A new malaria vaccine could save millions, but more still needs to be done to stop the deadly disease

Photo Illustration by Michael Flocker // Stacker // Shutterstock

A new malaria vaccine could save millions, but more still needs to be done to stop the deadly disease

A hypodermic needle is held in front of a magnifying glass looking at mosquitoes.

A new vaccine for malaria may reduce malaria cases by 77%, according to clinical trials, but significant challenges remain when it comes to fully eradicating the disease. The new vaccine, R21/Matrix-M, is a three-dose regimen that was endorsed by the World Health Organization in September 2023.

Prior to this endorsement, the only existing malaria vaccine, RTS,S/AS01, reduced malaria episodes by 40% with a four-dose regimen. This advancement was nevertheless a breakthrough in the prevention of the mosquito-borne disease, which is complicated by the insects’ rapid life cycle and the nature of the human immune response to parasites.

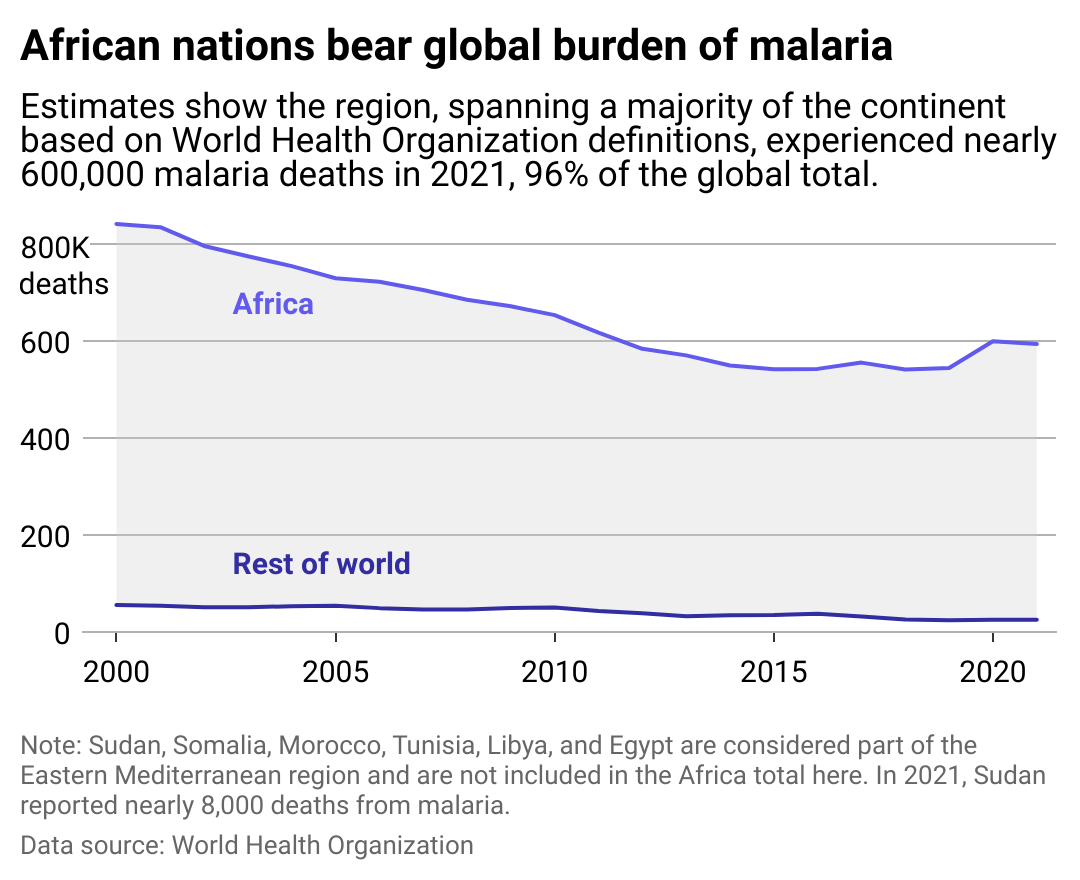

Still, these vaccines have yet to significantly reduce the prevalence of one of the global leading causes of child fatalities. In fact, the mosquito-borne illness causes over 600,000 deaths each year, about 95% of which occur in the WHO African Region comprising 47 member-states in Africa, according to the organization’s 2022 World Malaria Report.

Moreover, vaccine distribution is just one step in the process of full inoculation, a process that requires a minimum of three dosages administered four weeks apart. This is especially challenging for regions where malaria is most rampant because many of them do not have particularly advanced infrastructure for providing health care. According to a 2021 report by the Africa Health Agenda International Conference, only 48% of people in Africa received the health care they needed. The region also has a ratio of just 1.55 health care workers per 1,000 people, far below the WHO’s standard of 4.45 health workers per 1,000 people needed for sufficient health care services.

To explore these issues further, Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to explore the global burden of malaria using WHO data and the challenges to ending the disease, even as multiple vaccines enter the market.

![]()

Northwell Health

Most malaria deaths are in Africa

Line chart showing African nations bear global burden of malaria based on annual deaths from the disease. Estimates show the region, spanning the majority of the continent based on WHO definitions, experienced nearly 600,000 malaria deaths in 2021, 96% of the global total.

Multiple factors make Africa significantly more vulnerable to malaria spread than other continents. Africa has the fastest-growing population of all continents, and much of the population is highly mobile in part because of a 2016 decision by the 55-nation African Union to facilitate intracontinental migration. Human mobility is a significant factor in disease transmission, a pattern observed across other major health crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

The consequences of climate change are also fostering malaria cases. Malaria-carrying insects thrive in warm environments with high rainfall, and precipitation is directly linked with malaria outbreaks in areas where the disease exists, according to a 2011 study by scholars in Germany and Ghana. Additionally, researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center determined that malaria-carrying mosquitoes are now reaching areas of the continent that were previously too cold, including southern regions and higher elevations, based on data spanning the past 120 years.

