Workers are still experiencing burnout, so why aren't they using workplace mental health resources?

PeopleImages.com – Yuri A // Shutterstock

Workers are still experiencing burnout, so why aren’t they using workplace mental health resources?

A stressed woman at a desk.

Between mass layoffs, unaffordable child care, inflation, the COVID-19 pandemic, an always-on/available culture, and artificial intelligence replacing jobs, there are many valid reasons why more than half of Americans say they’ve felt burned out at work in the last year, according to a poll conducted by the National Alliance on Mental Illness in 2024.

Burnout is defined by the World Health Organization as a syndrome spurred by unmanaged, chronic workplace stress. Burnout researcher Christina Maslach says the main causes are varied, ranging from unsustainable workloads and feeling a lack of control to a lack of reward for one’s efforts and a disconnect between values and skills.

Symptoms of burnout include exhaustion, disengagement from the organization, and reduced effectiveness at work. In a study of more than 5,000 people published in Scientific Reports, researchers found that burnout can even devolve into larger health concerns like hypertension, high cholesterol, and other somatic diseases. For organizations, high employee stress levels can manifest in high absenteeism and turnover.

The pandemic spotlighted mental health issues and has caused more candid conversations in workplaces, yet not many workers are turning to their employer-provided benefits to reduce or prevent conditions like burnout.

In the American Psychological Association’s 2024 Work in America survey, a 23-year-old Asian male shared that “there can still be a stigma when it comes to mental health (especially when it comes to depression and anxiety). This can discourage people from seeking help in regard to their mental health.”

More than a third of workers worry that if they had to inform their employer of their mental health condition, they would be negatively impacted at work. These anxieties can be compounded, considering two-thirds of employees fear they will be laid off or their hours will be reduced, according to an Employee Benefits Research Institute report.

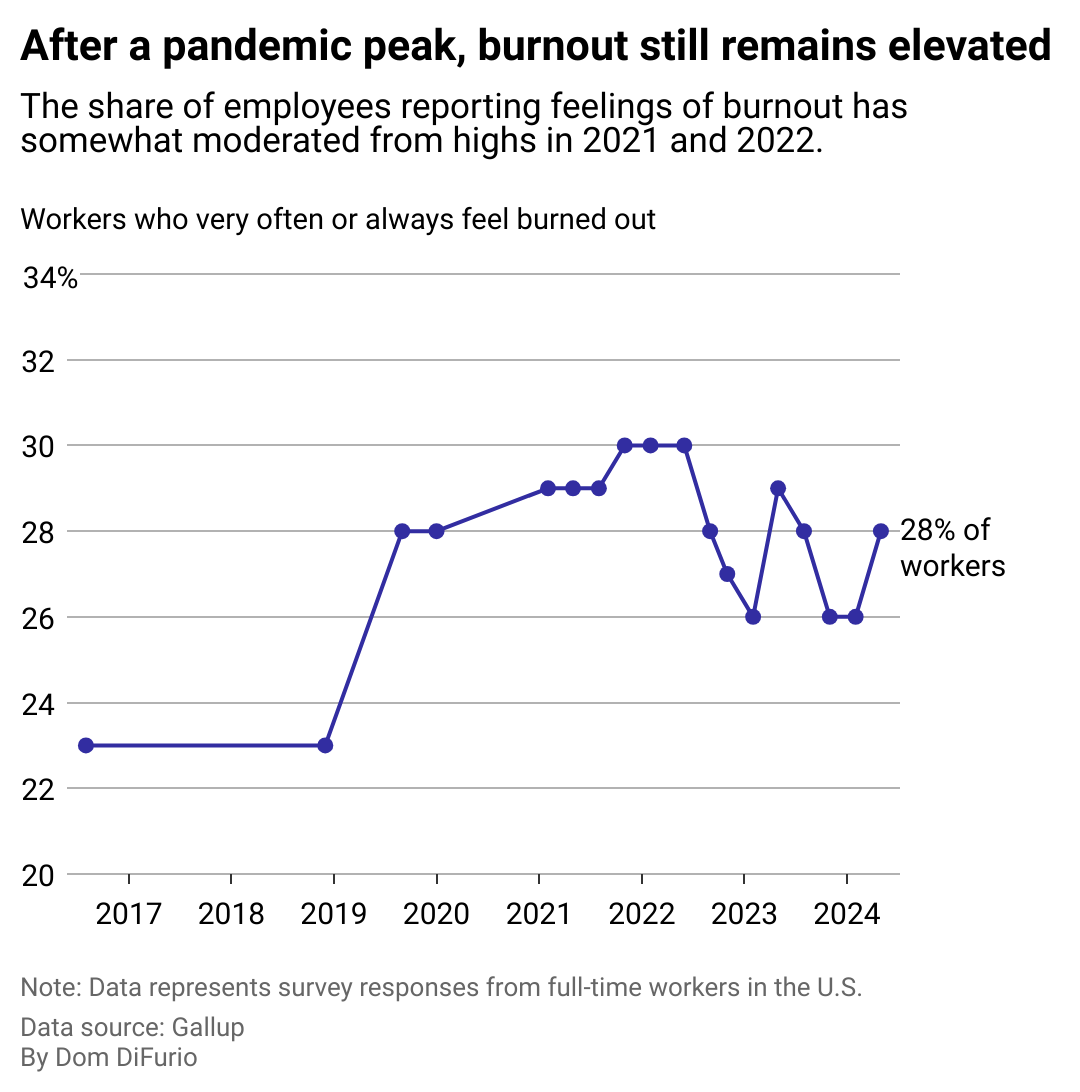

Wysa looked at Gallup data on burnout and survey data from the EBRI to illustrate the gap between who could benefit from workplace mental health resources and who uses them, as well as expert commentary on how employers can encourage uptake.

