Concrete is one of the biggest contributors to carbon emissions: New technologies could change that

Canva

Concrete is one of the biggest contributors to carbon emissions: New technologies could change that

Close-up of concrete mixer truck pouring concrete into large basin.

Concrete is so ubiquitous that most of us don’t even notice it as we go about our daily lives. But look around and you’ll likely find it just about anywhere: It’s used to frame houses, pave driveways and walkways, repair dams and bridges, and in commercial building projects. It’s one of the most versatile inventions, but it’s also one of the most emissions-intensive materials used in construction.

Manufacturing a cubic yard of traditional concrete emits about 400 pounds of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that adds to the overall warming of the planet, according to the Portland Cement Association. Paving just a 20-by-20-foot driveway for two cars would use about 5 cubic yards, contributing emissions equivalent to the average home’s energy use for over a month.

Its environmental cost doesn’t have to be this high, though. Just as innovations like electric vehicles and solar panels have reduced emissions in the transportation and energy sectors, new technologies could accomplish the same goals for concrete. With the Inflation Reduction Act supporting green investments and technology in the U.S., Machinery Partner looked at solutions to roll out low-carbon concrete in both residential and large-scale settings.

The first thing to keep in mind is that concrete itself isn’t really the problem. It’s more due to the way it’s produced and its ingredients. Concrete is a mixture of water and sand or gravel mixed with a powdery cement product, most commonly a limestone-based type called Portland cement. Concrete’s inherent strength and availability in block, paver, and ready-mix pouring formats make it hard to replace.

But for companies and scientists trying to make low-carbon concrete, the key is slashing the percentage of carbon-intensive cement in the mix.

Cement’s emissions intensity comes from the high heat required to make it. Limestone is baked in a kiln reaching temperatures up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit to produce clinker, or compact balls of minerals. The clinker is later mixed with gypsum to form the raw material concrete companies need.

That process, according to a report from the Environmental Protection Agency, produces 1 metric ton of CO2 for every 1.3 metric tons of cement. Carbon dioxide is the most prominent greenhouse gas emitted into the atmosphere, and its heat-trapping power has accelerated global temperatures and climate change.

So it makes sense that the $300 billion Inflation Reduction Act, which passed a year ago and includes a focus on lowering carbon emissions, allocates at least $4 billion for acquiring and reimbursing green construction materials. The bill will also put nearly $6 billion toward grants and rebates to support retrofitting industrial and manufacturing facilities like cement plants.

Climate standards from the General Services Administration also outline requirements for buying clean construction materials for federal projects.

With the 2024 election looming, many in the green energy and construction space are aware of how quickly policy can shift. The challenge for producers is finding products that are lower in carbon while still being functional and profitable.

![]()

Bob Riha, Jr. // Getty Images

Lowering emissions and reusing waste

Dump trucks unload mining tailings.

At the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, scientists are exploring how to speed up mineralization, Earth’s natural way of capturing and storing CO2 in rocks. Many hope that along with renewable electricity, they can create a carbon-negative product that could be used in concrete.

The National Academy of Sciences estimates that 10 gigatons of CO2 would need to be sequestered annually for the next 30 years to meet climate goals. When contacted for this article, Kerry Rippy, a researcher at National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Building Technologies and Science Center, said that reformulating products like cement to capture CO2 could make a dent in that gigaton challenge.

The NREL’s research uses mining waste from one of research partner Newmont’s gold mines, offering the potential to divert byproducts, or “tailings,” from dams. It’s not market-ready yet, but producers using the technology could one day sell both the concrete to construction companies and the diverted emissions to businesses seeking carbon offsets.

“One of the exciting parts to me is that we’re not just sequestering carbon. We’re actually making valuable products that can be sold,” Rippy said.

Using mining waste in concrete mixes dates back to the Hoover Dam’s construction in 1929, but its popularity has been growing over the past 50 years. Traditionally, it’s been a supplement for cement, but with government support and companies setting their own net-zero goals, low-carbon concrete is becoming its own sector.

One company hoping to lead the charge is CarbonBuilt, which describes itself as an “ultra-low” carbon concrete company. By substituting Portland cement—the most commonly used cement worldwide that is a key ingredient to make concrete—for mining waste and using atmospheric CO2 to cure the final product, they say they can reduce emissions by 70% to 100% per concrete block.

The company has partnered with Blair Block in Alabama to manufacture concrete blocks used by a local masonry contractor in projects like a firehouse in Montgomery.

“Because we’re using these low-cost waste materials at the front end and the use of carbon dioxide and the other end is inexpensive and not capital intensive … it doesn’t force the producer to increase prices,” CarbonBuilt CEO Rahul Shendure explained.

Due to its weight, concrete is usually made locally, meaning manufacturers have to rely on smaller markets rather than shipping from far-off producers. To be competitive, low-carbon concrete costs need to stay close to market prices for traditional concrete. The potential to sell carbon credits also makes retrofits attractive.

CarbonBuilt largely relies on coal byproducts like fly ash, one of the most popular tailings used in concrete manufacturing.