Further, the most lethal malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is the most prevalent in the African region. The species is becoming increasingly less detectable in rapid diagnostic tests and gaining resistance to artemisinins, drugs that are commonly used to treat drug-resistant malaria. The continent faces increasing amounts of insecticide resistance among its mosquito populations in general. For example, in a 2020 study led by the Oxford Big Data Institute, researchers determined that in 2005, 15% of West Africa had mosquitoes that were unaffected by deltamethrin, the insecticide used in treated bed nets. But by 2017, almost all of West Africa—98% of it—had deltamethrin-resistant mosquitoes.

This trend was also observed in other malaria interventions such as indoor residual spraying, which uses pyrethroids—another insecticide to which malaria-carrying mosquitoes are increasingly developing resistance.

Northwell Health

Efforts to tackle the disease in the most at-risk countries

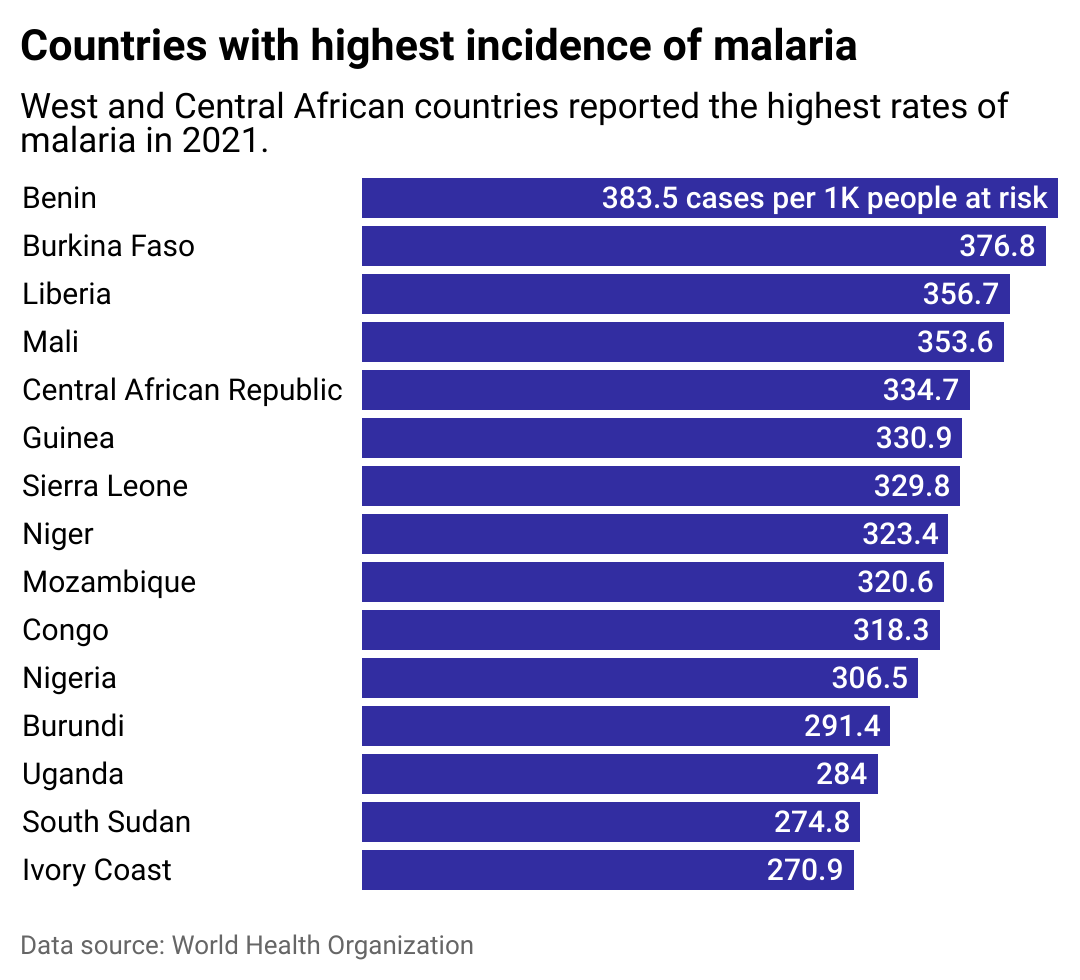

Bar chart showing countries with highest incidence of Malaria, including Benin, Burkina Faso, and Liberia. West and Central African countries reported the highest rates of malaria in 2021.

The emergence of the newest vaccine is expected to compensate for supply shortage issues that affected the rollout of the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine. WHO, in partnership with UNICEF and Gavi, intends to allocate 18 million doses to 12 African countries between 2023 and 2025. However, the global demand for malaria vaccines—costing an estimated $8 per dose—is expected to reach 40 million to 60 million doses by 2026.

Many countries with the greatest need for vaccines, however, are also short of money: For example, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are within the top four countries with the highest deaths from malaria, as well as within the top 10 poorest countries in the world.

Efforts to curb malaria spread are not limited to vaccination-related initiatives. One focus is directed at curbing the spread of artemisinin-resistant parasites to avoid further limiting the applications of the treatment, while other researchers are attempting to develop alternatives. However, to date, the only African countries to be declared malaria-free by the WHO are Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritius.

Story editing by Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.