![]()

Wysa

Mental health services use declines despite increased importance to a burned-out workforce

A line chart showing the percentage of U.S. workers who responded that they are very often or always feeling burnout due to work, according to Gallup polling from 2016-2024. 28% of workers said they very often or always felt burnt out, down from a high of 30 in 2021 and 2022, but still up significantly from pre-pandemic levels when 23% reported the same.

Employees reporting feeling burned out have increased over eight years of Gallup surveys. Rates have remained inflated since the pandemic—now affecting 28% of workers surveyed in Gallup’s findings. In 2023, SHRM found that about half of workers were suffering, significantly more than Gallup’s research.

Stigma isn’t the only reason why American workers are not being proactive when facing burnout, though it contributes to 50% of workers not using their employee assistance program benefits for mental health, according to SHRM. Writing for Psychology Today, wellness expert Robyne Hanley-Dafoe and physiologist Greg Wells shared that employee perceptions around the effectiveness of these mental health programs through work and providers can also impact how much employees take advantage of these benefits. There may also be concerns about confidentiality, practical barriers to accessing services like long wait times, or simply a lack of awareness of the programs.

Fifty-two percent of employees surveyed by SHRM say they feel pressured to place the organization’s needs over their own to protect their jobs. Discounting one’s own needs for the good of one’s company was echoed in a survey response to Harvard Business Review‘s research: “I almost scheduled an appointment about a dozen times. But no, in the end, I never went. I just wasn’t sure if my problems were big enough to warrant help, and I didn’t want to take up someone else’s time unnecessarily.”

According to EBRI, just 66% are comfortable using benefits and services provided by their employer, even though employees recognized that mental health wellness programs are more important than they were last year.

These benefits can also be a key driver when choosing a new workplace, according to APA research. However, EBRI found that only 35% of Americans used the resources and tools from their employers last year to improve their mental health, down from 51% the previous year.

According to HR firms and psychologists, other factors—such as gender—could be at play for employees who aren’t using their mental health benefits. LinkedIn data shared with Fortune shows that 44% of females are experiencing burnout compared to 36% of males. Behavioral scientist Pam Cohen explained this to Forbes by noting women often feel like they must prove themselves consistently in male-dominated fields. Research published in the journal Review of Economics of the Household using more than 4,000 responses from 2002 and 2008 also suggests balancing company demands and unpaid work in the household for “traditional” women is also weighing on female employees. (“Progressive” women generally feel less burnout, according to the research).

Other demographics like cultural background, age, professional level, and the industry itself impact burnout, mental health issues, and the feeling of being psychologically safe enough to talk about these issues at work.

Canva

Getting more people to participate in mental health programs

Employees giving a group high five in a brightly lit office.

How employee-provided programs have traditionally addressed mental health issues through an individual lens may not cut it anymore, according to experts. Dr. Nigel Girgrah, chief wellness officer of Ochsner Health, told Newsweek that employee well-being needs to be treated with a larger-scale approach: “It’s not just building stronger canaries but redesigning the coal mine,” Girgrah said.

Based on years of studies about mental health in the workplace, nonprofit Mind Share Partners warned that employee wellness perks won’t suffice if their core needs aren’t being met by their employers. Writing for the Harvard Business Review, the organization suggested that going “back to basics“—like providing stable employment, a feeling of belonging, autonomy, and flexibility—is needed to make a difference in burnout.

Burnout demands a holistic framework for workers’ well-being, experts say. It involves looking at individual environments, encouragement from workplace leaders about accessing resources, and challenging the norms of success in the workplace. Trusted colleagues in the workplace can also normalize using mental health services by sharing how they used the benefits and the difference they made.

But participation in employer-provided programs has always been low—never more than 10% from the 1980s until now. This indicates that larger cultural changes need to be made to encourage more employees to take advantage of these benefits.

In a large, nationally representative study, research published in Review of Economics of the Household found that solutions to burnout should target perceived gender roles in society. Human resources experts also believe that rebranding these services can help remove the stigma of reaching out for help. Participation in T-Mobile’s employee assistance programs nearly doubled when services were no longer referred to as “EAP” and counselors were instead called “coaches.”

However, employers can only do so much. At some point, the key to change lies with the employees themselves. As Hanley-Dafoe wrote in Psychology Today: “Ultimately, you have bought your employees a great bed, but you can’t buy them a good night’s sleep.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on Wysa and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.