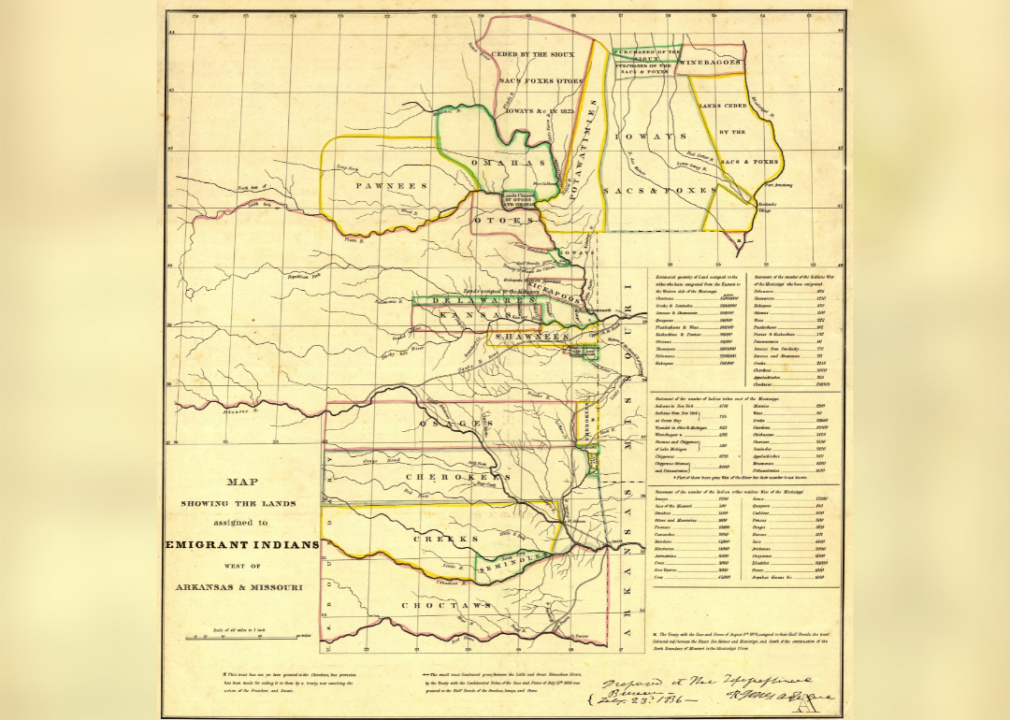

A paper map from 1836 showing the Indian Territories.

It was early December 1838 when five detachments of Cherokee arrived in Golconda, Illinois, a city founded almost 23 years prior in the southern part of the state.

Illinois represented the most difficult passage of the trail, with frigid temperatures that brought rain and snow. It took three months for more than 15,000 Cherokee to make the 60-mile journey across the state whereas a previous group took a week. The Mississippi River’s banks were frozen, with large chunks of ice visible and audible as they crashed their way downstream. Travelers were restricted by many landowners from camping or building fires to stay warm or prepare hot food.

Paths stretched east to west between the Ohio River at Golconda to the Mississippi River just west of present-day Ware, along sections of today’s State Highway 146 and various rural roadways. Other lengths of the trail in the state have been lost and overtaken by forest.

While staying in Golconda after crossing the Ohio River, several Cherokee were murdered by local white residents who then sued the federal government for $35 per Cherokee burial. They lost the suit and abandoned the bodies in shallow, unmarked graves near present-day Brownfield. Today, a Trail of Tears monument marks the site.

By mid-December 1838, Cherokee travelers were stuck in the present-day Trail of Tears State Forest waiting for the floating ice in the Mississippi River to melt. During that wait, some people were sold into slavery. A small number escaped. Many succumbed to the elements and died.

[Pictured: An 1836 map showing the Indian Territories (now Oklahoma) assigned to displaced Eastern Indian tribes.]

RaksyBH // Shutterstock

Oklahoma

A red flag with an emblem in the middle reading Seal of the Cherokee Nation, Sept. 6, 1939, flies in the wind in front of a blue sky.

Throughout the 1830s, as thousands of people arrived in the Oklahoma Territory, communities began adapting to the new surroundings, forging new relationships, and reestablishing a government that was modeled after the United States. The Cherokee tribal headquarters remain in present-day Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

In the last 200 years alone, Cherokee who resettled in Oklahoma have endured countless additional hardships: from missionaries who frequented Indian Territory as early as the 1820s to save Indigenous souls; to the Civil War and Reconstruction, which further impeded the Cherokee’s newly resettled land; to the Dawes Act of 1887; and the Great Depression in the 1930s. By 1970, the western Cherokee had lost more than 19 million acres of land in Oklahoma.