How Fetterman flipped Pennsylvania

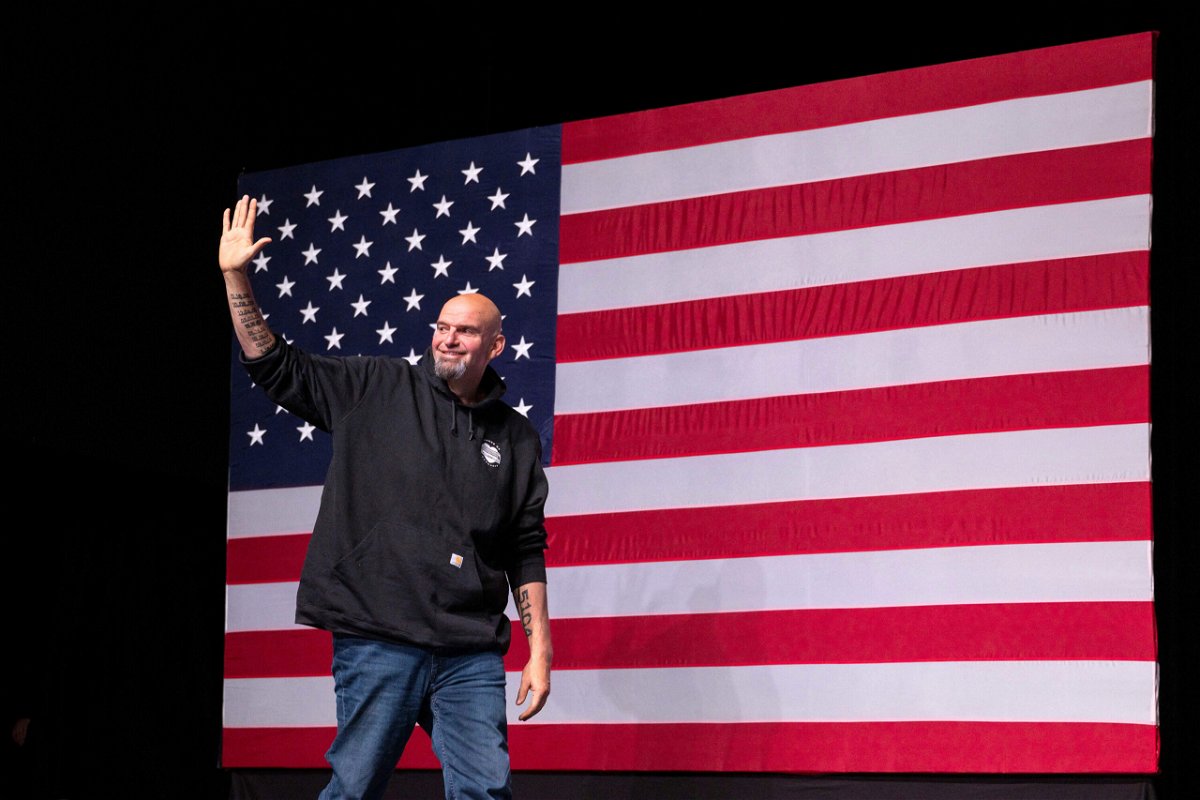

John Fetterman waves as he arrives onstage at a watch party during the midterm elections in Pittsburgh

By Dan Merica and Gregory Krieg, CNN

When John Fetterman’s team told him he was going to be Pennsylvania’s next senator late into Election Night, the Democrat laughed. He smirked. Then, struck by the emotional end of a campaign that included a near-fatal stroke just five months ago, Fetterman wept.

Soon, he was standing up in front of the microphones as supporters chanted his name, nodding his head as if in disbelief. Hand over his heart, he looked out and saw his slogan on signs in the crowd: “Every county, every vote.”

“And that’s exactly what happened,” Fetterman said, alluding to his campaign’s plan to narrow losing margins in rural counties while winning the suburbs and running up the score in urban Democratic strongholds. “We jammed. Them. Up.”