Output from coal mining in the U.S. has fallen significantly over the past decade, but Shendure isn’t worried about relying on a shrinking industry’s leftovers. “Unfortunately, I think this material is going to be around longer than we probably want it to,” he said.

Nearly 70% of fly ash produced is now used according to the American Coal Ash Association. Up until 2015 over half of it went to waste, meaning millions of tons of it can be found in landfills and ash ponds.

Machinery Partner

Beyond the US

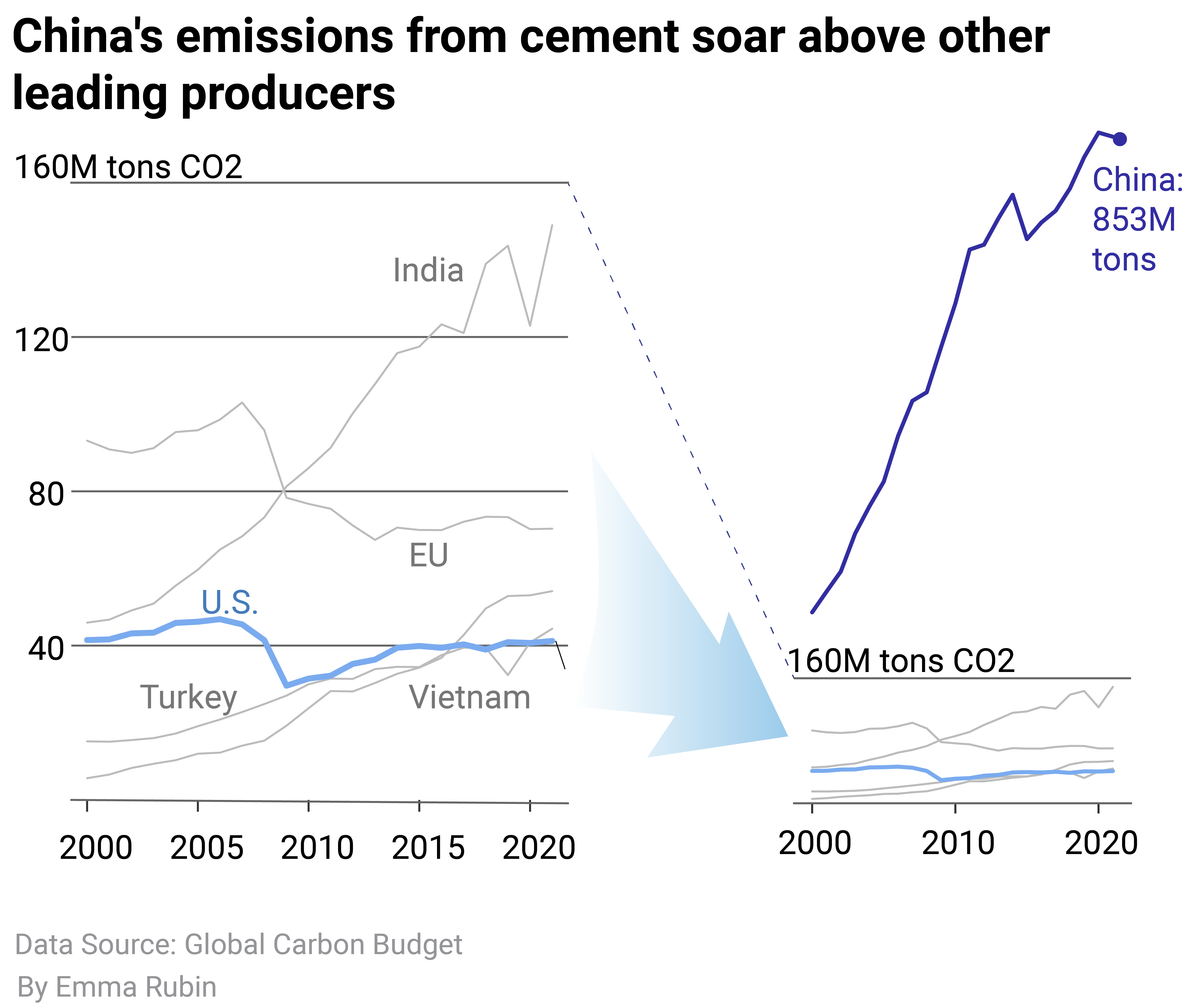

Line chart showing China produces 20 times more cement than the U.S., and production is continuing to grow.

Cement accounts for 8% of CO2 emissions on the global level. That’s more than the aviation industry, according to the International Energy Agency. But the statistic can be misleading: U.S. EPA data shows that the mineral industry, which cement is a part of, accounts for just under 2% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2021, emissions from cement production in China were more than 20 times those originating from the U.S. The International Energy Agency projects that global cement production will grow up to 23% by 2050, especially in regions with expanding infrastructure needs such as India and parts of Africa.

Even if the Inflation Reduction Act and market incentives support greener cement production in the U.S., solutions will need to be deployed globally to make a dent in worldwide emissions.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

This story originally appeared on Machinery Partner and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.