Deschutes County has already set a record for drug overdose deaths this year, at 27 – but there’s also some signs of hope

Emergency Dept. visits for opioid overdoses have dropped since August, locally and statewide

BEND, Ore. (KTVZ) – Deschutes County isn’t just on track to set a record for drug overdose deaths this year – it’s already there, with 27 reported in 2024, primarily due to the deadly opioid fentanyl, often combined in even more fatal fashion with methamphetamine use.

That was one of the disturbing aspects of the stat, graph and map-filled update county commissioners received Wednesday morning on what the agenda billed as an “update on Oregon’s drug overdose mortality crisis.”

But county Public Health Epidemiologist Mathew Christensen also had some more positive (or less negative) news to share in his talk, the presentation of which you can review below.

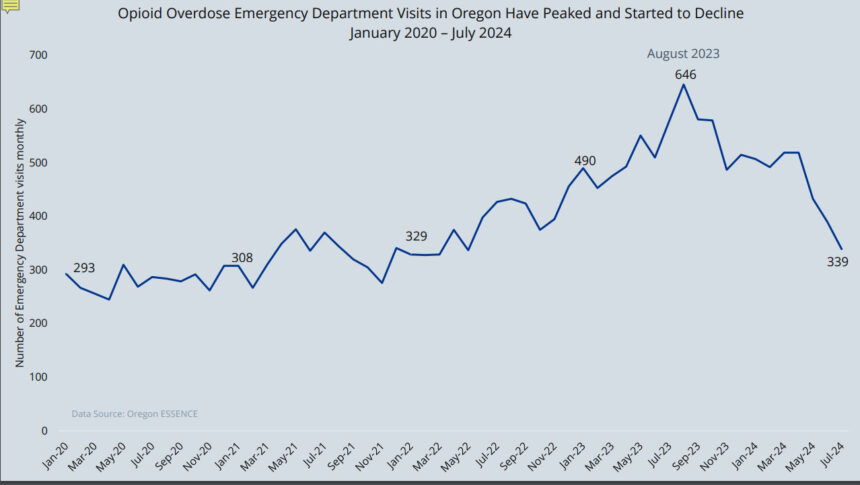

There are signs both statewide and locally that since last summer, fewer people experiencing drug overdoses are showing up at hospital emergency departments, after a surge reflecting the West Coast arrival of fentanyl in recent years.

Every stat has a lot of caveats – for example, Christensen noted that every effort is made to count only unintentional (accidental) drug overdoses – not suicides. Another example: Commissioner Phil Chng asked if these deaths are counted in the county where they occur, or where the person lives (the latter – it’s resident data).

There’s also a focus on comparing rates per 100,000 residents, not raw numbers, since smaller counties would always fare better. And Oregon saw a surge in recent years to nearly 40 overdose deaths per 100,000 residents, “some of the highest rates in the nation,” Christensen said.

While other drugs, such as purloined prescription medicine, can play a role in many deaths, Christensen told the board that “fentanyl is the most lethal and the strongest force … and it does drive up overdose deaths,” since it hit the West Coast in 2019-2020.

Last year’s rate map shows the worst problems are west of the Cascades, from the Portland area to Lane County and southern Oregon. And even with Deschutes County’s record 27 drug overdose deaths so far this year – one more than in 2022, while last year dropped to 24 - the rate per 100,000 would remain comparatively low, at about 13.

Nearly half of Oregon’s fatal drug overdoses last year involved a combination of fentanyl and meth, he said.

But Christensen later shared more with us later about the “very positive news” that hospital ED visits for opioid overdoses – the people who survived – hit its high point for the last five years last August - and that from that point forward, “we have a pretty steep drop over the next 12 months.”

“It’s an undeniable fact that something has changed,” he told us – adding quickly that they don’t yet know why. He expects those data reports in the next year or so, and while he tries not to speculate too much, he has some ideas about why.

So if the summer of 2023 was indeed the peak in this tragic statistic, Christensen said, “what might happen in 2024 is that we might not see another large increase, that we have seen the past four years.”

He’s confident about the welcome decline, noting that it’s evidence not just the Oregon hospital ED admissions but the latest national overdose death data, which began dropping in the last four months of 2023.

Fewer overdoses could be related to a variety of factors, such as the more prevalent accessibility of Narcan, which can reverse ODs, but Christen seen he believes “something is happening to fentanyl” itself.

He noted that fentanyl’s source chemicals generally come from China, arriving in large quantities on container ships in Mexico, where they are turned into the deadly pills that come across the border.

Could it be that the drug is less potent – less deadly than before? Or that the more recent stepped-up efforts at addiction treatment is having the desired impact? Perhaps, but there could even be some political aspects that have begun to restrict the supply or nature of the chemicals that go into fentanyl.

Christensen doesn’t claim to know – not yet, anyway. But he pointed out that President Biden last year began to put pressure on Chinse Premier Xi Jinping, who “agreed to clamp down on (fentanyl) distributors in his country.”

“If they can slow that down, no one in the pipeline can do” much if anything to make up for it -- and that, he said, could be affecting the fentanyl pills hitting our streets.

But it's not better news about all drug overdoses: hospital Emergency Department visits for meth and stimulant-related overdoses have not declined recently, as opioid-related ODs have.

Asked about that whole question of "why" regarding fewer people suffering opioid overdoses showing up at hospitals, Lt. Mike Landolt of the Central Oregon Drug Enforcement Team said he has no idea if what Christensen suggested about China's chemicals or other efforts is true or not.

"I can tell you fentanyl seizures locally continue to be on the rise," Landolt said.