Fetterman’s victory over Republican Mehmet Oz, the cardiothoracic surgeon turned TV doctor and former President Donald Trump’s chosen candidate, flipped a seat the GOP had held for more than a decade and narrowed Republicans’ path to reclaiming the Senate majority. It was also the culmination of Fetterman’s own political journey, from big, brash small town mayor in Western Pennsylvania — an idiosyncratic character that, even a decade ago, drew national curiosity — to the cusp of membership in one of the country’s most traditionally genteel political institutions.

For Fetterman’s top aides, some of whom had been working with him since his failed 2016 Senate primary bid, the understanding that victory was nearing built like a “slow crescendo,” campaign manager Brendan McPhillips said. In the campaign boiler room, the legacy of bad Democratic election nights’ past fed into an air of overriding caution.

But the dam burst when returns from Erie, a swing county in the state’s northwest corner, showed Fetterman with a nearly double-digit lead.

Because it was unclear at the time, at little before midnight, when the race would be called, McPhillips, who first worked with the Democrat in 2015, told the candidate, “John, you are probably not going to get your blue check for a few days, but you are going to be the next senator.”

Then the first news outlets began calling the race for the Fetterman, the climax to a campaign that saw his stroke, a painful public recovery and bore the hopes of Democrats across the country.

How the race was won — and lost

For Rebecca Katz, the campaign’s top adviser, and McPhillips, this was their second go-round with Fetterman in a Senate campaign. Katz first met him in 2015 ahead of the 2016 primary, when he finished a distant third behind Katie McGinty and Joe Sestak with less than 20% of the vote.

“We can’t tell the story of John Fetterman as a US Senate nominee without talking about the origin story, in terms of what happened in 2015 and how we tapped into some real grassroots enthusiasm,” Katz said. “But we didn’t have the money to win the race.”

That memory propelled now-Lt. Gov. Fetterman to formally kick off his campaign in February 2021 — giving him a headstart on what would be a diverse and crowded primary field.

Fetterman, without a patron or validator, delivered a resounding victory by winning all 67 counties, often by overwhelming margins what ended up being a four-candidate race. He even came away on top in Philadelphia, with nearly 37% of the vote. Fetterman also swept the collar counties around the city, which would become a key focus for him and his opponent in the fall, prevailing in each by an average of almost 25 percentage points.

But his triumph was tempered by a harsh new reality. On the Friday before the primary, Fetterman, who was feeling unwell but determined to attend a morning event, decided to go to the hospital at the insistence of his wife, Gisele Barreto Fetterman. The campaign went quiet for days before Fetterman revealed in a statement that he had suffered a stroke.

“I had a stroke that was caused by a clot from my heart being in an A-fib rhythm for too long,” he said. “I’m feeling much better, and the doctors tell me I didn’t suffer any cognitive damage. I’m well on my way to a full recovery.”

The following two months — which Fetterman spent much of at home recuperating — ended up being the most critical period of the Democrat’s campaign. Unable to do in-person events, the campaign leaned into a hyperactive social media presence, all directed at defining Oz as an out-of-state elitist by using a mix of memes, pithy tweets and, at times, the help of famous celebrities.

Their chosen labels, colored by buzzy stunts involving Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi from “Jersey Shore” and a series of self-owns by Oz — most memorably his odd effort to illustrate the effects of inflation by filming a video of him shopping for ingredients for a “crudité” at a supermarket, the name of which he bungled — ended up sticking.

“It wasn’t just sh*t-posting,” Katz said. “It was a strategic plan to define Oz early and define him as not being from PA or for PA.” Fetterman, she added, insisted the content never be “mean,” and often spent time during his recovery pinging staff with memes and ideas to connect with the voters with whom he couldn’t personally engage.

But the success of the messaging even surprised Fetterman’s top aides. The strategy caught on, drove media attention, and consistently put Oz on the defensive, forcing him to burnish his Pennsylvania roots in sometimes awkward ways.

“John was not on the trail. He was resting and recovering. But we couldn’t just surrender the summer,” said Joe Calvello, the campaign’s spokesperson. “It wasn’t going to break through if we talked about insert issue that plays well here. We had to define Oz.”

The stickiness of the attacks also struck Republicans.

“Oz emerged from the most brutal Republican primary in the country. He had high negatives, he had no money, and he had the capacity to self-fund, to get back on air and repair his image and chose not to,” said a top Republican strategist who worked on Senate races. “He had a Democratic opponent who was sidelined because of health issues. And he allowed months to go by — precious months — that could have been spent virtually unopposed repairing his image, not doing anything.”

Republicans quickly saw Fetterman’s caricature of Oz – especially the attacks that he wasn’t from Pennsylvania and couldn’t effectively represent it – resonating with voters, the operative said. The attacks began to create an image of the Republican as someone who would do anything to get elected, including move.

The strategy, and the tactics that delivered on it, was validated one last time on Election Day. In CNN’s exit poll of the race, 56% of voters said Oz had not lived in Pennsylvania long enough to effectively represent the state. Fetterman won that group by a margin of nearly 70 percentage points.

One the great ironies of Pennsylvania’s Senate contest, which commanded the most money and attention in the key period between Labor Day and Election Day, is that Republicans now believe Oz lost the election in those months Fetterman spent off the campaign trail.

“We defined (Oz) while he was off in Ireland or Palm Beach or wherever he went” after the primary, Katz said. “We did it while John was recovering from a stroke.”

Armed with an endorsement from Trump, Oz narrowly won his party’s nomination in May. But it was a close race that divided the party. Oz emerged victorious but damaged. He had little cash to work with, underwater approval numbers and scores of conservative Republican voters win over.

“Oz wouldn’t have won the primary without Trump. No question about that,” said Ryan Costello, a former Republican congressman from Pennsylvania.

But once clinched the nomination, Trump became less of a weapon than an albatross. Oz would not campaign with him again until the final weekend before Election Day.

The debate

Fetterman’s success over the summer gave him some breathing room, but his race with Oz — like many across the country — grew more competitive after Labor Day, as more voters tuned in to the race and tens of millions of dollars from outside groups like the GOP’s Senate Leadership Fund and others led to ads blanketing the airwaves.

Republicans began to find some success questioning whether Fetterman had been honest with voters about his health, noting that he never released full medical records and in increasingly blunt terms, pointing out the obvious: Fetterman often struggled to speak in public because of the lingering effects of his stroke.

Fetterman’s campaign insists he and his team were always straightforward and honest about what they knew about his condition and recovery. But the gravity of what Fetterman would later discuss on the campaign trail as a near-death experience took some time settle in. Katz, at home in New York when she got word of the stroke, immediately drove to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where Fetterman was hospitalized.

“I got there and it was just chaos. But the very first thing, when I finally did get to talk to a doctor, the very first thing they said to me was, John will make a full recovery from the stroke,” she recalled.

In the campaign’s statement days later, Fetterman said that the “campaign isn’t slowing down one bit.” It was true that top aides and staff went into overdrive, but the candidate would not return to the stump for nearly three months, when he rallied with supporters in Erie on August 13. But even then, with his recovery progressing, Fetterman’s ability to interact and communicate in crowded public settings was significantly compromised. Even direct conversations in any kind of dynamic environment were difficult.

To those aides who knew Fetterman well, just getting to the August event in Erie was a success.

“As someone who spent five days at the hospital in Lancaster, I was elated, I was crying,” Calvello said. “We looked at this like it was public recovery.”

But Fetterman’s cautious reemergence coincided with what multiple aides described as one of the more difficult periods of what had, up until the stroke been a smooth campaign. By mid-August, Fetterman’s rare appearances on the trail were met with new, well-funded frontside attacks from Oz, Republican groups and Fox News — the three simultaneously attacking the Democrat as a “far-left” radical with a “pro-criminal” agenda.

Fetterman aides knew that help was on the way in the form of October ad buys from big Democratic groups. But in the six weeks from mid-August to the end of September, Katz said, while many Democrats began to view his election as a shoo-in, the campaign began to see their internal polls tightening.

Questions about Fetterman’s heath, ranging from his fitness to serve in the Senate to, more immediately, whether he would debate Oz before Election Day soon dominated coverage of the campaign.

“It’s clear that he’s being dishonest,” Pat Toomey, the outgoing GOP senator, said of Fetterman at a press conference with Oz in early September. “He’s either not as well as he claims to be or he’s afraid to be called out for the radical policies he supports. It’s one or the other.”

So the campaign had a decision to make: debate Oz, and put Fetterman, who, even as his condition improved, struggled at times to speak fluently under any kind of duress, or refuse to share a stage with his opponent.

Fetterman struggled, as many expected, during what would be his lone one-on-one faceoff with Oz. He strained for words that never came, bungled lines he’d delivered hundreds of times without a second thought and seemed, to many anxious Democrats watching, to be failing at the most important goal: convincing swing voters that he was fit to competently do the job.

“We had seen him do better in prep. So, it was tough to see your friend and someone you care about struggle publicly in a forum we knew he was at a disadvantage, even without a stroke,” McPhillips said, admitting that “we were a little bit worried about how people would perceive it.”

But even as reviews of his performance rolled in, a mix of despair from the left and barely contained glee from the right, the Fetterman campaign was moving quickly to shift the narrative.

They seized, in particular, on one line from Oz, who opposes abortion rights but had sought to soften his position and said he wouldn’t support a federal ban on the procedure. That, Oz told voters, was in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s overturning Roe v. Wade.

“As a physician, I’ve been in the room when there’s some difficult conversations happening. I don’t want the federal government involved with that, at all,” Oz said when asked about the issue. But he didn’t stop there. “I want women, doctors, local political leaders, letting the democracy that’s always allowed our nation to thrive, to put the best ideas forward so states can decide for themselves,” Oz continued.

Before the night was out, Fetterman’s campaign had announced a new ad hammering Oz over his suggestion that “local political leaders” should have a hand, along with women and doctors, in the process.

Fetterman’s allies pounced, too. Ryan Boyer, the first Black leader of the Philadelphia Building & Construction Trades Council, called the Democrat’s performance “a profile in courage.”

Of Oz’s abortion remark, he quipped, “So now I want my local ward leader deciding something that’s going on with my daughter?”

Obama and Oprah

The final weeks of the campaign, which began a few days after the January 6, 2021, riot at the US Capitol, were a nerve-rattling, expensive whirlwind.

On Saturday, Fetterman appeared with former President Barack Obama for rallies in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, with President Joe Biden joining the Philadelphia event. It amounted to a welcome round of “solid” news cycles for a campaign in search of them, Calvello said.

But while aides enjoyed the adrenaline boost that Obama brought to the trail, they also pointed to a late endorsement — delivered with no warning, a few days before the presidential cavalry arrived — from Oprah Winfrey.

“We were getting ready for Obama and then Oprah endorsed,” Katz said. “And this was a devastating indictment of Oz’s career. The person who made him said she would’ve already voted for John Fetterman ‘for many reasons.'” So, they turned it into an ad.

Then the Democratic cavalry arrive in force. Fetterman, along with fellow Democrat Josh Shapiro, the state attorney general who led big from wire to wire over far-right Republican nominee Doug Mastriano in the race for governor, were joined by Obama and then Biden.

Just days later, Calvello watched silently as Fetterman took the stage on Election Night and immediately touted his campaign’s work in typically red enclaves.

Calvello remembered the turnout — and reaction — at a February event held at a wood-paneled fire station in Smethport, Pennsylvania (population: 1,436).

“Wherever people might feel they’ve been forgotten and marginalized … that’s where someone like me needs to be. Someplace like Smethport… these are places that should matter as much as anywhere,” Fetterman said, seeking to find common ground with the Northern Tier town.

The event had proven to Calvello that Fetterman could back up his somewhat audacious promise to cut, even slightly, into Republican control of rural Pennsylvania.

“Those were the words he always told me: ‘We are going to jam them up,'” Calvello said.

The same words — the specific phrase — he would use in his victory speech.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.